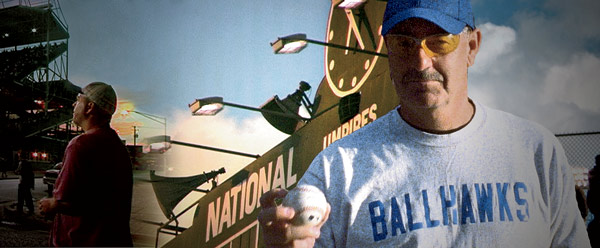

A montage of stills from the film

They’re as much a part of the Wrigley Field experience as the ivy inside the park: the half a dozen or so ballhawks camped along Waveland Avenue, waiting for home runs to emerge. In the new documentary Ballhawks, the first-time producer/director Mike Diedrich gives the aging athletes the Ken Burns treatment and captures the devotion that exists at the fringe of the game.

What makes the project stand out is the participation of the actor-brothers Joel and Bill Murray. It wasn’t the first Cubs film that had been pitched to the Wilmette natives, says Joel, who signed on as an executive producer. “People will say, ‘I’ve written this script, and you would be so great as the equipment manager.’ And then I find out they want me to get my brother Bill so he can play the lead.” This time Joel was the one who suggested that his older brother contribute to Diedrich’s film. “It was kind of a pipe dream,” says the younger Murray, 47, who is based in L.A. and recently appeared as a regular on the TV show Mad Men. “It’s hard to get Billy to do anything. He can get away like nobody I’ve ever met.”

The elder Murray has become Hollywood’s most sought-after white whale. He eschews agents and publicists, so most filmmakers must contact him via an 800 number that he may or may not check. Sofia Coppola spent months pursuing him for Lost in Translation. And once he agreed to star, she didn’t hear from the former SNL standout until he showed up on set.

Unlike Coppola, Diedrich, 50, hadn’t crafted his movie around Bill Murray. He wasn’t keen on using a narrator at all. “There had been so many Cubs films done with celebrity voice-overs, that was the last thing I wanted to do,” he says over beers at Murphy’s during a Cubs loss. “I just wanted to make a good movie. I didn’t have to have Bill.”

Diedrich wanted the ballhawks—proud fanatics who work the night shift to accommodate day games and track stats to increase their chances of shagging homers—to be the stars. He became fascinated with their dedication (some have been at it for decades) and how ballhawking kept these aging athletes connected with the game they love.

In 2006, while whittling down 300-plus hours of footage (shot mostly over the 2004 and 2005 seasons), Diedrich met Joel Murray. “He sent me a rough cut, and I thought it was unlike anything else out there,” recalls Joel. Over time, Diedrich grew excited by the prospect of scoring Bill, too, partly because the ballhawks recall his character in Caddyshack. “They’re borderline nuts,” explains Diedrich. “But they’re following their dream.”

Bill agreed to narrate in 2009, but it almost didn’t happen. Joel had packed up recording equipment and driven to his brother’s home in San Diego, but when he arrived, he was missing a necessary adapter. A few weeks later, he wrangled Bill into a suite at the Sunset Tower Hotel in West Hollywood and recorded the audio in just a few takes. The result is a deadpan, wounded-dog narration that elevates the material and captures the magic—and disappointment—of the Cubs. “He just went to a place from his own memories,” says Joel.

“[Bill Murray] brought the funny part out of it, but the movie also runs the scale of emotions,” adds Rich Buhrke, 64, a ballhawk with more than 3,400 baseballs to his credit. In the movie, he nearly chokes up talking about a catch. “He brought a passion to it.”

GO: BALLHAWKS screens September 11th at 7 p.m. at the Music Box Theatre, 3733 N. Southport Ave.; 773-871-6604, musicboxtheatre.com.

Photography: (Left) Courtesy of Andrew Dryer, (right) Courtesy of Mike Diedrich