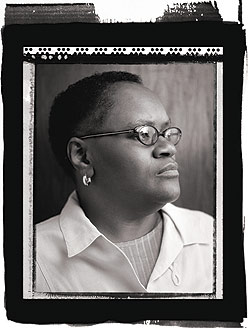

Martha Haley's book is filled with pictures of women she has met through her support group, Celebrating Life. Some, including those pictured above, are living with breast cancer. But dozens of others have lost their battle with the disease. "Each was a living person, a human being," she says.

Whenever breast cancer claims the life of another friend, Martha Haley inscribes the woman's name and date of passing in a special book of remembrance. Haley, who's waging her own tough fight against the disease, started compiling the book to honor the memory of women she came to know through Celebrating Life, the support group she founded a decade ago for African Americans who, like herself, have been diagnosed with breast cancer. The book is thick with photographs of the dead and with the poems and tributes Haley has composed to commemorate their lives. "I bonded with these women of color, and I watched them lose their battle," she says. "It's hard knowing and loving people and then saying goodbye."

Haley was just 36 when she learned she had an aggressive form of breast cancer that had invaded her lymph nodes. A teacher's aide living in South Chicago at the time and raising an 11-year-old daughter and two teenage sons, she endured the surgical removal of her right breast and intravenous blasts of chemotherapy that caused her hair to fall out. When she could find no breast cancer support group for African American women, she formed Celebrating Life and started holding meetings each month at Advocate Trinity Hospital, on Chicago's South Side. Through the group, she got an intimate glimpse into the disproportionate toll breast cancer takes on black women—in 2003, the mortality rate was 68 percent higher for African American women in Chicago than for white women, even though blacks were less likely to get the disease.

The women in the group who have died were mostly from the South and West sides of the city, many of them working-class, some without insurance. There are 75 enshrined in Haley's book—so far. "Each was a living person, a human being," she says. "These are mothers and sisters who have value in the community—mothers and sisters who make the community." Now 48, Haley knows that someday, maybe soon, her own name will be added to this heartbreaking ledger of the lost. Her cancer returned in 2000, costing her the other breast, and has since spread to her lungs. "My battle is winding down now," she says softly.

The book is many things—therapy for Haley, a repository of grief, a declaration of the dearness of life. But it is something more: an affront to basic ideals of fairness and equality. If the women smiling mutely from its pages had been white instead of black—if they had been blessed with the same financial advantages, faced fewer obstacles in accessing medical services, and received the same quality of care that many white people enjoy—there might be 30 fewer in the book, the statistics say, and today dozens of black families might not be grieving the irreplaceable loss of a mother, a wife, a sister, a daughter. Haley knows all about the cruel racial imbalance in the statistics. "I'm tired of saying goodbye to women who should still be here," she says.

|

|

It would be terrible enough if breast cancer were the only disease that discriminated so unfairly. But it is not. From heart disease to HIV, depression to diabetes, minorities in Chicago, as well as throughout the United States, suffer higher rates of illness than people of European descent. "It's hard to name a [health] condition where these disparities don't exist," says Steve Whitman, director of the Sinai Urban Health Institute, on Chicago's West Side.

The good news is that overall health has generally improved among all racial and ethnic groups over the past few decades. And because health has improved more for minorities than for whites on many measures, the country has made strides toward closing its racial divide in health. A study by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, revealed a narrowing of racial disparities nationwide on 11 of 14 health status indicators in the 1990s, and a widening on just three.

The bad news is that the gaps remain stubbornly wide, and that Chicago is out of step with the country in narrowing disparities. To gauge this city's progress, Whitman and his colleagues at Sinai Urban Health Institute gathered Chicago-specific epidemiological data on the same 14 categories measured by the CDC. And they found that on 11 of the 14 measures, the gap between blacks and whites got wider in the nineties, largely because blacks locally did not show as much improvement in health as whites did (Hispanics and other ethnic groups were not included in the findings). "There is something about black and white health outcomes in Chicago that is going in exactly the wrong direction," concludes David Ansell, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center.

