On August 17, 2000, under a full moon, New York’s Lincoln Center was taken over by extraterrestrials — Lunarians, to be exact.

That day, more than 200 performers flocked to the sprawling performing arts complex to take part in The Lunar Opera: Deep Listening For_Tunes, a seven-hour interactive performance imagined by the American composer Pauline Oliveros. Participants came from all corners of the world to embody alter egos from “Lunarus,” a fictional moon nation, welcoming passerby to join in the performance. Per Oliveros’s instructions, the prima donnas and uomos came dressed as they pleased, whether bewigged, begowned, or bedazzled. “All the world was on stage,” Paul Griffiths wrote in his New York Times review.

Walk through that space today, nearly 20 years later, and you might still feel like you’re on another planet. Amid the coronavirus outbreak, the Lincoln Center, normally the pulsing heart of America’s performing arts, stands deserted, shuttered along with the rest of the world’s cultural institutions.

Now, like so many other artforms, opera is adapting. On Tuesday night, performing arts institutions in Chicago and Los Angeles will sponsor Full Pink Moon, a production of The Lunar Opera, in the unlikeliest of venues: a Zoom video conference. It will be the opera’s first large-scale public performance since 2000.

Created by composer–director Sean Griffin, Full Pink Moon is a joint venture between the University of Chicago’s Gray Center, CalArts, and Opera Povera, the experimental company Griffin directs. Like its predecessor, Full Pink Moon will draw participants from all over the globe: More than 250 artists representing a dozen-plus countries are currently slated to participate. The show will be streamed live for six hours, beginning at 8 p.m. CT, to audiences on YouTube, Twitch, Facebook Live, and the hosting organizations’ websites.

The stream is free, but Full Pink Moon is soliciting donations to Equal Sound’s Corona Relief Fund, which supports musicians who have lost income because of the COVID-19 outbreak, and to Opera Povera to compensate its all-volunteer creative team.

“I’m used to taking two or three years for an opera, and this is more like two or three weeks,” Griffin says. “We’re not getting a lot of sleep.”

When Griffin first put out feelers about the project over Facebook a few weeks ago, Gray Center director Seth Brodsky was eager to help, footing the bill for tech support, equipment, and other miscellaneous production costs. Full Pink Moon, he says, fits squarely with the Gray Center’s try-anything ethos.

“We were very supportive of this from the beginning, but we were also like, ‘I don’t know how this will work,’” Brodsky says. “It’s a cliche now, but experimental means, ‘Let’s try this out and see if it fails.’”

This isn’t Griffin’s first time working with the Gray Center. During a fellowship there in 2014, he co-created an an opera about the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, the seminal South Side music collective cofounded by Muhal Richard Abrams, which premiered at the MCA in 2015. (The same artists who performed in that opera, Afterword, will preface The Lunar Opera with a performance on the Zoom stream.)

.jpg)

The Center is also using Tuesday’s performance to inaugurate the Gray Sound Sessions, a streamed concert series that will feature solo and duo sets while Illinois shelters-in-place.

“We were sitting on a bunch of events that can no longer happen in the next few months, and we’re not an organization that plans things out hugely in advance,” Brodsky says. “Basically, we had the means to think about what else we might do in this particular moment.”

The Lunar Opera’s composer, Oliveros, who died in 2016, is embraced in experimental music circles for her philosophy of “deep listening,” a practice which challenges performers to expand their aural perception during music-making — for example, honing in on the oft-ignored respiration of an AC system, or the whir of a far-off highway. Oliveros did so with evocative, open-ended scores, many of which don’t include a lick of musical notation and read more like a series of directions. The score to Lunar Opera reads, in its entirety:

Each performer creates their own character with costume and props.

A performance area is designated.

Each performer decides on what sound to listen for and when the sound is perceived it is the cue to perform. The same sound or another sound can be used to stop performing and freeze until the cue comes again.

Each performer is responsible for their own character, costume, props and what or how to perform in response to the chosen cue.

For The Lunar Opera’s performance at the Lincoln Center in 2000, Oliveros’s creative and life partner Ione, a New York–based author and playwright, schemed a scenario involving the moon nation Lunarus, whose denizens hail from different cities, speak different languages, and possess different physical attributes. (Full Pink Moon won’t reuse that scenario, leaving the opera even more open to participants’ interpretation: Per the score, performers are simply tasked to invent some character for the six-hour duration.)

