Mark Turcotte, the newly named poet laureate of Illinois, arrived in Chicago by accident. In 1992, Turcotte’s estranged father died in North Dakota. Father and son hadn’t had a relationship since Turcotte was a child. As he wrote in his poem “Father’s Dust”: “dust of lies,/ dust of rage,/ dust of wandering,/ dust of going away,/ then finally,/ the dust of never returning.” But Turcotte was his son, so he took it upon himself to bury the old man at the Turtle Mountain Chippewa reservation, and clean out his apartment in Fargo.

Turcotte drove back to Michigan, where he’d spent his childhood, intending to sort out his old man’s possessions there. On the way, he stopped in Chicago to visit an old high school English teacher. At the time, Turcotte was working on an oil exploration crew in west Texas. Knowing her old student was interested in poetry, the teacher thought he could do better than that. So she invited him to stay in Chicago and help her remodel the basement of her three-flat.

“It was a sneaky way to get me to stay in Chicago and get me to go to poetry readings,” Turcotte says.

Turcotte took immediately to the Chicago poetry scene of the 1990s, reading regularly at the Green Mill’s poetry slam and the Guild Complex in the Chopin Theatre.

“On any given night, you could read poetry on a stage,” he remembers. There wasn’t any money in poetry, so “I was hanging sheet rock by day and hanging out at poetry readings by night.”

That summer, Turcotte won the first Gwendolyn Brooks Open Mic Award — and began a fellowship with Illinois’ longest-serving poet laureate, who was then the godmother of Chicago poets, a “literary elder.” Although Turcotte was a newcomer to the state, Brooks named him a Significant Illinois Poet, invited him to read at Illinois Poet Laureate ceremonies, and wrote a blurb for his first collection, The Feathered Heart, praising its “[e]xciting energy and venturesomeness.”

“I would never dare say that Gwendolyn and I were friends or besties, but when I spent time with her, she was always encouraging,” Turcotte says of Brooks, who was the state’s poet laureate from 1968 until her death in 2000. “She was the model that I was able to witness. I was around in the ’90s when she was active. She wanted young people to feel as valued for being artists and writers as people are for being sports heroes.”

