Growing up lower middle-class in Chicago during the 1940s and ’50s, Michael Mann became acquainted at an early age with cops and crooks. They captured his boyhood imagination, dominating the front pages of newspapers that graced the kitchen table of Jack and Esther Mann’s family home in Humboldt Park and later Ravenswood. He read columns by Irv Kupcinet and Mike Royko that chronicled colorful figures like the Panczko brothers, a notorious trio of prolific thieves from the Northwest Side who came to be known as the Polish Robbin’ Hoods.

“You would be following what the Cubs were doing, what the White Sox were doing, and you also knew what [mob boss] Tony Accardo was doing,” the filmmaker said recently over the phone from his home in Los Angeles. “It was just part of the atmosphere in Chicago, the lore of the city.”

After decades in California, the 82-year-old director of The Last of the Mohicans, The Insider, and Collateral has not shed his neighborhood accent, and still refers to the city of his birth as “Chi-CAW-go.” He attended Amundsen High School, around the corner from the now-defunct Summerdale police station, where, in 1960, when Mann was a teen, Chicago police officers were implicated in a massive theft ring — one of the most stunning, high-profile scandals in the department’s history. “Cops were doing burglaries, hauling TVs and refrigerators away in paddy wagons,” Mann says. “There were some real dark sides to the city, big time.”

By the mid-’70s, Mann was cutting his teeth writing for television. He penned episodes of procedurals like Starsky and Hutch and Police Story while doing research for a screenplay that would become his first feature, Thief. He had grown tired of the old cops-and-robbers formula — heroes versus villains, never the twain shall meet — and burned to make work with a hard-edged authenticity.

That’s when a friend introduced him to a man by the name of Charles Adamson. Born and raised in Chicago, the hulking Adamson had been a member of an elite detective squad called the Criminal Intelligence Unit, whose objective was to gather information about the activities of habitual crooks. Ultimately, what Adamson would tell Mann was exactly the kind of story he was looking for: a riveting account of his own lethal cat-and-mouse game with a skilled, brazen thief in Chicago named Neil McCauley. These events would form the basis for the filmmaker’s masterful crime saga, Heat, which set the bar for modern action movies when it was released on this day 30 years ago.

Mann soon came to know Adamson as one of those cops for whom — to borrow a line from Heat — the action was the juice. Digging through historical newspaper archives, one gets a vivid sense of the detective’s crime-fighting derring-do, whether chasing down a thief on foot while dodging traffic on Lake Shore Drive or tailing a car full of burglars more than 700 miles beyond Chicago’s city limits. In Heat, LAPD detective Vincent Hanna (played by Al Pacino) tries to explain his obsessive pursuit of big-score criminals like Neil McCauley (portrayed by Robert De Niro), telling his wife, “All I am is what I’m going after.” There was more than a bit of Adamson in that single-mindedness.

“Charlie told me this anecdote about McCauley,” Mann says. “The CIU was surveilling McCauley’s crew and through an informant found out that they were going to hit a Wieboldt’s department store at night to get to the safe. This is when people got paid in cash, and they had a lot of cash around on that certain night. Charlie’s unit was laying on the score from outside and inside the building. McCauley had probably invested five, six weeks setting this thing up. But McCauley looked around and something intuitive sparked. There was one thing out of place on the outside of the store — one too many trucks in a parking lot or something — and he pulled his crew out and they didn’t do the burglary. They split and they never came back.”

That event would inform a sequence in Heat in which McCauley and his fellow thieves are on the verge of executing an intricately planned heist. That is until McCauley senses “the heat around the corner,” and calls it off. “What struck me about this story was that McCauley’s act of discipline and professionalism really impressed Charlie,” Mann says. “He regarded McCauley with a kind of respect, because of how disciplined he was and what kind of a high-line pro he was, and he wanted to know all about him.”

By pure accident Adamson would get his chance to pick McCauley’s brain. One day in Lincoln Park, Mann says, “Charlie was dropping off his drycleaning, and coincidentally McCauley was there and they spotted each other. By this point, McCauley had figured out that the CIU was on him, and he wanted to know who they were and find out more about them. As Charlie told it, ‘My hand went to my gun, and then I’m looking across [at] this guy and said, Come on, I’ll buy you a cup of coffee.’” Their chance run-in would inform the famed diner scene in Heat, with De Niro and Pacino going toe-to-toe on screen for the first time — a major draw for audiences upon the film’s release.

Adamson and McCauley sat down with each other at a restaurant called Belden Corned Beef Center, later renamed the Belden Deli, at 2315 North Clark Street. “The purpose behind the meeting for Charlie was to feed his conscious and subconscious mind about who this person is,” Mann says, “so that intuitively, if it came down to it, in a millisecond, he might have to make a decision: Is McCauley going to zig or is he going to zag?”

