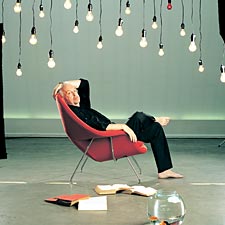

photograph by Andreas Larsson

|

Location: courtesy of A New Leaf Studio and Garden

Chair: courtesy of Design Within Reach  |

|

“I’ve been through analysis,” Falls says. “I’ve been through a great deal of reflection in my life. I’m a great believer in psychiatry, psychoanalysis, the psychological process, and I think we are all enormous products, finally, of our background and our parents.”

|

Robert Falls says he has grown “Scared Of Shakespeare”- an odd admission for a man who has spent his life in the theatre and whose 1985 production of Hamlet ignited his career. That show at the Wisdom Bridge Theatre opened with a coffin overflowing with blood on a bare stage. King Claudius held a televised press conference, attended by his queen in Nancy Reagan red. Del Close’s Polonius brilliantly channeled Henry Kissinger. The troubled young prince, played by Aidan Quinn, spray-painted a wall with to be or not to be.

Falls was 31 then. Jane Nicholl Sahlins, at the time on the founding board of Wisdom Bridge, remembers “a tall redheaded gangly guy doing fantastic stuff.”

Today, 52 and the artistic director of the Goodman Theatre, Falls remains physically imposing, although his six-foot five-inch frame is now capped with soft gray waves rather than the aggressive red curls of his youth. He has lost 70 pounds in the past year, but not his love for good food (“I put myself in the great Falstaffian tradition of hedonist,” Falls says), nor his appetite for the dramas of the modern American canon of pain, including his critically acclaimed productions of Eugene O’Neill’s plays and Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. As Falls explains, “I’m drawn to big, passionate, messy works, messy emotions, messy people, messy lives.”

For 30 years, he has been a force of nature on stages in Chicago and around the world, putting on huge, groundbreaking shows, winning accolades, suffering some flops, deriding critics, rescuing the Goodman, winning devotees and skeptics. Now, on a warm spring morning as he sits in the spacious backyard of his comfortable Evanston home, the setting somewhat belies his rambunctious past. The house, for example, features the blissful domesticity of the Falls clan, which includes his wife, Kat, and their three children, ten-year-old Declan, seven-year-old Vivienne, and four-year-old Connor. Many who know Falls say Kat and fatherhood have changed him.

“This was a kid who was a star director at 18. This is a guy who’s had it always,” says Stuart Oken, a close friend since college. “It was about his maturity as a human being catching up with his maturity as a director.”

Thinking back on his Hamlet, Falls says that he “knew nothing.” He was “bold and fearless and stupid and arrogant.” After that, he says, “I kind of fell off the Shakespeare wagon for 20 years.” Still, “what I would love to do is to get back to that same stupidity, that same boldness, that same fearlessness, which is very difficult now in my 50s.”

This fall he will have his chance. To mark his 20th anniversary with the theatre, the Goodman will open its 2006-07 season with Falls ‘s production of King Lear, starring Stacy Keach. The return to Shakespeare is more than a little daunting, but as the auspicious anniversary approached, Falls realized he “wanted to do something rather grand” that was “daring and challenging.” Fatherhood, he says, helped give him the courage to tackle this latest project. “When you identify with Hamlet your entire life, there comes a shift when suddenly you’re able to read Lear and identify with Lear.”

“I’m drawn toward big, passionate, messy works, messy emotions, messy people, messy lives.”

Falls has been praised for his astute direction of American theatrical classics that examine the psychological wreckage of tortured souls, and he recognizes that-in theatre, anyway-your personal life can inform and shape your professional output. “I’ve been through analysis,” he says. “I’ve been through a great deal of reflection in my life. I’m a great believer in psychiatry, psychoanalysis, the psychological process, and I think that we are all enormous products, finally, of our background and our parents.”

Falls spent his first 12 years in Ashland, Illinois . His mother, a farme r’s child, had persuaded his father to return to her small hometown near Springfield after they met and married at Florida Southern University in the early 1950s. Falls says his father, an Irish Catholic from New York, was always an outsider in downstate Illinois. Arthur Falls held a variety of municipal and political jobs, including running Gerald Ford’s 1976 presidential campaign in Illinois (Ford won here but lost nationally), before retiring from political activities and moving to Sarasota, Florida, in 1978. The two remain close, though the younger Falls is a longtime liberal.