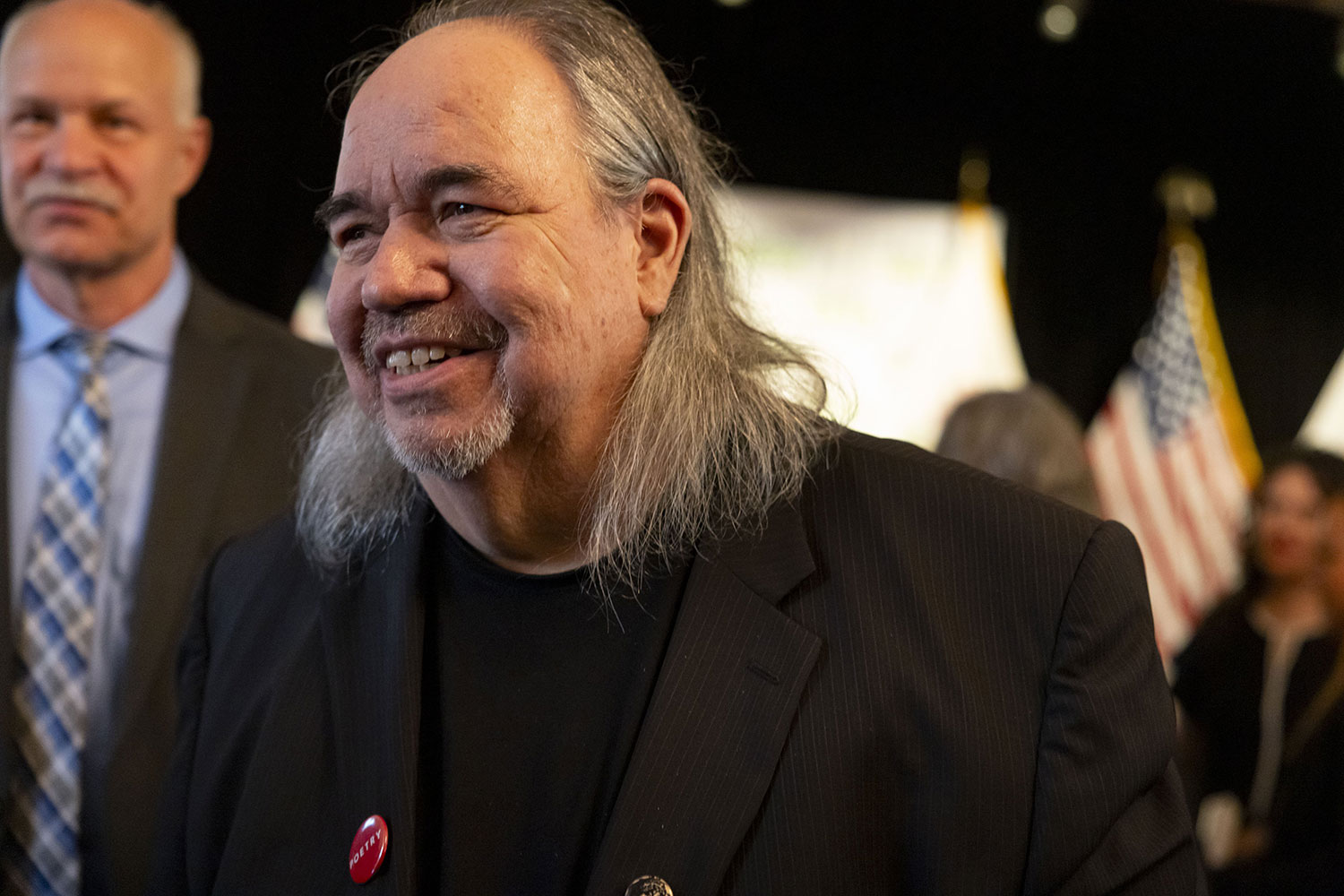

As the son of a Chippewa father, who spent time on the reservation as a child, much of Turcotte’s poetry concerns the Native experience. At 67, he wears what remains of his hair long, and he titled one of his collections Exploding Chippewas. Here’s an excerpt from his poem “Flies Buzzing”:

As a child I dancedto the heartful, savagerhythmof the Native, theAmerican Indian,in the Turtle Mountains,in the Round Hall,in the greasy light ofkerosene lamps.

As a child I dancedamong the long, jangle legs ofthe men, downbeside the whispering moccasin women,in close circlesaround the Old Ones,who sat at the drum,their heads tossed, backs archedin ancient prayer.

As poet laureate, one of Turcotte’s goals is to bring Native writers to Illinois, a state that lacks a significant Native presence, since it has no reservations. He cites Andrea Carlson’s “You Are On Potawatomi Land” Riverwalk mural as a local example of Native artistic activism.

“Illinois is one of those places, and the Chicago area, with a history that’s important to Native people, and it’s one of those states where everybody got moved out,” he says. “We always sort of get relegated to history. There are people who think there aren’t any Natives anymore.”

But Turcotte’s biggest challenge as poet laureate will be filling a position once held by Brooks and, before her, Carl Sandburg. Those were Pulitzer Prize-winning poets, with international reputations. Sandburg wrote “Chicago,” in which he coined the nickname “City of Big Shoulders.” Brooks’s use of street language made her a progenitor of hip hop. If you’re reading this article, it’s probably the first time you’ve heard of Mark Turcotte. Brooks had a lifetime appointment, but he’s only getting a four-year term. Poetry isn’t as big as it used to be, and neither are poets, but Turcotte is serious about the mission of bringing his art to young people. (Look for him at your local high school.)

Turcotte eventually quit his work as a handyman, because it was “ruining my body,” and now teaches at DePaul, where he is Senior Lecturer and Distinguished-Writer-In-Residence in the English Department.

“I’ve always had a day job,” Turcotte says. “I’ve never been that lucky as a writer. Part of it is that I’m a poet.”

The new gig comes with a $35,000 a year stipend, though. Maybe there is a little money in poetry, after all.