O’Hare expansion is encroaching on St. Johannes Cemetery.

In the 1840s, the Kolze brothers—Henry, William, and Frederick—left behind the kingdom of Prussia for the prairies of Illinois. Settling on the wild but fertile lands northwest of the growing city of Chicago, they and their compatriots carved out farms and orchards, raised families, and established a church with an adjoining cemetery—where, following their deaths, they were buried. As the decades passed, a hectic urban pace slowly replaced the rural community’s seasonal ebb and flow, a change especially evident at a tiny local airfield, which, in the years after World War II, transmogrified into one of the world’s busiest transportation centers: O’Hare International Airport.

But now those long-dead Kolze brothers have risen up to halt the march of progress. For the last eight years, they and their 1,200 neighbors interred at the verdant 160-year-old St. Johannes Cemetery have stymied efforts to launch O’Hare into the 21st century. Not far from downtown Bensenville, right at the point where Cook County butts up against DuPage, the Kolzes’ final resting place stands smack in the path of a planned 10,000-foot-long landing strip dubbed Runway 10 Center. Slated to open in 2012, and an integral part of Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley’s multibillion-dollar plan to modernize O’Hare, the runway is currently little more than a narrow line on a blueprint. Although preliminary work has begun on 10 Center’s east and west ends, the city has yet to acquire the land that lies between them. That’s where St. Johannes Cemetery sits, about a mile east of the intersection of York and Irving Park roads. The descendants of the people buried there want to hang on to the five-acre burial ground until, as the New Testament has it, the final trumpet sounds and angels are sent forth to gather the elect.

Which obviously presents a problem for the folks trying to rearrange O’Hare. “You can’t build a runway with a curve in it,” says Rosemarie S. Andolino, Chicago’s commissioner of aviation and, since 2003, the executive director of the O’Hare Modernization Program. Runway 10 Center is a crucial part of that program—“of a compelling governmental interest,” to cite the secular legal argument—and therefore the cemetery must go. After a fiercely waged legal battle, it appears that airport authorities may soon be allowed to disperse the bodies resting at St. Johannes to neighboring cemeteries.

Not so fast, say the cemetery’s champions. “If anyone out there thinks we’re not operating with a lot of faith, they’re mistaken,” says Bob Sell, a spokesman for the church affiliated with the cemetery. “We’re not giving up.”

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo by George Thompson

|

|

Like many of the folks fighting to preserve the cemetery, Sell has connections to the land around O’Hare and St. Johannes that extend back into the middle of the 19th century. One of his great-great-great-grandfathers, Christian Dierking, farmed the property now occupied by the United Airlines terminal. Another great-great-great-grandfather was Henry Kolze, who, with his extended family, left an indelible mark on the land he settled. The suburb of Schiller Park, just east of the airport, was originally known as Kolze (pronounced COAL-zee), and today the largest monument at St. Johannes Cemetery, a 30-foot-tall obelisk, bears the Kolze name.

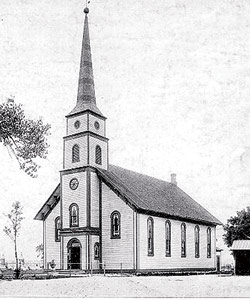

With other immigrants from the German empire, Sell’s ancestors founded what is today St. John’s United Church of Christ. They built their first church in 1849, and that July, the congregation buried Catherine Wille in the adjoining graveyard, the first person laid to rest there. More graves followed, and in 1873, a new church went up. The most recent burial occurred in 2006.

According to Sell, parishioners—who fervently believed that the dead, once buried, should lie undisturbed until Judgment Day—would traditionally tend to the graves following Sunday morning services. This ritual went on for decades, as did the steady seasonal pace of the agricultural community. Things only began to change after World War II when the city of Chicago, looking to ease overcrowding at Midway Airport, began buying up the land around a little airport northwest of downtown. Known either as Douglas Field or Orchard Place, the airport was rechristened to honor a navy pilot and slain war hero named Edward “Butch” O’Hare.