Because standardized data on racial and ethnic health disparities in specific cities are not readily available, it's hard to know exactly where Chicago ranks among its urban peers. "If you line up the 50 biggest cities, different ones will be worst on different measures," Whitman says. "I don't know what we're uniquely bad at." Still, over the past several years Whitman's organization—the research arm of Sinai Health System, which operates Mount Sinai Hospital—has conducted a number of other studies in Chicago that, taken together, paint a disturbing picture of a city in which poor and minority populations bear an undue burden of preventable disease, suffering, and early death. If the city's black population enjoyed the same level of health as its white population, Sinai researchers contend, the average African American in Chicago would live eight years longer than he or she does today. Meanwhile, 4,000 fewer local African Americans would die each year—an annual toll that surpasses all U.S. military deaths thus far in Iraq.

"If a Martian landed in Chicago and you walked down the street and told him that, on average, this person is going to live eight years less than that person, the Martian would say, 'How in the world do you know that?'" Whitman says. "And I'd say, 'It's simple: We've arranged things in this country so that the darker your skin, the shorter your life will be.'"

If Whitman is right—that our racial divide in health results from the way we've arranged things—it seems at least possible that we can rearrange things to close it. That is the big idea behind several initiatives now under way in Chicago. It's too early to say whether any of these efforts will make a dent in the problem. And no one underestimates the difficulty—the causes of disparity are dauntingly complicated, inadequately understood, and resistant to easy fixes. "There's no magic bullet," says Marshall Chin, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago who studies racial and ethnic disparities in medical care. But perhaps now there is hope that real progress is within reach.

"Long term, I think we can look forward to the elimination of health disparities," says Jim Webster, a professor of medicine at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine and president of the Chicago Board of Health. "Given the data we have and what we know about prevention, I think that 20 years from now we'll be able to say, We had a big problem, and we fixed it."

Reaching that goal, though, will require an unprecedented degree of cooperation among health care providers and a level of leadership from our public servants that, so far, has been as elusive as a cure for the common cold. The question is, will the right people be listening?

|

|

Ask a dozen experts what causes health disparities and you may get several dozen explanations—starting with "Nobody really knows." The hypotheses include myriad social, financial, and cultural barriers to medical care, poor quality of care, racial segregation, lousy schools, fear, ignorance, rat- and roach-infested substandard housing, an "apartheid" health care system—separate but unequal, poor health education, deficits of "cultural competence" and sensitivity among care providers, shortages of doctors and medical facilities in blighted communities, lack of diversity among the ranks of health care workers, misguided public health policy emphasizing treatment over prevention, havoc wreaked on genes by a stressful urban environment, breakdown of the traditional family, crumbling of the public health infrastructure, complexity in navigating the health care maze, and much more. Instead of asking what causes health disparities, a better question might be: What doesn't?

Many experts agree, though, that the problem essentially stems from a few root causes: poverty and historical patterns of racism. From where he sits on the West Side of Chicago, Steve Whitman is reminded daily of the impact of poverty and race on health. Out the window of his office at Mount Sinai Hospital, he sees an unending river of human misery flowing from largely African American North Lawndale and predominantly Hispanic South Lawndale—adjoining neighborhoods on the city's West Side in which poverty and poor health form a menacing tag team. Median household income in these communities is well below that of the city and the country, and perhaps half of the adult population are without any kind of health insurance. Lacking basic coverage, many people simply go without regular primary care and thus fail to get needed tests and follow-up care as well. Often it is only when illness sets in and symptoms become acute that they seek help at a place like Mount Sinai Hospital—a nonprofit provider that offers care regardless of a patient's ability to pay—and by that time it may already be too late (nationally, uninsured adults with cancer, for example, are 25 percent likelier to die than cancer patients with health coverage, according to Baylor College of Medicine's Intercultural Cancer Council).

The distress of the underprivileged and underserved gnaws at Whitman. He sees health disparities as "a terror visited on black people," and society's failure to remedy the problem a form of racism. "I hate racism," he declares. "I hate unfairness. It dehumanizes all of us. As a white person, I understand how much I and most other white people benefit from it, and I hate that as well."

