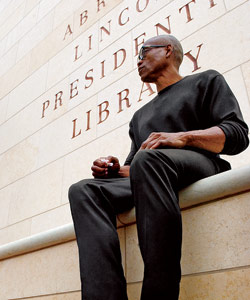

Bill T. Jones is not given to entertaining frivolous questions. Once, a reporter asked Jones—who bumps around a Rockland County, New York, house when he’s not in Manhattan creating avant-garde dance—which he liked better, the Mets or Yankees. “Neither,” he snapped. “I hate baseball.” Let’s put it another way: The New York Times didn’t call Jones, 57, the “political lion of modern dance” because he choreographs steps for sugarplum fairies.

Happily for Jones, heavy questions aplenty came with his newest project, Fondly Do We Hope . . . Fervently Do We Pray, which debuts at the Ravinia Festival on September 17th. The full-evening dance work, about the life and legacy of Abraham Lincoln, “is trying to talk about the questions that always confront a democratic society and definitely confront us now,” Jones says. “What is equality? What does a government owe us? Think gay marriage. Illegal immigrants. There is a great deal of uncertainty right now about these questions.”

A lithe six feet tall, Jones cuts a memorable presence. On winning Best Choreography for Spring Awakening at the 2007 Tony Awards, he joyfully ignored the stairs and vaulted himself onto the stage for his trophy. Last year, rave reviews showered his Off Broadway musical Fela!, about the musician and Nigerian political activist Fela Anikulapo Kuti. Many of Jones’s past dances have been defiantly abstract, audience-be-damned works that even he has called “excessive.” His Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land had local volunteers at tour stops appearing naked on stage; his raw 1994 work Still/Here showed video of people with terminal illnesses. Says Jones, laughing: “I was not lying around thinking about Abraham Lincoln, just dying to make a piece about him.”

Photograph by Peter Hapak

Jones won a Tony for his choreography for Spring Awakening

Someone else was: Welz Kauffman, the boyishly exuberant president and CEO of Ravinia. He wanted to commission a new work to cap off the festival’s summer-long Lincoln bicentennial celebration, which included the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s performance of Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait and an original piece by the jazz musician Ramsey Lewis.

A new dance seemed right for Ravinia, with its rich legacy of commissioning work from luminaries such as Ruth Page. “Bill T. Jones was at the top of my list,” Kauffman says. “I felt he had the right combination of artistic temperament and quality. . . . He seemed like the right person to take on the complexities of all that Lincoln is.” When Kauffman flew to New York three years ago to present the idea, the choreographer’s reaction—at least internally, as Jones recalls—was, “Oh, my God, what?” Worried Kauffman might want some Disneyesque biopic complete with stovepipe hats, his response was reserved. (Kauffman’s take on the meeting? “I remember [his] staff sort of tittering,” he says.)

Kauffman flew back to Chicago without a commitment, but not before giving Jones a copy of the Lincoln book by Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals. Soon, Jones says, he realized that while he’d never considered tackling the Great Emancipator, “I should have thought of it—because much of my work has been trying to understand justice and my dilemma as an American, as a black person, as a gay person.”

Lincoln’s promise of freedom for all, and the century it took before the United States enacted the 1964 Civil Rights Act, were clear entry points for Jones. A child of migrant fieldworkers, he was three years old when his parents left Florida and its Jim Crow laws to settle in upstate New York. His grandmother’s mother was a slave, and in Jones’s household the 16th president loomed as a mythic hero. “Lincoln was the only white man I was allowed to love unconditionally,” he says in a documentary by Kartemquin Films, to be aired next year on PBS’s American Masters series.

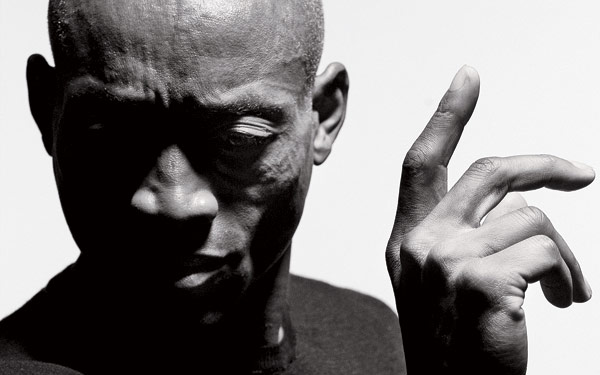

Attending SUNY Binghamton on a football scholarship, he quickly fell in love with dance—and with a white man: a Jewish student, Arnie Zane. They spent the next two decades together and in 1982 formed the still thriving Harlem-based Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. To Jones, their inability to marry legally represents one of many ways Lincoln’s vision for a country of equality has failed. (Zane died in Jones’s arms in 1988, from complications of AIDS.) “I come from the sixties generation,” he says, “and we were all ‘free at last, free at last.’ I believed it, at every level. But why has it been so difficult?” Much of Fondly Do We Hope . . . Fervently Do We Pray is Jones expressing, if not reconciling, the views of Lincoln he had as a boy and as a midlife liberal cynic—one who, he has said, “has very few heroes.”

* * *

Photograph: Paul Kolnik

|

|

Yet with age comes wisdom, too. This experimentalist, whom The New Yorker once chided for the “victim art” of Still/Here and its dying subjects, has wisely created a multimedia extravaganza that actually entertains. “I’m aiming for a broad audience,” Jones says. The challenge of engaging the Ravinia crowd in Lincoln’s story has the former dancer projecting text and video onto massive white-curtain panels; using lighthearted storytelling by two actors; and employing music ranging from that inspired by Mendelssohn to American folk, along with recitations from Shakespeare, Walt Whitman, and Lincoln’s speeches.

“Don’t be afraid to be corny,” said Bjorn Amelan, his partner and collaborator, during a debate about an opening that Jones worried was “too Star Trek.” The end result is a multilayered production of dance and theatre. “I would like people to walk away looking at each other, maybe smiling,” Jones says. “I would like parents and children to have a lively discussion, and people of different races to talk.”

Ultimately, though, the dance—which will travel to 13 cities in its first year of touring and, likely, to Europe and Japan—is personal to Jones. “I’m leading with the heart,” he warns. Born in 1952—“two years before Brown v. Board of Education,” as he likes to point out—Jones is looking back at America’s 19th century from 2009, and he is wise enough to admit that he doesn’t have it all figured out. Quoting a friend, he says, “A good leader doesn’t have to have all the answers, but a good leader should know how to ask the right questions.”

GO: Fondly Do We Hope . . . Fervently Do We Pray runs Sept. 17th and 19th at RAVINIA, 200 Ravinia Park Rd., Highland Park; 847–266–5100, Ravinia.org

Photograph: Russell Jenkins