No writer has ever captured a city the way Gwendolyn Brooks captured Chicago. Beginning with her debut poetry collection in 1945, A Street in Bronzeville, she illustrated the beauty and hardships of African-American life on the South Side. Her muse was the Bronzeville neighborhood—the hypersegregated center of Chicago’s Black Belt—for the first half of her life, thanks to institutionalized racism like redlining and restrictive housing covenants.

But after the Harlem Renaissance petered out in the 1930s, Bronzeville became the cultural hub of Black America just as Gwendolyn Brooks reached adulthood. Within a few blocks of today’s 47th Street Green Line station, modern blues, jazz, gospel, and a new brand of literary realism were born, kindling the careers of Nat King Cole, Lorraine Hansberry, Louis Armstrong, Richard Wright, and Brooks herself.

Today would have been Gwendolyn Brooks’s 100th birthday, so we revisited her most frequent haunts in Bronzeville to see how they’ve changed.

47th and South Park

From the age of two until she graduated from college, Brooks lived a few blocks north of the heart of Depression-era Bronzeville: the intersection of 47th Street and South Park Way (now Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive). Between 1928 and 1970, this was the site of the Regal Theater, a lush nightclub, music venue, and movie theater twice the size of the Apollo. During its heyday, the Regal drew performers like Cab Calloway, Nat King Cole, Sam Cooke, and Louis Armstrong. As a young adult in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Gwendolyn Brooks went to the Regal with her mother and brother to watch movies. She liked the romance films starring Bette Davis, Clark Gable, and Katharine Hepburn, while her brother preferred westerns. In the longest poem from A Street in Bronzeville, Satin-Legs Smith frequents the Regal to “boo the heroine / Whose ivory and yellow it is sin / For his eye to eat of.”

The Regal was demolished in 1973 and replaced with the Harold Washington Cultural Center, a modern performance venue and event space. Initially shrouded in scandal thanks to the alleged nepotism and mismanagement of former alderman Dorothy Tillman, it was supposed to be the centerpiece of a tourist-friendly “blues district,” but that plan was abandoned. However, in recent years the venue has become an active hub for dance, poetry, and acting classes, according to the Chicago Defender.