Whitman and other researchers connected with Sinai deserve credit for raising awareness about local health disparities. In addition to the epidemiological studies, they have conducted extensive, face-to-face surveys of residents in a handful of city neighborhoods—five of them predominantly poor and minority—showing a strong correlation between socioeconomic status, race or ethnicity, and health. On virtually every measure, people in the survey's one middle-class white community (Norwood Park, on the Northwest Side) fared better than people in the five poorer minority communities on the South and West sides (African American North Lawndale and Roseland, Hispanic South Lawndale and Humboldt Park, and racially mixed West Town). Among the findings:

- Forty percent of adults in North Lawndale lacked any form of health insurance—which sounds bad enough, but when one crosses into South Lawndale, the rate jumps to 56 percent.

- The death rate from diabetes among Puerto Ricans in Humboldt Park and West Town was more than twice those of Chicago and the United States, and was believed to be the highest recorded anywhere in the country. Meanwhile, the rate among black residents in the survey was also extraordinarily high, at almost double that of whites locally and nationally.

- Some 34 percent of the Puerto Rican children in the study had asthma, the highest rate recorded anywhere in the country, prompting Whitman to dub Chicago "the asthma capital of the United States." Meanwhile, 25 percent of African American children had asthma, much of it going untreated. By contrast, 10 percent of children nationwide suffered from the condition.

The list of health calamities did not end there. Heart disease, various forms of cancer, arthritis, and other afflictions that can be prevented through a healthy lifestyle and regular primary care—or effectively managed if detected early and treated—are also cutting a swath through these communities. The survey turned up pockets with extraordinarily high percentages of hypertension, tobacco addiction, and obesity, including what Whitman says are the highest levels of childhood obesity ever measured anywhere—no surprise, given that large areas of the South and West sides lack adequate recreational options and qualify as "food deserts," places so bereft of decent grocery stores that it is easier to buy french fries at a nearby fast-food restaurant than to get fresh produce from a grocer that may require several bus rides to reach.

Some of the findings—such as those for diabetes and pediatric asthma—garnered local headlines and certainly created the impression that Chicago is in the throes of "a regional health care crisis," as Rush's David Ansell puts it to me. And undoubtedly these findings offer a vivid and startling snapshot of health conditions in some of Chicago's neediest communities. But does that make Chicago any more awful than any other place?

"I'd be careful about claiming things are worse here," cautions the U. of C.'s Marshall Chin, director of Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change, a program funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation that seeks to improve the quality of health care for racial and ethnic minorities. "You'd be safer saying disparities in Chicago are comparable to those in other big cities." Still, in dozens of interviews for this article, no one I spoke to disagreed with the basic thrust of Sinai's research. "The point is that this is an unacceptable level," Chin says.

|

|

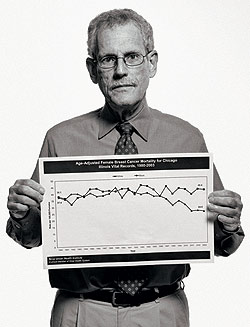

Of all the dire health issues in the city, perhaps none is more troubling—and mystifying—than the black-white disparity in breast cancer mortality, which grew from a crack to a gap to a chasm over the course of two decades. Throughout the 1980s, breast cancer killed black and white women in Chicago at roughly the same pace, resulting in about 38 deaths per 100,000 each year. But starting in the early nineties, the rate for white women began to nose downward, while the rate for black women remained stubbornly aloft. By 2003, the rate for white women had fallen to about 24 deaths per 100,000; for black women it had actually ticked upward, to about 40 deaths per 100,000—producing a 68 percent divide, according to Sinai data, nearly double the size of the national black-white gap.

The improvement for white women was easy enough to explain. The best defense against cancer is to catch tumors early and treat them before they can grow and spread havoc to other parts of the body. Years of efforts to raise awareness about the importance of breast self-exams and regular mammography screenings—x-ray images that can often reveal changes in the breast before they can be felt by hand—coupled with improvements in mammography technology, meant that more tumors were getting detected early, literally making the difference between life and death for growing numbers of women. Meanwhile, advances in treatment further upped survival rates. It wasn't that the incidence of breast cancer for black women had climbed locally—it remained below that of white women, says Monica Peek, an assistant professor of general internal medicine at the University of Chicago. "It's that black women were not seeing the benefit of what medicine had to offer."

