Not so long ago, in a galaxy not so far away, when Chicago made its bid for the 2016 Summer Olympics, much of the conversation focused on potential negatives: It would cost too much. It would be too disruptive—detrimental, even—to certain communities. It would be a humongous economic loser, not a boon.

The city, of course, lost the bid, but the reaction was less one of relief than of indignant surprise. (Many Chicagoans didn’t want the games, but they didn’t want Chicago to come in dead last, either.) Which is kind of the opposite of how things have gone so far with the city’s bid for the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, the future home to a massive collection of art and film artifacts from Star Wars director George Lucas, expected to open in 2018.

After getting past the initial shock that Lucas actually picked Chicago, all sorts of critics came out of the woodwork to voice their objections: It’s just a vanity project. We don’t need a whole museum about Star Wars. We don’t know what will be in it, except it probably won’t be very good, merely second-rate movie props. Outraged lakefront preservationists quickly played the Daniel Burnham card—a private museum by the lake, they said, will sully Burnham’s grand vision of a vast, open lakefront park. Open space advocates have vowed to sue to block the project.

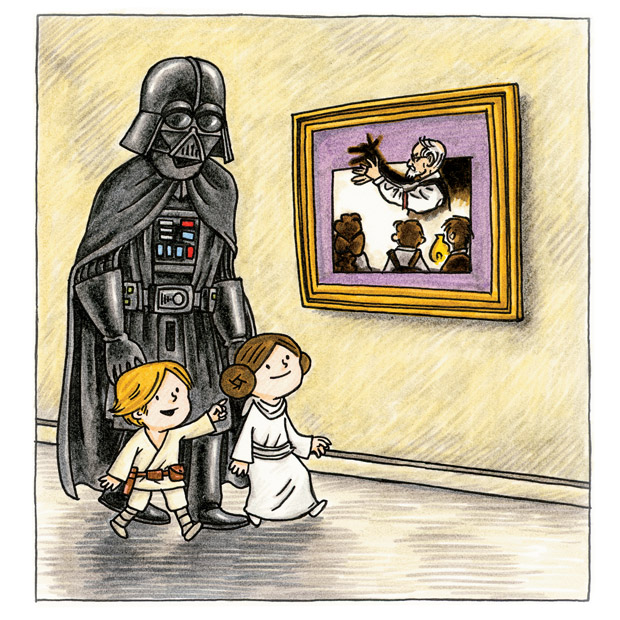

I admit I’m a bit biased in my hopes for the museum. I’ve spent much of the past few years writing and drawing Star Wars books, and I’ve been a lifelong fan of the films—and the comics, the toys, the trading cards, pretty much anything with a picture of Yoda or an Ewok on it. I still like Star Wars, and I make narrative art for a living. It would be dishonest of me to say I’m not hoping some of my own artwork will end up in this museum one day. Lucasfilm, after all, owns the original art from my first Star Wars book, Darth Vader and Son.

While I was working on that book, J. W. Rinzler, my editor at Lucasfilm, invited me to visit Skywalker Ranch, the holy land of Star Wars, nestled in the mountains just north of San Francisco, where a good deal of the work on Lucas’s films was done. Except for the gift shop, the place doesn’t exactly hit you over the head with Star Wars. Walking around the campus, I was expecting to see movie props and models everywhere, but there was just one small display of material, in the main house: a lightsaber, a tiny X-Wing model, maybe Indiana Jones’s hat.

Mostly, I was awestruck by other things: the stunning paintings and drawings from artists such as Norman Rockwell, Maxfield Parrish, and Arthur Rackham and the huge original canvas posters from classic films. Inside and out, the architecture and design looked unassuming and seamless. There were state-of-the-art sound studios; a beautiful private theatre; a two-story research library with a stained glass dome ceiling. It felt inspiring not just because it was where Star Wars was made but because it was a shrine, so to speak, to the creative process in many different forms: art, sound, cinema. I wish I could remember more about everything I saw, but I was constantly distracted by my 10-year-old self’s interior monologue: Oh my gosh, I’m at Skywalker Ranch, oh my gosh, oh my gosh, oh my gosh!

I also visited the Lucasfilm Presidio campus, which is where most of the company’s employees are now based. It’s also where a lot of the Star Wars memorabilia and art are kept—props, rare merchandise, production artwork. Not just for Star Wars but for other films, too: E.T. in Elliott’s bike basket and a background matte painting from Die Hard 2, among other items. But still, it was a lot of Star Wars—life-size Boba Fett and Darth Vader mannequins, Star Destroyer models, Han Solo’s blaster. (My 10-year-old self was even more distracted here than at the ranch.)

One of the first things I drew as a kid was Star Wars. It wasn’t just watching the films that inspired me; it was seeing the production art—the detailed storyboards and imaginative concept drawings by Joe Johnston, Ralph McQuarrie, and Nilo Rodis-Jamero. They inspired me as much as any works or objects at the Art Institute and the Field Museum, even if they’ll never get the same kind of cultural respect. It’s exciting to think about the kind of inspiration Lucas’s museum could give to people, particularly kids.

In the past, both the Field and the Museum of Science and Industry have hosted Star Wars exhibits, in fact. You can be cynical and say these were just cheap ways to boost attendance or that they were shameless advertisements for the film franchise. Or you can think about the 10-year-old kid who will visit the new museum and go home determined to make her own art, to rewrite the rules of whatever medium she chooses to work in, the way George Lucas changed the way films are made.

This will not be, as catchy as it may be to say, the “Star Wars Museum.” It’s a museum of narrative art, which encompasses much more than a single film franchise. From storybook illustrations to comics, pictures that tell stories have a history that dates back to cave painting. We’ve found meaning and understood the world better through narrative art, both in looking at it and, for some, in making it. It’s the art I made when I was growing up, the art I make now, and the art I most go back to reflecting upon.

Other than the fact that a renowned Chinese architect named Ma Yansong and Jeanne Gang were picked to design the building and the surrounding landscape, there haven’t been a lot of details about this museum—what’s in it, who will pay for it, who would own it, what it will look like—so speculation runs wild, the way it did each time we were waiting for the next Star Wars film. It’s good to question the specifics, but it seems silly to be starting with an assumption that whatever this museum is going to be, it’ll be bad. If there’s going to be a place on the lakefront that will spark creativity and capture the imagination, isn’t that a whole lot better than another parking lot?