“We are in Chicago, but probably not the Chicago you’re thinking of,” writes Maggie Andersen in her new memoir, No Stars in Jefferson Park. Now a 47-year-old associate professor of English at Dominican University, Andersen grew up in Ravenswood, where she currently lives with her husband and son. But as the title indicates, much of the book is tethered to the neighborhood she describes as “a scrap of small-town Wisconsin or Michigan sewn into the patchwork of Chicago,” the place that spawned her first artistic home, The Gift Theatre.

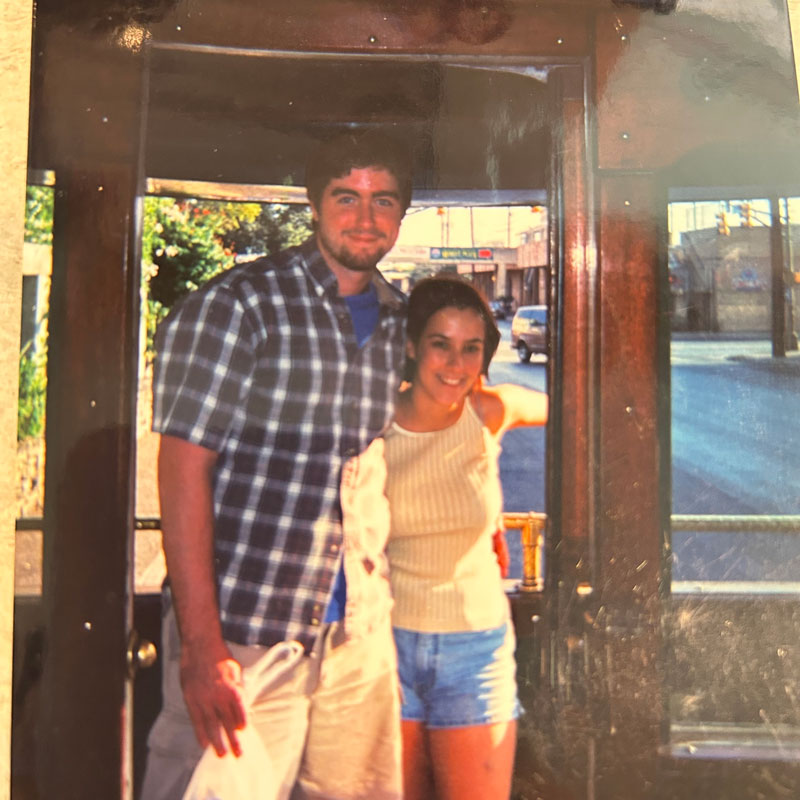

The far Northwest Side area is also the home to her ex-partner Michael Patrick Thornton, an acclaimed actor who, in 2001, founded the Gift Theatre with Andersen and a group of friends. But two years after the troupe began, on the day of the annual St. Patrick’s parade downtown, 24-year-old Thornton suffered a spinal stroke that left him reliant on a wheelchair.

No Stars chronicles that tumultuous time in their lives, pinging back and forth between two formative eras. One on hand, readers get an inside peek of the earliest days of the Gift, which found quick success — its first production was directed by the late, legendary Sheldon Patinkin (best known for his work with Second City and Steppenwolf). Meanwhile, readers follow Thornton’s journey, along with his parents and Andersen, through months of rehab and beyond.

The book’s various dramatic tensions include the challenges facing people with disabilities; Andersen’s choice to ultimately break up with Thornton, with whom she remains friends; and her soul searching about pursuing a writer’s life, which entailed leaving home for a few years to study at Western Michigan University under Chicago’s own MacArthur genius, Stuart Dybek. No Stars is Andersen’s first book; following its October 15 publish date, there’s a book-launch party October 28 at Steppenwolf, featuring a plethora of local theater artists plus an appearance by Dybek. Andersen discussed her writing process with Chicago.

Among the many stories you share in No Stars is your origin as a writer. We learn that you’ve been working on this book for nearly 20 years. Tell me about that journey.

Artists have such different trajectories. I mean, Mike [Michael Patrick Thornton] would’ve told you, since he was 5 years old, “I’m going to be a famous actor,” like some artists do. They have this self-knowledge and this kind of ambition at a very early age. But that is not the case with me. I always loved writing and theater. I was that dork who did poetry club and theater in high school, and I got a scholarship to UIC, where I was an English major and a theater minor, and I really, really loved both. Then Mike wanted to start this theater company, so I chose that route. How could I not, right? It was exciting. But even while I was in it, I had an awareness that was sometimes painful but instructional: I loved watching people who had been born to be on stage, and I knew that that wasn’t me.

When Mike was recovering and I was caring for him, I thought, something about me doesn’t want to act anymore. The thrill was gone in a lot of ways. Eventually I went to Western Michigan to study with Stuart Dybek, who is my favorite short-story writer. He told us about Amy Hempel, so I went and read her short story, “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried,” which is gorgeous. Stuart told us it came from a writing prompt: “Write the thing you’ll never live down.” So I then wrote a fictionalized short story about me and Mike. It was important to fictionalize it at that time, I think. The following year, I started to write this memoir. I wrote a lot of it in graduate school, between 2008 and 2012. I needed somewhere to put that grief, and then later, I tried to make it artful.

Reading your memoir made me really reflect on the art of the autobiography, I suppose partly because I grew up in Jefferson Park and Ravenswood, and I love Chicago theater, so many of the names and places in the book are familiar to me. While a lot of memoirs get written later in life, you’ve written yours at a much younger age. How did you navigate telling these very personal stories about other people, who are very much alive?

When I first sent it out for publication in 2012, I’m not sure I thought as much about these questions then. Mike had read it and he loved it, and we were both excited about it. An agent in New York tried to sell it for a few years, but it didn’t go — editors felt that Chicago theater was too tight of a platform, too niche. It was a bit of a heartbreak, but I had a toddler at home and I was still new at Dominican University, so I thought, “I should be focusing on other things.” I’m so glad it wasn’t published then, because it gave me time to think about these questions, which are really important. One thing about non-fiction is: If you’re going to get this personal, you better look at yourself as critically as you’re looking at everyone else.

Eventually, a decade or so later, it found a home with Northwestern University Press. Did you end up making many revisions?

I definitely did. I was able to see myself more clearly, so I tried to be hardest on myself, which was easier than when I first wrote it. I was able to see the ways in which I was at fault; I was able to see the ways I was a really annoying, insecure girlfriend. I was also able to see Mike’s mother, Rita, and her burdens more clearly, now that I’m a confident woman in my 40s.

When Megan Stielstra, Northwestern editor, put out the call that she was looking for Chicago and Midwestern stories, I thought, Should I take this manuscript out of the drawer? I wasn’t sure. The question you always have to ask about memoir: Who cares? The answers I came up with are: We need to tell more complicated stories about disability, and I think we need to open up conversations about caretakers. Especially in this moment where so many Americans are being stripped of their health care, it felt pretty urgent to me. What Mike went through was hell for him, and it was incredibly difficult for his caretakers, including me, but I was one of many. I can’t imagine what that experience would have been without good health care. The story also feels important because we’re slashing arts funding all over the country, and art really did — it sounds cliché — but art really did save both of us. It saved our sanity, so it’s important to tell a story about art.

What next for Maggie Andersen, the author? You have a second book in the works, correct?

Yes, it’s an essay collection about my family’s three-flat and all of the eccentric characters who have lived here over the years. It’s also very much about these two worlds that I feel I belong to in Chicago: the working class and the artist class. And Mike Thornton is not in it — when I told him that, he said, “Booo.”