"For black women in Chicago, we are exactly where the whole nation was 20 years ago," says Carol Ferrans, deputy director of the Center for Population Health and Health Disparities at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Cancer Center. "And other big cities, such as New York, have kept pace much better. It's an embarrassment for us, because it's not an urban problem all over the United States. It's particularly bad here in Chicago."

* * *

What could explain the divide? Some theories are not specific to Chicago. A growing body of evidence suggests, for example, that women of African descent are susceptible to a form of breast cancer—the one that Martha Haley is fighting—that attacks at a younger age, progresses more aggressively, and is less responsive to treatment than the breast cancers that strike women of European descent. What's more, studies on the subject—including one at the University of Chicago and one at the University of Illinois at Chicago—are examining how stress from the social environment may make women more vulnerable to sporadic gene mutations that can trigger this early form. "I think the mistake we've made in health disparities is we've said it's either nature or nurture," says Sarah Gehlert, director of the University of Chicago's Center for Interdisciplinary Health Disparities Research. "We think it's an interaction of things—maybe 30 percent genetic, 40 percent health behavior, with shortfalls in health care, environmental exposure, and social circumstances making up the rest."

Important as that research may prove to be—suggesting, for example, that African American women may need to get regular mammography screenings earlier than the age of 40 that is now the recommended benchmark for all women—it does not adequately explain why Chicago's disparity in mortality is so large and apparently getting larger. Among local health care leaders and breast cancer experts, there's no shortage of other theories, many of them having to do with the kind of intractable underlying social issues that can be found in any big city but may be particularly acute in parts of Chicago.

"Women who are disadvantaged face tremendous hurdles in trying to access the sort of health care that women who have insurance and money have easy access to," says the UIC's Carol Ferrans. "We all know that not all women of color are low-income, so the problems we're identifying are true of all financially disadvantaged women in Chicago. But because we have a disproportionate number of women of color at the low end of the income spectrum, we use color as a surrogate for financial problems." For many such women, she says, something as critical as an annual mammography screening, which can cost $50 to $150, is simply "not a priority in their lives because they have so many other crises and need money for so many other things, like food and rent."

With the erosion of employer-sponsored health care coverage swelling the ranks of the uninsured and underinsured, basic medical care has gotten too expensive for growing numbers of working women. "If people have to choose between health care and feeding and clothing their kids, they often put off health care," says Elizabeth Marcus, a breast cancer surgeon at John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital of Cook County. Result: "Their diseases get treated at a much later stage," she says, "when it's harder and more expensive to care for them."

Even women who understand the importance of annual screenings can find it confusing to navigate the system. The city's health care network is a hodgepodge of public and private hospitals and clinics, with little communication between them and little coordination between supply and demand. "For women in the southland—Ford Heights, Chicago Heights, Harvey, poor areas on the South Side—access to mammography screening sites is really poor," complains Barbara Akpan, a breast cancer survivor and advocate. "Women are falling through the gap—they don't know where to go."

Then there are the logistical hassles that must be overcome. "If you live in Roseland or South Chicago, you may have to travel all day [on public transportation] to get to a place for screening," says Richard Warnecke, director of the Center for Population Health and Health Disparities at the UIC Cancer Center. Arranging for child care and enduring long waits at overburdened clinics and public hospitals only add to the problem. "If you're the only income winner for the family, you may not be able to take time off work" for screening or treatment, says Ruta Rao, assistant professor of medicine in the division of hematology and oncology at Rush University Medical Center. "Or you may not be able to find someone to watch your kids."