Falls credits his first theatrical memory to his father. He recalls a reenactment for Ashland’s 100th birthday done in “an old West setting” and “my father rolling a cigarette onstage.” The young Falls was struck by two things: the “detail of a man onstage in a cowboy hat rolling a cigarette” and the fact that it was his father, who didn’t smoke. This glimpse into the notion of character and image made a lasting impression.

Art Falls, in turn, credits his late wife, Nancy, a homemaker, with starting their elder son’s theatrical career. Mother and son became close when the small boy broke his arches jumping off a bunk bed while playing Superman. His doctor prescribed home rest and special shoes. To entertain her child, his mother “bought him records of musicals, and that was a big influence on him,” Art Falls says. “You name any show in the forties, fifties, and sixties and he had them.”

When Bob was 12, his family-he’s the eldest of four children-moved to Urbana, where his father took a job in the admissions office at the University of Illinois and pursued a graduate degree in political science. Because he did not make friends easily, Bob felt isolated. When Art Falls transferred to the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle Campus, the family moved to Lombard and a whole new world opened up for Bob. “He just asked questions like mad,” recalls Ralph Amelio, Falls ‘s cinema studies teacher at Willowbrook High School.

Initially, Art Falls did not embrace his son’s life in the theatre. He had helped him get a legislative scholarship to the University of Illinois. “I thought that he had the voice, the intelligence, and the desire to be a lawyer,” Art Falls says today. About two weeks before Bob left for college, he persuaded his father that theatre was a better choice.

|

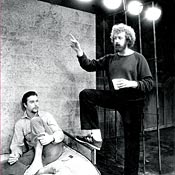

photograph: Matthew Modine |

| Falls photographed in 2004 by the actor Matthew Modine during rehearsals for Finishing the Picture |

Soon he had persuaded the critical world, as well. His student production of Michael Weller’s Moonchildren was good enough to land a spot at Chicago’s hallowed St. Nicholas Theatre, and won Falls-then a college senior-a Joseph Jefferson Award for outstanding direction. Richard Christiansen, the longtime Chicago Tribune critic, recalls being quite taken with that 1976 show and with Falls ‘s minimal production of John Steinbeck’s novel Of Mice and Men, which earned Falls his second Jeff Award. Of Mice and Men was strong enough, Christiansen says, to revive Wisdom Bridge and to catapult Falls into its artistic directorship. Soon Wisdom Bridge joined the list of theatres now seen as seminal to that fecund and magical period in Chicago stage history in the late seventies and early eighties.

In 1986, the Goodman came calling. Falls “was young, strong, done some stuff-not exactly my stuff-but the guy had the drive and we got him,” recalls Lewis Manilow, who was on the Goodman search committee and is the honorary president of the Goodman board. “It was a low point. Couldn’t have been lower financially. It was as low artistically, but he raised the artistic level.”

Falls made sure that he had help. He insisted that Frank Galati, who had been a contender for the job, be appointed Goodman’s associate director. And in his first year, Falls also brought in Michael Maggio as his second associate director. “It seemed fantastic, and it seemed absolutely appropriate,” says Martha Lavey, now the artistic director of the Steppenwolf Theatre Company. “And then, of course, the moves that he made in his early years were just so salutary.”

|

Photography: Left Eric Y. Exit |

|

Brian Dennehy with Kevin Anderson and Ted Koch in Death of a Salesman in 1998 |

Falls’s tenure began with his 1986 production of Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo. “That launched his career,” says Christiansen, who retired from the Tribune in 2002, “and the show itself was a calling-card production, saying this is what we can do here at Goodman Theatre.”

In those early, heady days, Falls promised “a new era,” with cutting-edge work and more musicals. His second season brought Pal Joey, which Falls calls “one of the more radical choices I’ve ever made.” The 1940 work was “so dark,” with “a cad as a central character” and “dialogue and lyrics [that] were cynical and biting and satiric.” An even edgier choice came in 1994, with Peter Sellars’s direction of The Merchant of Venice. Critics liked it; audiences left in droves, Falls admits. Still, he calls the show “one of [his] proudest moments at the Goodman.”