To make way for O’Hare’s new and longer runways, church officials sold most of their land to the city. In 1952 they hoisted the church up on wheels and moved it into Bensenville, where it stands today on Route 83; a tall black cross in the cemetery marks the church’s original location. The five-acre cemetery remained behind, still the property of St. John’s, and today it’s hard up against the cargo depot and fleet of jets owned by FedEx. Just to the north, United and American jets taxi toward takeoff; passengers gazing out the windows can see a seven-foot-tall sign that cries out in big blue letters: DON’T TREAD ON US! AMERICAN, CHICAGO, UNITED! SAVE OUR CEMETERY!

|

|

The battle to save St. Johannes Cemetery began in the summer of 2001 after Mayor Daley announced his intentions to modernize O’Hare, where an antiquated layout of intersecting runways had slowed air traffic locally and nationally. By extending old runways and building new ones, Daley’s plan reconfigured the airport into six parallel runways, which would increase capacity and limit delays, all at a cost of $6 billion—money that would come from passenger ticket taxes and general airport revenue bonds, as well as contributions from the federal government. (The anticipated cost of the project has since escalated to $8 billion, which the city attributes to inflation.) In addition, billions more are needed for new roads around the airport, a proposed extension of the CTA Blue Line, and other improvements. What’s more, the airlines, confronted by shrinking revenues, are now suggesting the city rethink the breadth of the expansion plan.

That plan called for the acquisition of more than 400 acres and the demolition of hundreds of suburban homes and businesses, primarily in Bensenville and Elk Grove Village. It also required the relocation of bodies buried not only at St. Johannes but also at Rest Haven Cemetery, a Methodist burial ground with about 110 graves some 350 yards south of St. Johannes.

As for St. Johannes, many of its allies in opposing the expansion have gradually fallen away. Changes to the original plan have scaled back the impact on Elk Grove Village, prompting its mayor, Craig Johnson, to say he will no longer oppose the plan. In hard-hit Bensenville, its longtime village president, John Geils, perhaps the most vociferous opponent of the expansion, recently lost a bid for reelection; his successor, Frank Soto, has signaled a willingness to cooperate with airport officials. Even tiny Rest Haven Cemetery is no longer involved in the battle; the relocation of a planned cargo depot means Rest Haven can stay where it is—though it will one day adjoin a concrete apron leading into the cargo bay.

Nonetheless, the supporters of St. Johannes vow to continue the fight, their resolution fueled, in part, by what they see as Daley’s arrogant introduction of the plan as a fait accompli. “There were no negotiations,” says the Rev. Michael Kirchhoff, a member of St. John’s church. “The city simply made an announcement that they were going to take the cemetery.” Chicago city officials counter that they reached out to church leaders, making an offer in March 2006 of $630,000 for the cemetery land. (Then, as now, the city also agreed to absorb all costs of relocating the bodies.) “We would accept no amount of money,” Kirchhoff declares. “This is sacred land, not to be bartered away.”

* * *

Photography: (Image 1) Kim Thornton, (Image 2) Courtesy of St. John’s United Church of Christ

|

|

From the beginning, city officials have regularly expressed empathy for the descendants of those buried at the cemetery. “We understand their plight and want to be sensitive to their needs,” says Commissioner Andolino. “But the airport is of national significance—and cemeteries have been moved before.”

There’s little argument on that front. In 1955, more than 2,000 graves were moved from Waldheim, Forest Home, and Concordia cemeteries in Forest Park during construction of the Eisenhower Expressway. Forty years later, Lombard officials approved the relocation of 170 graves within Allerton Ridge Cemetery—an overgrown burial ground that had been acquired by a private developer—to make way for a shopping mall. Most famously, in an effort to ward off cholera and other health hazards in the years following the Civil War, Chicago cleared out some 35,000 bodies from its old North Side city cemetery, an effort abetted by the great fire of 1871. Today those grounds compose the southern end of Lincoln Park, where one mausoleum—the tomb belonging to Ira Couch and his family—still remains immediately north of the Chicago History Museum.

Despite the city’s best efforts, the Couches weren’t the only ones left behind, and bodies continued to surface in the ensuing decades. In 1998, during construction of a parking structure at the history museum, workers uncovered the skeletal remains of another 80 bodies. Having lain forgotten for more than a century, the bodies were essentially unidentifiable, and today they reside at the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency in Springfield. “We’re just holding them in case any relative can come forward and claim them,” says Dawn Cobb, the coordinator of the state’s Human Skeletal Remains Protection Act.

Three years ago, Cobb visited St. Johannes, and should O’Hare get the OK to disinter the bodies there—a task that would be handled by the cultural-resources branch of the well-respected Louis Berger Group—she and her office would help oversee the move. “Honestly, I’ve never encountered anything this large,” says Cobb, who has helped relocate significantly smaller rural cemeteries. The relocation of the bodies at St. Johannes “could certainly take months,” she says, and is dependent on things such as the weather and the size of the removal crew. Though a backhoe might be used to remove the first layer of topsoil—just enough to reveal the grave shaft, says Cobb—much of the work would have to be executed with trowels, hand picks, and brushes, all under the watchful eyes of an archaeologist and a skeletal analyst.