At every stage of medical need, from screening to diagnosis to treatment, these challenges accumulate. Having breast surgery may require missing a week of work and spending additional time on follow-up visits; radiation treatment may require daily visits to a medical facility for weeks. Faced with so many barriers, many women fail to follow through with care. At institutions in Chicago that serve low-income women, the rate of loss to follow-up care can run as high as 25 to 30 percent, says Ansell.

|

|

Surely disadvantaged women in other big cities face socioeconomic challenges similar to those confronting women in Chicago. Yet in New York City, the racial disparity in breast cancer mortality is less than a quarter the size of Chicago's. New York has also made significant progress in reducing racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes and asthma, according to Kevin Weiss, director of Northwestern University school of medicine's Institute for Healthcare Studies. One possible explanation for New York's success is that there are 11 public hospitals distributed across the five boroughs. Those hospitals and the network of health clinics integrated into them sit in close proximity to the people they serve, and are managed by highly qualified professionals who understand how to deliver care where it's needed most, says Pat Terrell, former deputy chief of the Cook County Bureau of Health Services and now a principal with Health Management Associates, a Chicago-based consulting firm.

The Chicago area would seem to boast its own enviable public health care infrastructure. Among the county's medical assets is John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital, the state-of-the-art facility that replaced the aging Cook County Hospital in 2002, and a network of health clinics that was expanded in the 1990s to help form what Weiss calls "a remarkably strong and competent ambulatory care system." The county's public health safety net was further augmented by partnerships with private community hospitals whose services eased the burden on Stroger Hospital. But now "that network needs specific attention if it is to continue to flourish," says Terrell. Meanwhile, says Weiss, the county's ambulatory care system is being "dismantled"—the result of a financial reckoning that has been building for decades, other observers say.

A possible reason for the financial storms buffeting the county health system is that it lacks sufficient funding to accomplish its mission. Indeed, says Terrell, the per capita contribution to health care in Cook County is at the low end compared with similar public systems elsewhere in the country.

Robert Simon, interim chief of the county health bureau, says it has been 12 years since the county passed a tax increase to fund health care, during which time costs have skyrocketed by more than 500 percent. "The leaders in the city, the county, and the state must find a way to provide us with more money," he says.

But critics argue that the bureau's financial woes are self-inflicted and due mostly to its wasteful and politicized organizational model—the kind that has been abandoned by almost every other big-city public health system in the country.

In New York City, for example, a public benefit corporation, separate from local government, runs all public hospitals and clinics. It is overseen by an independent board of directors loaded with experience and expertise in the complexities of large-scale health care delivery. By contrast, the Cook County Bureau of Health Services is an arm of county government, overseen not by a board of independent advisers drawn from the health care field but by the politicians who make up the Cook County Board of Commissioners. Strategic planning is almost nonexistent, critics assert. All hiring and firing falls under the authority of the board president, Todd Stroger, who has no experience in health care management, though he is well versed in Chicago's special brand of machine politics (his father, for whom the new county hospital is named, preceded him as county board president).

Todd Stroger has been in the news a lot this year for acts such as handing out lucrative jobs and raises to friends and relatives—he nominated his cousin to be the county's $143,000-a-year chief financial officer—while shutting down a dozen health clinics and eliminating hundreds of doctors, nurses, and other frontline medical workers. Critics have assailed him for cutting too little bureaucratic fat from county government, of which the Bureau of Health Services is the second-largest division, though he and Robert Simon have insisted that there is no more bureaucracy or patronage left there to trim. "As a doctor, I can't bear to see the elimination of primary and preventive care services," says Simon. "But I challenge the critics to look at our budget and not just find fault with our decisions, but tell us what they would cut instead."

A chronicle of the ills that plague the county's public health care system could fill a book. But suffice it to say that the recent budget crisis and service cuts are merely the latest manifestation of dysfunction in an organization that for years has served as a case study in bureaucratic bloat, managerial incompetence, prodigal waste, and nonaccountability. The bureau "has too often been used as a patronage dumping ground for politicians, sucking precious resources away from delivery of health care to people who need it in the neighborhoods," says Forrest Claypool, a Cook County commissioner who has pushed for reform of the county's health care system.