Falls developed a fruitful partnership with the actor Brian Dennehy, and the two rocketed to success with three Eugene O’Neill plays-most notably Long Day’s Journey into Night in 2002, which went on to New York-and Arthur Miller’s classic Death of a Salesman, which played to raves at the Goodman in 1998 before moving to New York and London. “There’s a lot of my father in Brian Dennehy,” says Falls. “He loves to laugh. He loves to fight, and he’s always willing, like my father, to demonstrate the intellectual superiority of the conservative over the weak-kneed, ready-to-cry-at-the-drop-of-a-hat liberal, which is true. Our emotionalism plays against us.”

“The two of us understand each other,” Dennehy explains. “It’s like a duet. It’s a piano and a violin making a third sound. We are prepared to go any place, to follow any line, to do any surgery, to say anything to each other, but all to make the thing work.”

The result is an intense and volatile collaboration that digs deep into the national consciousness. “It’s not an accident that our three most successful productions were Death of a Salesman, The Iceman Cometh, and Long Day’s Journey, and all three of these productions deal with the same basic theme, which is, America is not a success,” says Dennehy. “America is a failure for the people who need it most.”

Indeed, for all his success, Falls seems to carry a rich appreciation of failure. “Bob gets stuff because Bob’s so vulnerable,” explains William Petersen, the CSI TV star, who did two plays with Falls . “He exposes himself in such a way-and I don’t know if he does this intentionally or not-but you go, Oh, my God, I gotta strip some stuff down here [because] he’s out there, more naked than I am.”

“It’s a rather worthless breed of individuals,” Falls says of critics. “I think they should

just go away.”

Falls has talked frankly to his actors and tech crews about how his mother’s alcoholism informed his directing of Long Day’s Journey into Night. But such stories usually stay in the rehearsal room, a place from which he bars the media and other interlopers because he feels it is important to create a sanctuary for his actors. They, in turn, are only too happy to keep his secrets.

In 1991, Kathleen Moynihan , a Maryland native whose father was a professor of chemical engineering and whose uncle was Daniel Patrick Moynihan, made her entrance into Falls ‘s life. The two met at a party at the home of Frank Galati, one of Kat’s supervisors for her Northwestern University MFA. At the time, she had no idea who Falls was. “I just loved his confidence,” she says. “He’s just a very passionate personality.”

After 18 months, Kat was ready for a proposal. On a visit to her family’s Michigan cottage, she confronted Falls . He told her if marriage was what they wanted, they could do it tomorrow. It wasn’t her ideal proposal. A fight ensued. Both parties went to bed angry. The next morning Kat found Falls “in the happiest mood, and he’d made a list of the hundred people to be invited to our wedding. He’d picked our wedding song. He’d picked the singer who was going to sing it, and he wanted to chat about details,” she recalls. “I said, ‘What happened?'” Falls responded, “I had to get used to the idea.” Kat continues: “Then he told me something that’s been true ever since. He said, ‘I always like status quo in my life. It always really makes me happy, and every change is going to come from you.'”

In other words, a reverse universe from his life in theatre. Kat acknowledges as much, but she says that Falls prefers to put “all of his thought and energy into his work.” At home, he devotes early mornings to the children, cooking their breakfast, supervising piano practice, and getting them ready for school before heading off to the theatre. He returns for the bedtime ritual. Kat, now 42, has had several screenplays optioned and is currently writing a novel for young adults.

Kat finds her husband “incredibly intuitive” and teases him that he could have been a carnival psychic because “he completely reads people’s energy.” She claims he can sense everything “from negative neurotic energy” to whether a person “has father issues” or “alcohol problems.” The ability is intimidating, Kat admits.

It may also be what makes Falls a good director.

When it comes to selecting a production, Fall s works in two ways. “Either I like to think about a play for years and years and years, and finally it bubbles up as needing to be done now,” he explains. “The rehearsal process, then, for me, is an exploration of why. Or there are wonderful times where I like getting a phone call saying, ‘ Would you like to direct a play in three months? Here’s a new play.’ And that’s absolutely fantastic.”

