Samira Ahmed was 8 years old when the seed for her debut young-adult novel was planted. She was sitting in the backseat of her parents’ car, stuck in traffic on a day trip to Chicago, when a man in the car next to hers rolled down the window and yelled, “Go home you goddamned fucking Iranian!”

“I was frozen,” says Ahmed, who is Indian-American. Her 8-year-old self responded by trying to rationalize the man’s behavior. “I just figured racists are really bad at geography,” she says.

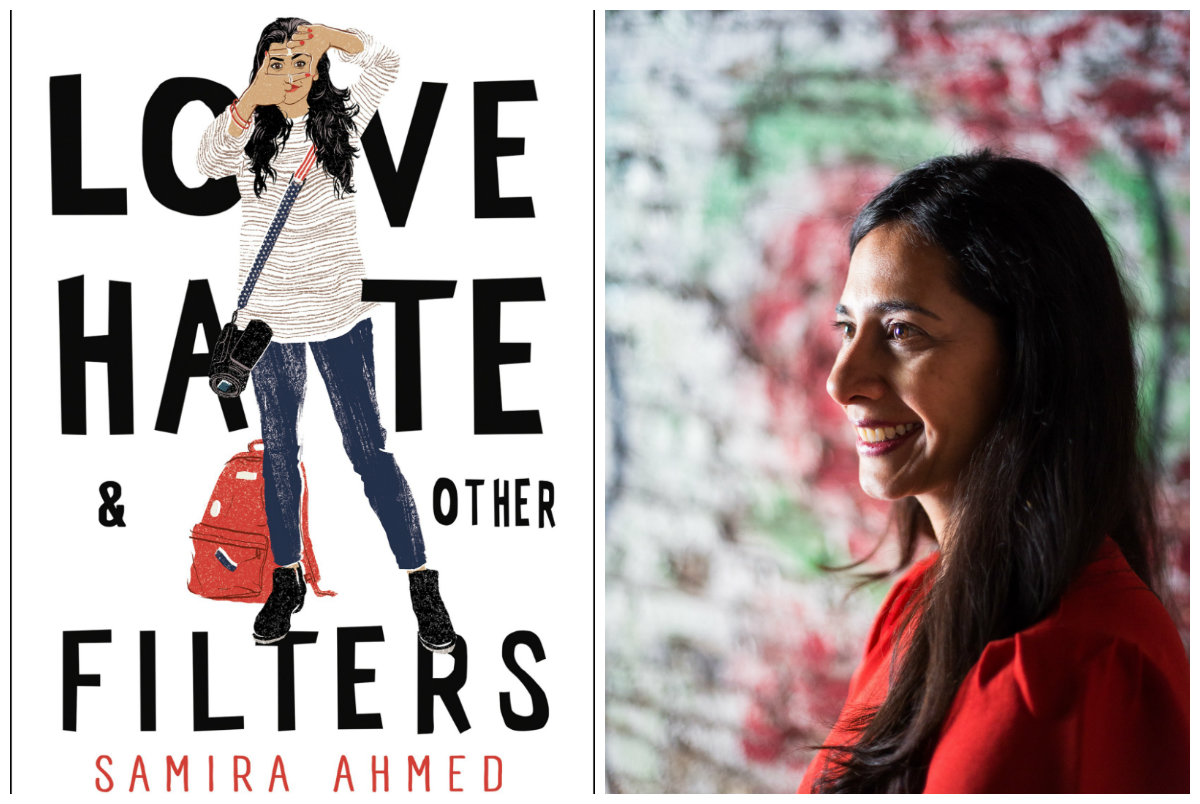

That encounter and others like it eventually spurred Love, Hate & Other Filters, which was published by Soho Teen last week. The Hyde Park resident’s book, which made it onto the New York Times Best Seller list for YA books in its second week, comes at a time when major publishing houses are finally picking up books by people of color that tell complex stories about race and prejudice. Last year, Cicero native Erika Sanchez’s I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter was shortlisted for a National Book Award and Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, which grapples with police violence against black teenagers, spent weeks atop the Times's YA Best Seller list.

Ahmed’s encounter with racism as a child, coupled with reading about an incident in New York City where a cab driver was assaulted by a passenger who thought the driver was Muslim, drove her to capture the moment when a young person first confronts overt racism. “Nothing prepares you for that,” she says. “Suddenly you realize the world looks at you in a way you never expected.”

The novel, which Ahmed spent seven years (on and off) writing, follows Maya Aziz, a high school senior and aspiring documentary filmmaker living in Batavia, the Chicago suburb where Ahmed grew up. When an act of domestic terror hits Springfield—perpetrated by someone whose name is also Aziz—Maya must navigate the wave of Islamophobia that passes through her hometown. “I wanted to show how hatred can really change lives,” Ahmed says, “how it can affect the individual and the community in which we live.”

In shaping Maya’s story, Ahmed mined her own experiences. Though Ahmed recalls a happy childhood in “Norman Rockwell–esque” Batavia, it was far from perfect. "It was then and is still a predominantly white town," she says. "I was the only South Asian—and I think the only Muslim—in my graduating class.”

In the book, Maya finds a handful of allies in Batavia, while others in the town “take the [Muslim] part of her identity and choose to make her an other because of it,” Ahmed says. For example, after the attack in Springfield, a classmate asks Maya if her uncle carried it out, and someone throws a brick through her the window of her parents’ clinic. Ahmed also weaves in her experiences teaching high school in Chicago, where many of her students were recent immigrants.

More than 30 years later, Ahmed's encounter in the car is still crystallized in her memory. “A little bit of your childhood is shattered when you’re confronted with something like Islamophobia or racism in such an overt way,” she says. Living in Trump’s America hasn’t helped. “Seeing someone call your nations of origin ‘shithole countries,’ can really be so cutting,” she says. “A lot of times kids can draw into themselves.”

Ahmed hopes the book will speak to both kids and adults who are confronting prejudice by helping them see that they’re not alone. “Despite the odds, they have people cheering them on, and I hope they can persist," she says. "Because that’s what Maya does."