* * *

Stroger Hospital's mammography clinic offers an example of the difficulty the bureau seems to have in anticipating demand for services and allocating resources effectively. By late last year, scheduling problems had created a backlog of more than 10,000 women seeking routine screening or diagnostic mammograms, according to attending radiologist John Keen, producing waits for appointments, other observers say, that stretched for months. "And waiting, of course, translates into later stages of disease and worse outcomes," says Carol Ferrans. "Two or three or four months can mean the difference between lumpectomy and mastectomy, the difference between catching the disease in time and having it spread through the body."

To address the problem, the hospital started referring symptom-free women seeking only screening mammograms to other hospitals and clinics. From there Stroger's radiologists and technicians focused on whittling down the backlog of 5,000 remaining women waiting for diagnostic mammograms—given to a woman with an abnormality or a lump in her breast. Owing to the hospital's limited resources, Keen reasons, it made sense to focus on the higher-risk cases. And he said the hospital hoped to have its backlog eliminated by the end of September. Still, there's no guarantee that demand for services won't swamp capacity again. "There are so many women, and just one hospital," Elizabeth Marcus says.

Another sign of troubles at Stroger: For a time the hospital operated two mammography vans that traveled through the city's poorest neighborhoods, offering breast cancer screenings to women who otherwise might not have had the wherewithal to get them. But funding for the vans ran out; their equipment is outdated, dilapidated, and in disrepair; and the vehicles now sit idle. According to Keen, the hospital is working on lining up funding for a new fleet of vans with state-of-the-art digital equipment that can process more breast images and at higher quality.

Despite the hospital's efforts to fix its mammography problems, the rampant shortcomings at the Bureau of Health Services raise questions about whether the county, neck-deep in the duties of governing, is up to the task of managing an enormously complex public health system. And the bureau's troubles argue for reforms along the lines Todd Stroger's own Health Care Transition Committee recommended in a report that has not been released to the public. Among the prescriptions, according to Quentin Young, a Hyde Park physician and former director of medicine at County Hospital who chaired the committee: Launch a nationwide search for qualified leaders; create an independent hospital board of health experts, as other cities have done; and install teams of financial and human resources professionals untainted by patronage.

|

|

For Rush University Medical Center's David Ansell—who helped set up Chicago's first breast and cervical cancer screening program at Cook County Hospital in 1984—the relentless pace of breast cancer mortality among black women in Chicago came to feel deeply personal. Ansell had dedicated his career to fighting the disease, to saving lives. Yet the undiminished death rate among African American women afflicted with the disease whispered to him of failure. "I looked at 20 years of my work and said, Breast cancer [for black women] hasn't budged," he says. "Everything we're doing in Chicago—our best efforts at prevention and treatment—have not made a difference."

To bring attention to the problem, Ansell last year teamed with Sinai's Steve Whitman and Jocelyn Hirschman to analyze local data for breast cancer mortality and formulate hypotheses to explain it, which they detailed in an article published in the journal Cancer Causes & Control. But rather than let the article serve as the last word, they decided to go a step further—by trying to do something about the problem. To make any kind of headway, they knew they would need to engage the entire community of care providers, researchers, advocacy groups, and foundations. They also knew they would need to recruit a leader from the local community with the clout, connections, and stature to pull together such a diverse constituency.

They settled on three candidates: Ruth Rothstein, former chief executive of the Cook County Bureau of Health Services and now chair of the board at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science; Sister Sheila Lyne, CEO of Mercy Hospital and former commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health; and Donna Thompson, CEO of Access Community Health Network. Ansell and Whitman hoped one of the three would agree to head the breast cancer task force they envisioned. To their surprise, all three agreed to serve as cochairs, and the task force came together.

Over the course of this past spring and summer, more than 100 doctors, researchers, advocates, and other experts participating in the effort met frequently to address specific areas suspected of contributing to the high rate of mortality among black women. They gathered at night and on weekends, trading countless e-mails and phone calls in between, applying the wisdom of a very smart crowd to a knotty problem. "We have the entire community engaged, from different disciplines, all sitting around the table together," Ansell says. No one has been paid a dime. "All this has been done in a really quick time frame, and it's been a monumental amount of work," says Elizabeth Marcus.

The task force intends to produce a report containing recommendations on the structural and public policy changes that must occur to address the breast cancer problem. "I don't think the solutions will be easy, but they'll be doable," Marcus says. Although the report had not been completed by press time—it is to be unveiled to the public on October 17th—the task force was focusing its attention on three main areas.