Given the age of some of the graves, Cobb is unsure what the diggers will discover. Most of the wooden coffins will likely have disintegrated, leaving behind only a few nails and pieces of metal hardware. Depending on the acidity of the soil, there may be some perfectly preserved skeletons, or merely bone fragments or bone meal—“the shadow of where the bones used to be,” explains Cobb. “Workers will document everything in the grave. We want to make sure everything is removed and reburied as a unit.” Wherever possible, the old grave marker will be used on the new grave. “It’s such a sensitive issue,” says Cobb. “Workers will be cautious and very respectful.”

For the relatives of those buried at St. Johannes, those good intentions aren’t enough. “In 1849, when the first burial took place, there was this sense of committing somebody to God’s care for eternity,” says Rev. Kirchhoff, who has a great-great-grandfather and descending generations of his family buried at the cemetery. And that’s the sticking point: As even the courts acknowledge, “a major tenet of [the St. John’s congregation’s] religious beliefs is that the remains of those buried at the St. Johannes Cemetery must not be disturbed until Jesus Christ raises these remains on the day of Resurrection.”

So who has the more compelling need: the city of Chicago, the O’Hare Modernization Program, and the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA)—or St. John’s church-goers worried about the well-being of their relatives’ eternal souls? For an answer to that question, the contending parties ultimately turned not to a heavenly tribunal, but to the U.S. judicial system.

* * *

Chicago Tribune photo by George Thompson

A bare cross in the cemetery memorializes the original site of the relocated church.

In 2001, after Mayor Daley announced his plans to expand O’Hare, the cemetery’s champions turned immediately to the courts. Assisting them was Joe Karaganis, the Chicago lawyer who would also represent Bensenville, Elk Grove Village, and Rest Haven Cemetery in their opposition to the airport modernization. Initially waged in the district courts of Illinois and Washington, D.C., the fight involved a long series of complaints, restraining orders, injunctions, and writs—and in most cases, O’Hare got the better of the cemetery and its allies. “We’ve only won some minor battles in eight years,” admits Rev. Kirchhoff, “and Chicago has won all the major ones.”

Although some of the legal arguments put forth by the church had a secular basis, the central issue came down to religion. Karaganis and his colleagues focused especially on a section of the O’Hare Modernization Act (OMA), approved by the Illinois General Assembly in 2003, that effectively excluded St. Johannes from any statutory protections already in place. Invoking the First and Fourteenth amendments (which ensure, respectively, the right to freely exercise religion and equal protection under the law), the cemetery’s advocates skirmished with the airport expansionists before finally landing in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

There a three-judge panel ruled against the cemetery. Writing for the majority, Judge Diane Wood concurred with a lower court’s opinion that the OMA represented “no discrimination or targeting of religious institutions.” She also proffered what was, given her ruling, an unnecessary opinion: “If the decision were ours to make . . . ,” she wrote, “we would find that there really is ‘no realistic, economically practical alternative’” to moving the cemetery. (Dissenting in part, Judge Kenneth Ripple countered that the OMA had imposed a substantial burden on the free exercise of religion of the families of those buried at the cemetery, whose relocation, he wrote, would compel those families to forgo their “religious precepts.”)

In December 2007, the appeals court declined Karaganis’s petition that it meet en banc—that is, with all its judges hearing the case—and lifted an injunction preventing O’Hare from receiving title to the cemetery. Abandoned by their allies in fighting the modernization plan, supporters of St. Johannes may have finally run out of options. In the past, the U.S. Supreme Court has declined to hear the case, which suggests any pending or future appeals there would likely be fruitless. That leaves the cemetery’s fate hanging on an ongoing (and likely soon-to-be-resolved) condemnation case in a DuPage County court.

Karaganis, for one, is baffled by the decision of the appeals court. “I’m not particularly a religious person,” he says, “but I strongly believe that what we were founded on includes a protection of religious rights. It astounds me, the cavalier nature of what’s been done here. With all due respect to Judge Wood, I think it was a political decision.”

Despite the judicial setbacks, the congregation of St. John’s, falling back on its strong religious faith, insists the battle isn’t over. “I certainly know what we’re up against,” says Rev. Kirchhoff, who has a burial plot waiting for him among his ancestors at St. Johannes. “But I hold up hope that we will prevail.”

As for Karaganis, he too retains his faith in a higher power: the U.S. Constitution. “If the courts and the FAA and the city of Chicago follow the law,” he says, “we are confident the cemetery will remain. If not, the results will speak for themselves.”

Photograph: Megan Lovejoy