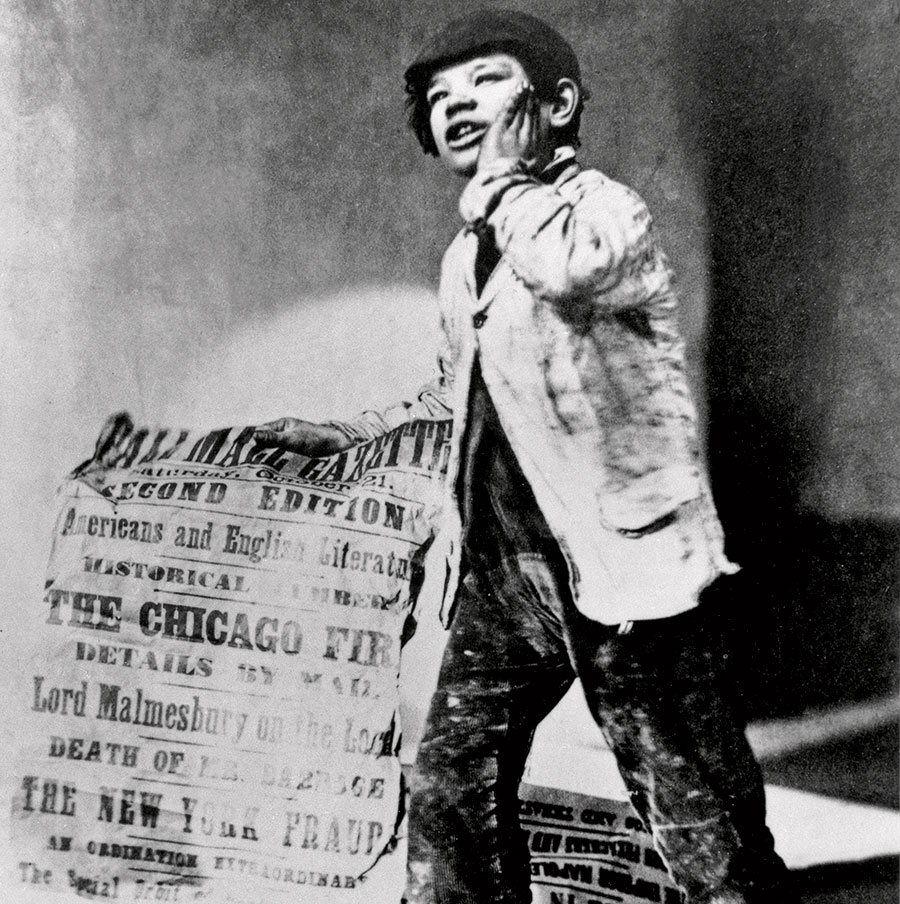

1 It was the original viral news story. The 1871 fire devastated Chicago just five years after telegraphs connected the United States and Europe, making it “the first instantaneously reported international news event, details of which reached an audience in the tens of millions,” Smith writes in Chicago’s Great Fire: The Destruction and Resurrection of an Iconic American City, out October 6.

2 It wasn’t even the deadliest fire in the U.S. that day. While Chicago was ablaze October 8, forests were burning around Peshtigo, Wisconsin, killing 1,500 — the most deaths from any fire in U.S. history. Chicago’s “miraculously low” death toll was probably in the low to mid-hundreds, Smith estimates. With the fire taking two days to spread up a four-mile path, most Chicagoans could see the fire coming and “had the opportunity to flee.”

3 It was legally dubious to call in federal troops. Mayor Roswell B. Mason handed over the “preservation of the good order and peace of the city” to the U.S. Army after the fire, without getting approval from aldermen or the elected board that oversaw Chicago’s police in that era. According to Smith, the mayor was responding to sensational newspaper stories about rampant looting and disorder in the smoldering city. After reluctantly taking on the job to police Chicago, Lieutenant General Philip H. Sheridan was praised by many for protecting the city. But Sheridan said those reports of violence had been nonsense, “without the slightest foundation.”

4 Chicago had its own version of “No soup for you!” The Chicago Relief and Aid Society was criticized for discriminating against the poor people, often immigrants, it deemed unworthy of aid. When the Cincinnati Relief Committee came to town and ladled out 4,000 gallons of free soup a day, the local counterpart objected, saying Chicago’s well-being depended on a “resolute hand” to make certain “that no man or woman capable of work be allowed to eat the bread of idleness.”

5 Mrs. O’Leary exonerated (again)! Dismissing the often-discredited legend that Catherine O’Leary and her cow started the blaze, Smith doesn’t point the finger at precisely what did. Instead, he echoes the police and fire commissioners, who criticized the city’s shoddy building standards. “The perpetrators of the fire were the people who built Chicago so heedlessly and the officials who let them do so,” Smith writes. “It was as if Chicagoans had purposely intended to construct a city they wished to burn down and then voted for aldermen and mayors who did little to stop that from happening.”