-

Access to mammography. "Our system is so fragmented," says Ferrans. "Women know about Stroger Hospital, but they don't know they have other options—and options much closer to home—where they can get low-cost or no-cost diagnosis and treatment." They also need to be given greater awareness about federal money available through the Illinois Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Program, as well as private funding through community and advocacy groups—much of which goes unused and gets returned at the end of each year.

The current system is so confusing that often providers themselves don't know what options are available. "There is a huge disconnect between all of the players," Ferrans says. "One of the things we hope to accomplish is better communication between the providers and the community, and closing some of the huge holes we have in the safety net."

-

Quality of mammography. Women who go for annual mammography screenings can reduce their chances of dying of breast cancer by up to 30 percent. But mammograms are often inconclusive and difficult to read. It helps to have the best equipment, and multiple sets of expert eyes scrutinizing the x-ray for abnormalities—luxuries that strapped clinics serving the poor often go without. "Mammography is a complex thing," says Paula Grabler, a radiologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital who specializes in breast imaging (she's also the wife of David Ansell). "Anyone can pick up a large tumor. But is the technologist highly skilled to see all the cancers, especially the tiny stuff? Because finding those gives the best chance of survival.

Grabler knows of a local organization providing mammograms to poor women that was catching just two cancers per thousand. The number should have been at least six—meaning it may have been missing four cancers per thousand women. She and others suspect that these numbers point to poorer quality of mammography among some providers, possibly due to a shortage of skilled technicians and radiologists. But because institutions are not required to measure for quality, they don't know for sure. Her hope is to get institutions to start sharing all of their results on a confidential, transparent Web site. The data would be audited—not to point a finger at providers that are falling short but to identify where the problems are and get support to where it's needed.

- Quality of treatment. Even for those with access to care, the treatment itself may not be up to the standards that people living in more affluent areas enjoy. The group looking into this area would like to identify best practices and establish quality benchmarks that providers around the city would strive to meet—again reporting their results confidentially to pinpoint which institutions are meeting the standards and which need help.

The people pouring their energy into the breast cancer task force know they can't fix poverty and racism and the ills that flow from them anytime soon. But there's plenty they can fix. They hope their cross-institutional, multidisciplinary approach to the breast cancer problem will serve as a model for fighting other health disparities in Chicago, such as for diabetes and asthma.

Simply making better use of the funds and facilities already available locally would be a step in the right direction. "We have significant resources, but we need to streamline and allocate them more efficiently," says Adrienne White, vice president of health initiatives and advocacy for the American Cancer Society's Illinois division. The problem, says the UIC's Richard Warnecke, is that the various public and private health care organizations "operate independently, and nobody has tried to organize them."

The task force's emphasis on improving quality of care also has the potential to act as a rising tide, lifting other boats. "We know that if you can improve quality of care by measuring it, being transparent, being better at what you do, then you can reduce racial disparities," Ansell says. "The solutions are out there. But we have to view ourselves as part of the problem."

Finding those solutions will require better coordination and communication between public and private sectors—cooperation that has not come naturally to local health care institutions in the past. "What Chicago has not done is choose to begin to work as one community to solve this problem," says Kevin Weiss. "That will require civic and public leadership." Similarly, delivering greater equality in health to all citizens—such as by implementing reforms in the county health system—will take the kind of leadership local politicians have long seemed allergic to. "There's going to have to be some political will to make changes," says Marcus.

Given those hurdles, what's to prevent the breast cancer task force's recommendations from disappearing into the void of good intentions gone nowhere? "We're hoping there's a moral imperative—that we see the urgent state of affairs and do something about it," says Monica Peek. "The question is, are people willing to do the right thing?"

If defenders of the status quo need any further spur to action, perhaps they need look no farther than Martha Haley and her book of remembrance. Knowing that her time is running short, Haley has arranged for another woman in her support group to take over the job of adding photos and recollections of the dead after she is gone. Some fine day, there should no longer be a need for such an agonizing chore.