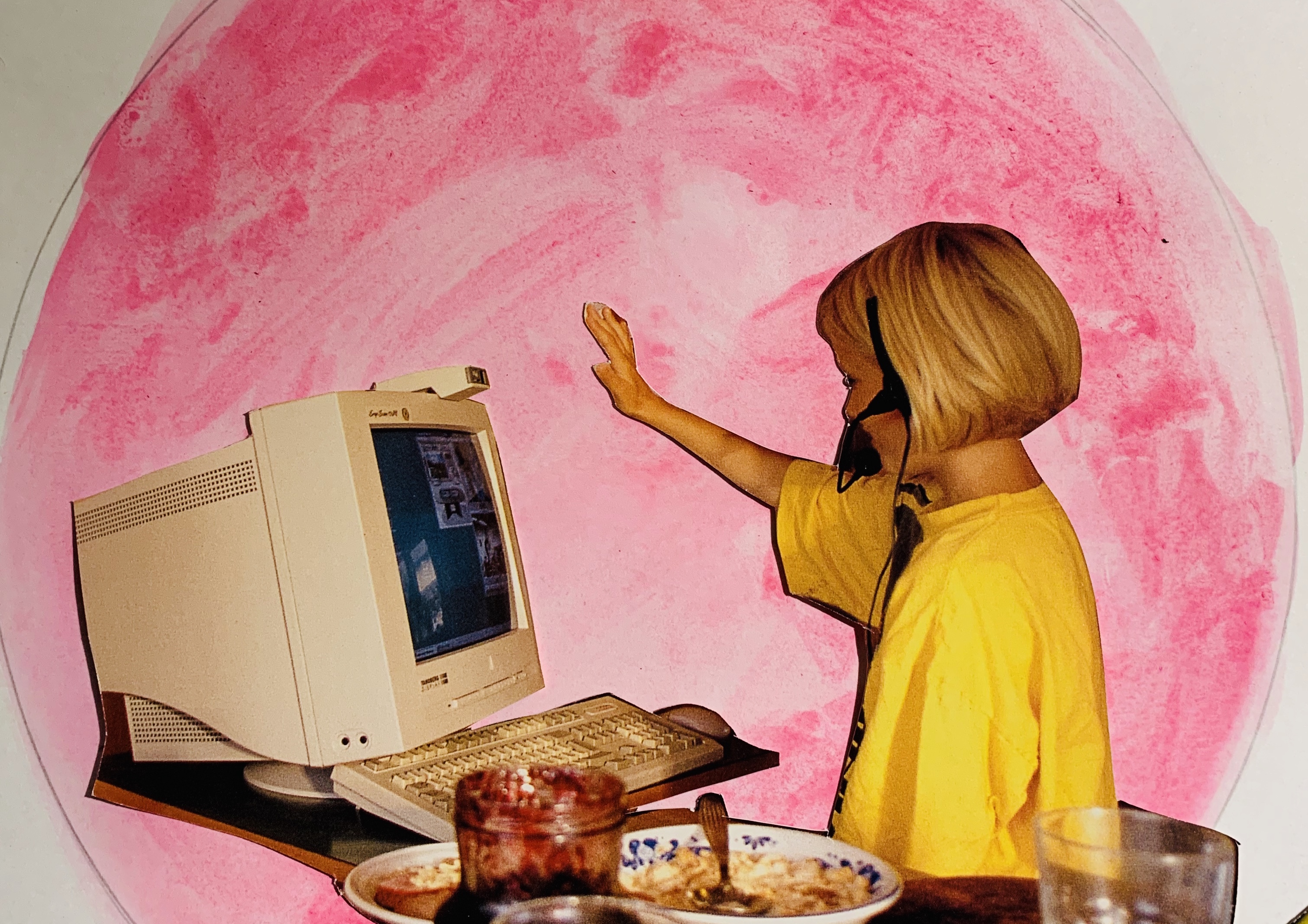

Photo: Nancy Beckman

The 2000 production came together almost entirely over email, a then-novelty which resonates with the technophilia of Griffin’s Zoom production. She and Oliveros kept a wide network of friends and collaborators abreast of performance logistics via lengthy email chains.

“It was a different way of realizing, ‘Oh, yeah, you can do this with hundreds of people,’” Ione recalls. “It was a brave new world.”

Griffin first encountered Oliveros’s work as a student at CalArts, eventually collaborating with her on an opera in 2012. Griffin and Oliveros never realized a Lunar Opera production together, but when he saw that the year’s biggest supermoon would rise on April 7 — a date when most of the world is remaining under self-isolation — he seized on the opportunity.

“[Oliveros’s] work is so benevolent. It requires a kind of creative commitment that’s deceptively simple,” Griffin says.

Not so simple are the logistics of a six-hour, hundred-performer Zoom call. To break up the opera, Griffin is splitting the show into three acts separated by creative interludes: The second act includes a fashion show, plus host-led “cocktail parties” interspersed throughout the opera. Most critically, performers are free to come and go as they please.

Griffin will also sort performers into “breakout rooms” — smaller micro-chats within Zoom — allowing them to engage with fewer people at once. However, the score doesn’t technically stipulate that performers take their cues from one another. Those stimuli can be anything from a sound in the Zoomosphere to something in their own spaces — say, the steady arrival of a bus outside or a phone buzzing. In fact, Oliveros’s score is so open-ended that it doesn’t even require all participants be musicians.

“We’re hoping to get movers and performance artists,” Griffin says. “I have some poets in Mexico coming in.”

There’s a pointed irony to a piece so tied to physical congregation finding new life in a disembodied video stream. But Ione suggests Full Pink Moon’s digital venue underscores what’s most essential to The Lunar Opera: uniting artists from around the globe, under the same full moon.

“I find its occurrence in this over-distance manner to be really connected with our vision for the piece,” she says. “Pauline and I always talked about doing it again.”

Full Pink Moon streams at 8 p.m. CT with a preconcert talk at 7. You can watch it here.