Dapper for summer in a seersucker blazer, Alderman Walter Burnett Jr. stood onstage at a Garfield Park elementary school in July and touted his ward’s newest plum: the Hatchery, a kitchen space for chefs and bakers who can’t afford their own storefronts. Sitting behind him was Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

“A lot of things are happening on the West Side,” Burnett told a crowd of neighborhood residents and food industry professionals, listing two new parks, training centers for the Bulls and Blackhawks, and 482 new homes on the site of the old Cabrini-Green housing project. “We’ve been very blessed in our journey with this mayor to get things done. When I say this mayor is my partner, I call him my Hebrew homie.”

If Burnett comes off like a sycophant, even by the groveling standards of the Chicago City Council, it doesn’t bother him. As he put it after the event, “I get everything I want. Why wouldn’t I [support the mayor?]”

These days, a lot of West and South Side aldermen are getting everything they want, as Emanuel tries to buy back the goodwill he lost in the black community after the city stalled the release of the Laquan McDonald police shooting video. The mayor’s citywide approval rating bottomed out at 38 percent in May 2016; among black residents, it was an abysmal 30 percent.

In response, notes LeAlan M. Jones, a Bronzeville resident and political activist who was the Green Party candidate for the U.S. Senate in 2010, “he’s increased his posturing on the South Side.” Since the beginning of 2016, Emanuel has bestowed a cornucopia of civic projects on predominantly black neighborhoods. The city is building a police and fire training academy in West Garfield Park; the Department of Fleet and Facility Management’s garage, now on the North Branch of the Chicago River, is moving to Englewood. The $4 million Neighborhood Opportunity Fund and the $16 million Retail Thrive Zones program, both established since 2016, distribute rehab grants to small businesses on the South and West Sides.

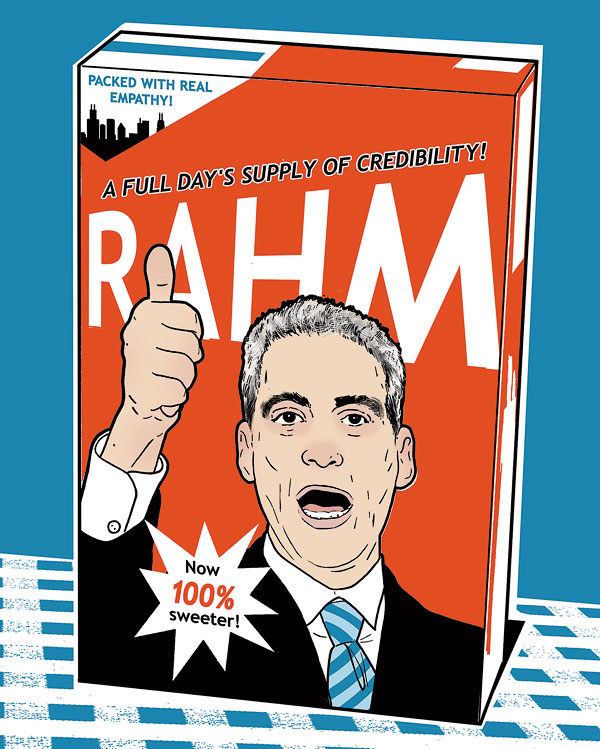

And as he did with his infamous sweater campaign ad, Emanuel is also looking for ways to soften his image (in his public duties, the mayor still appears as vindictive and humorless as Michael Corleone), not just with black voters but with the entire city. To show a different side, he started a podcast in June. On Chicago Stories, he conducts interviews with the mellow affect of an NPR host. One of his first guests was Harold Green, a South Side performance poet who read his “Something to Live For” at the mayor’s 2015 inauguration and recently invited Emanuel to speak at his FFTL Father’s Day Dance Party at the Promontory in Hyde Park. The two men mostly discussed their children. The podcast is “off the cuff, it’s organic, it’s real,” Green says. “It’s the ‘let my guard down’ mayor that I know. That’s the guy I’ve become fond of.”

Nice Guy Rahm also made an appearance on the Lakefront Trail at 39th Street to dedicate the first stretch divided into separate paths for runners and cyclists (a project paid for by Emanuel’s biggest donor, billionaire investor Ken Griffin). Spotting South Side resident David Olaoye biking toward downtown, he power-walked over to cheerily tell him, “You’re the first on our new bike-and-run separation.” Also on hand was Alderman Sophia King, who is dazzled by the mayor’s generosity these days: Her ward, which includes parts of Bronzeville and Kenwood, is getting the South Side’s first official dog park, an arts and recreation center in Ellis Park, and a new pedestrian bridge across Lake Shore Drive at 31st Street. “I was teasing the mayor,” King says, “he’s going to have to officially move here because he’s been cutting so many ribbons.”

But can the mayor buy back the goodwill of black Chicagoans? Amara Enyia, a Near West Side public policy consultant, says Emanuel was no friend to the community during his first term. She believes that after closing 50 schools, mostly on the South and West Sides, he only had his conscience awakened by political necessity. Between the 2011 and 2015 primaries, his share of the vote dropped from 63 percent to 48 percent in the 27th Ward, which includes East Garfield Park, and from 59 percent to 44 percent in the 4th Ward, which covers Douglas. That loss of support from black voters was the difference between an outright win and a humiliating runoff against no-name Chuy Garcia. And that was before the McDonald cover-up came to light.

“It shouldn’t have taken a teenager getting shot to invest in the neighborhoods,” says Enyia, who ran against Rahm in 2015 as an independent. “Everything he does is seen with a jaundiced eye [by the black community]: ‘You’re doing it because you need the black vote.’ ”

Emanuel has always been more dependent on, and solicitous of, the black community than his predecessor, Richard M. Daley, who was kept in power by a coalition of white and Latino voters. Emanuel’s coalition is white and black—but in the end it might not matter that he relies so heavily on black support. The only black politician who could beat him, Cook County Board president Toni Preckwinkle, insists she doesn’t want to be mayor. Cook County sheriff Tom Dart might be able to compete for the black vote, but he doesn’t have as much money as Emanuel.

“For all his negatives, he’s the favorite to win at this time,” WGN political analyst Paul Lisnek says of Emanuel. “The Laquan McDonald video situation should have been the end of any chance at reelection, but by 2019, that event will be four years away. Voters have short memories.” Emanuel’s approval rating is above 40 percent now, Lisnek points out. And there’s still more than a year to go before the primary—which leaves plenty of time for announcing more parks, small-business initiatives, and podcasts. “He’s a savvy politician who is doing what he can do to make Chicagoans feel he has their interests in mind,” Lisnek says.

By releasing the McDonald video when he did, Emanuel chose the perfect moment for his popularity to hit rock bottom: right after an election, with three and a half years to prepare for the next one.

Rahm’s Summer of Sweetness

July 3:Talked up the reliability of the CTA in The New York Times

July 8:Hammed it up with Jon Stewart at the Warrior Games at Soldier Field

July 13:Posed with a pintsize Radio Flyer for the local company’s centennial

July 15:Split a papaya salad in Pilsen with Steve Dolinsky for a “Hungry Hound” segment on ABC-7

July 30:Cut a green ribbon on a new affordable housing complex in East Garfield Park (paid for with $1 million in TIF funds)