Death of a Salesman represents the first way. Falls initially read it when he was 12. “It was one of the first plays that really went to my heart and overwhelmed me,” he recalls. “Of course, that’s because I identified completely with Biff Loman. I identified with the son. And by the time I directed it [in 1998], I was a father and my identification was solely with Willy Loman.”

Falls wasn’t the only one wrestling with the piece. “Arthur Miller spent his entire life trying to understand Death of a Salesman, because he wrote the first act in a burst over 12 hours,” says Falls . “When I worked with him on the 50th-anniversary revival, he saw new things. The play had changed for him, and you were aware that he was thinking at all times and trying to figure out what it meant 50 years later.”

The more serendipitous way of landing a show came about, for example, in 1999 when his old college buddy Stuart Oken, who had taken over as the executive vice president of Disney’s theatrical division, was having a hard time with the Elton John–Tim Rice musical Aida. Oken asked Falls to fix the “troubled show.”

|

Photography: Betsy Falls

|

| With his wife, Kat, and their children (from left), Declan, Connor, and Vivienne, recently in Long Boat Key, Florida |

Mary Zimmerman, who joined the Goodman’s artistic collective in 1992, was struck by Falls’s fearlessness in taking on the project-his confidence “in dealing with all those Hollywood types,” and his “sense that it’s OK to make something broad and spectacular.”

Falls’s framing device of having Aida start and end in a modern museum saved the show, Oken says. But it didn’t win over the critics. Aida’ s Cadillac Palace début met with mixed to negative reviews, Oken recalls. He says that he saw it as a tryout and suggested that they get back to work. Falls was “stung and healing and he let me have it,” Oken says. “I was being insensitive to how much it hurt.” Ultimately there was a happy ending. “We turned it around and took it from a show that was in trouble to a show that won four Tony Awards and has made a lot of money for the company,” says Oken. “Bob found the spine of the love story and made the show work.”

Still, it is safe to say that the experience didn’t alter Falls ‘s opinion of critics. “It’s a rather worthless breed of individuals,” he says. “I think they should completely go away. It would be a healthier community if there were no critics because, I think, it’s just one person’s opinion and I think that they achieve too much power.”

But isn’t it a critic’s job to express an opinion? “Critics are entitled to their opinion, but for the most part, I find critics not very bright, not particularly attuned to work,” Falls says. “There are those who create and then there are those who write about it. And I think that there is a huge difference between those two individuals.”

|

Photography: Chicago Tribune File Photo |

|

Rehearsing In the Belly of the Beast with William Petersen in 1985 |

During the Falls era, The Good man has flouri shed, as highlighted by the theatre’s 2000 move from space next to the Art Institute of Chicago to its current $46-million home at Randolph and Dearborn. “We were lucky. He’s led the institution to a national place,” says Lew Manilow. “What’s major, when you look at a 20-year span, is not just its duration but the fact that he took it from A to Z.”

The numbers bear this out. During Falls ‘s tenure, 207 shows have been produced on the Goodman’s stages. Of those, nine went to Broadway, four of them directed by Falls . Another 11, including three Falls productions, ran on Off-Broadway stages. Of the more than 50 world premières during Falls ‘s 20 years, he directed eight.

The theatre has more than 23,000 subscribers. Sales revenue has grown from $2.5 million in 1986 to $8.5 million this year. In the same period, individual and corporate contributions have jumped from $1.5 million to $5.6 million. (The executive director, Roche Schulfer, who has been at the Goodman for more than 30 years, also deserves credit.) In 2003, the Goodman was cited as the number-one regional theatre in the United States by Time, just over a decade after it earned the 1992 Tony Award for outstanding regional theatre.

Falls also takes pride in the Goodman’s diversity. He has nurtured talents such as Mary Zimmerman and the playwright Rebecca Gilman, whose latest star turn was last season’s Dollhouse, her update of the Henrik Ibsen classic, directed by Falls . “Bob is not at all afraid to bring in someone who might be better than him,” Zimmerman notes.

His artistic collective now includes the directors Henry Godinez, a cofounder of Teatro Vista, who oversees the Goodman’s biennial Latino Theatre Festival; Chuck Smith, long an important presence on Chicago’s African American theatre scene; and Regina Taylor, a TV star and playwright whose Dreams of Sarah Breedlove ran earlier this summer. This has resulted in more diverse works and an impressive growth in audiences of color.