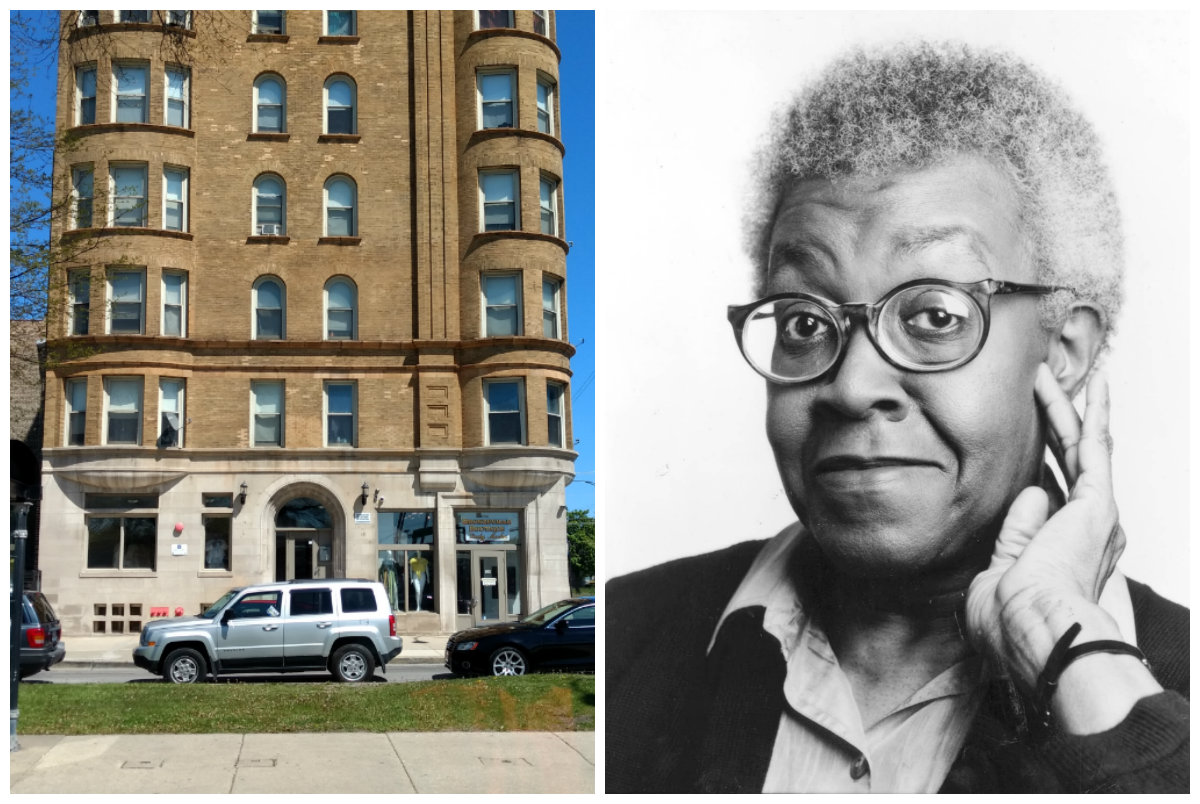

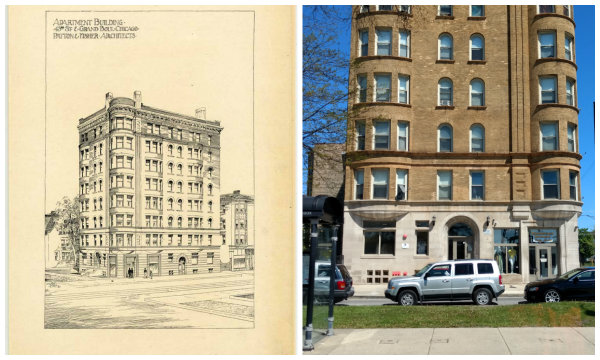

The First Kitchenette

One of Brooks's best poems, “kitchenette building,” evokes the cramped living quarters of many black Chicagoans between 1915 and 1950. White landlords, seeking to maximize profits during the Great Migration, carved up single-family apartments into two or three smaller units with paper-thin walls.

The first kitchenette that Brooks lived in still stands at 4259 South King Drive. “I remember feeling bleak when I was taken to my honeymoon home, the kitchenette apartment in the Tyson on 43rd and South Park,” she says in her first memoir, Report from Part One. Constructed in 1893 when the neighborhood was white and wealthy, the building was originally called the Belmonte Flats. When Brooks and her new husband Henry Blakely arrived in 1931, it had been carved up into kitchenettes and renamed the Tyson Apartments. Today the ground floor is home to the Bronzeville Boutique, while the upper floors remain residential.

The South Side Community Art Center

After her son was born in 1940, Brooks began taking poetry classes at the new South Side Community Art Center (3831 S. Michigan Ave.) with Inez Cunningham Stark, an editor at Poetry magazine. It was here that Brooks wrote and workshopped many of the poems in A Street in Bronzeville, and where a visiting Langston Hughes heard her perform “The Ballad of Pearl May Lee.”

According to Eleanor Roosevelt, the Georgian Revival-style brownstone was once the home of Charles Comiskey, founding owner of the White Sox. Today it’s still a vibrant center for the arts in Bronzeville, both as a museum of African-American art and as a meeting space for artistic youth and teens.

The Mecca

After publishing A Street in Bronzeville in 1945, Brooks became a national sensation. Five years later, she became the first black woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for her second collection, Annie Allen. By then she had left Bronzeville for Woodlawn, and later settled in the Greater Grand Crossing area for 40 years. But her writing never left Bronzeville behind, including her strongest indictment of Chicago’s racial injustice, the 1968 collection In the Mecca.

“The Mecca” refers to the Mecca Apartments—also known as the Mecca Flats—which was built as a hotel for world’s fair visitors in 1893. As the Bronzeville population swelled during the Great Migration, the Mecca was converted into crowded apartments for African Americans and left to rot. Conditions were so bad, it inspired the classic blues song “Mecca Flat Blues.”

Brooks never lived in the Mecca, but she did work there for a few months after college in the mid-1930s. It was probably the strangest job of her life: assistant to a spiritual adviser who lived in the building and was later murdered. “She would see herself toiling up the stairs to various ones of the 176 apartments to deliver ‘Holy Thunderbolts’ and ‘Liquid Love Charms’ to people whose lives were so often steeped in misery and violence,” writes George E. Kent in A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks.

The Mecca Apartments were demolished in 1951 by the Illinois Institute of Technology, who had hired Mies Van der Rohe to remake the northwestern corner of Bronzeville in his stark, modernist style. Today the corner of 34th and State is occupied by Van der Rohe’s S. R. Crown Hall, home of IIT’s College of Architecture. While not intentional, the building’s lines and symmetry echo the beautiful interior courtyards of the Mecca, which—like so many other icons of Bronzeville’s rich history—are now lost forever.