Falls says his chief these days is his in ability to showcase the edgy material that more accurately reflects his tastes. “Ulti- mately, the artistic director’s job is to lead the audience and to present work to the audience that is challenging and provoc- ative,” Falls says. “The Goodman audience is really smart and really up to being challenged, but I also know that there are certain works that are just not appropriate.”

Hedy Weiss, the Chicago Sun-Times’ s theatre critic, loves some of Falls’s work but, like others in the theatre world, wants him to take more risks. “Now, because it’s the regional downtown anchor that produces basically 24/7, I think it maybe consciously or unconsciously feels the pressure to get bodies in the seats,” she says. In contrast to the strong identity that kick-started the Falls years, Weiss says, the Goodman today “often feels like programming by committee.” She would like to see it figure out the balance between the main stage and the smaller studio, which would allow that second space to live up to its potential as being “more flexible, more risk taking.”

A Chicago theatre veteran who has worked with Falls offers a slightly different critique. This veteran, who asked to remain anonymous because the theatre community here is “a small town,” considers Falls “brilliant” and “the greatest PR man I’ve

ever met. He talks a fabulous game.” But this vet goes on to say that Falls relies too much on the technical crews-the people who design the sets, costumes, and lights-to get him through a play. “He puts a veneer on the play and doesn’t get to the heart of the matter.” One example the source cites is Falls ‘s 1988 production of Landscape of

the Body, by John Guare. “He didn’t delve into the life and motivations of [the main female character], so consequently we didn’t get the play,” the vet explains. “We just got a surface reading.”

Still, this vet credits Falls with putting the Goodman on the map. Richard Christiansen agrees. Falls has made the Goodman “a major factor in resident theatres in the United States,” says Christiansen, whose 2004 book, A Theater of Our Own, drew on more than 40 years of following stage work here. “He did it by virtue of his own talent in producing shows and certainly in directing them.”

|

Photography: Courtesy Of Ralph Amelio |

|

Starring as Willy Loman in a high-school production of Death of a Salesman |

That talent should be on dis play in Lear, this year’s season opener. Falls and his leading man, Stacy Keach, have spent the past eight months e-mailing and talking about the elusive king and his multilayered drama. “It’s a play that communicates on multiple levels,” says Keach, who was the bastard Edmund to Lee J. Cobb’s 1968 Lear at Lincoln Center. “There’s always more. There’s always flux. There’s always change.”

Falls decided to set the play in modern times, connecting it to events in the post–World War II Balkans. “I’m not eager for people to reduce the play to a Balkan Lear, ” he says. He knows some will bristle at this reading, but he thinks the connection to the region’s history will spawn images that will illuminate the drama. “On a larger sociopolitical landscape, Lear, to me, can be read as a sort of parallel story of what happened to the larger Yugoslavia, what happened to Romania,” Falls explains. “That area saw very powerful figures in [Nicolae] Ceausescu or [Josip Broz] Tito, and then it saw a complete madness into despair and civil war and death.”

Keach, who is well regarded in the world of classical theatre but is most familiar to TV viewers for his starring role in Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer and as the warden in Prison Break, initially bristled at this modern reading. Eventually, Keach says, he decided that Lear resonates with “that kind of a tyrant whose appetite for power is only equaled by his appetite for attention and [his] vanity. ‘Who loves me the most?’ is the whole trigger for this play.”

Falls believes that Shakespeare, and especially his tragedies, are best served in contemporary settings. “I’m much more interested, for example, in what Peter Sel-lars did with Merchant of Venice, ” Falls explains, “which says this is a relentlessly modern play that tells us what it is like to be alive today.”

That means merging the seasoned art ist with the brash young director. ” King Lear will have a lot more maturity than my Hamlet did,” Falls says. “There’s no way that it can ever have as much youth or crazy energy as that Hamlet had, because I’m a different person.”

A month before rehearsals begin, Falls says his research helped him understand the play and justify his modern take. “I hope and think it will help audiences see the play in a fresh way and, to some extent, in a political way that’s larger than a play about this man and his daughter,” he says, “because I think it’s both-a domestic story and a great, large political story.”