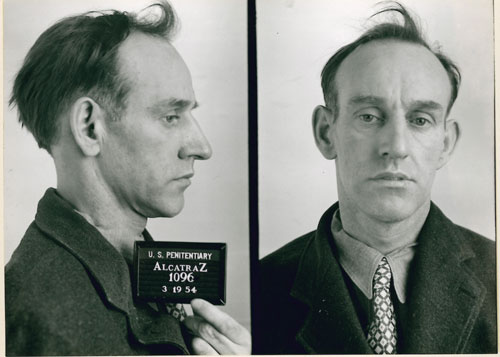

Over his career, McCauley had accrued a lengthy rap sheet, including a nine-year stretch at Alcatraz for the robbery of savings and loan associations. “I’m 41 now and I’ve spent almost 20 years of my life in jail,” he was quoted in the Chicago Tribune as saying on the eve of his Alcatraz bid. “I don’t have a family. As a matter of fact, I haven’t been out of jail long enough to meet a girl to marry.”

“For McCauley,” Mann says of the coffee shop tête-à-tête, “it was the same motivation. The more he knew about Charlie, the more he could protect himself. And so they got into how and why you are the way you are. But there was a rapport between them. It was a sense of, You’re a regular fella, which was a very Chicago expression for that period. Chuck was going through a disastrous marriage with a policewoman, the whole thing was blowing up at the time, and they wound up having an intimate conversation. At the same time Neil McCauley was something of a sociopath who’d kill you as soon as look at you, and Charlie Adamson wasn’t. It was the definition of a dialectic, in which there were some components that were the same and others that were diametrically opposed. Charlie spoke admiringly about McCauley, yet Charlie would not hesitate to blow McCauley out of his socks if it came to it.”

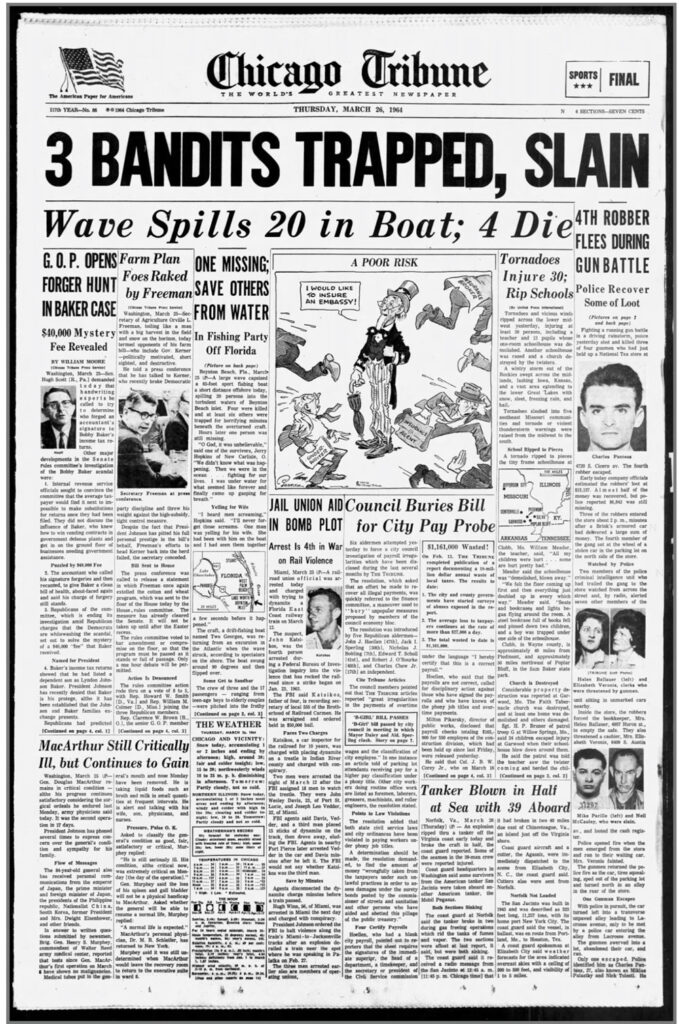

Their collision would finally take place on March 25, 1964. Around 2 p.m., McCauley and two members of his crew entered a National Tea grocery store at 4720 South Cicero Avenue a few blocks from Midway Airport, guns drawn, while a getaway driver idled in the parking lot. A Brink’s armored car had just made a substantial cash delivery.

The CIU had been surveilling McCauley’s gang for several weeks. Adamson and another detective followed them to the store and watched from across the street as the thieves looted the safe and cash register of more than $13,000. Several other members of the unit sat nearby in unmarked cars waiting for the radio signal to move in. Reading the news reports about that fateful day, it’s easy to understand the cinematic possibilities Mann sensed in the fierce gun battle that ensued.

“Police opened fire when the men emerged from the store and ran to their waiting car,” read the Tribune’s breathless front-page story. “The gunmen returned the police fire as the car, tires squealing, sped out of the parking lot and turned north in an alley in the rear of the store. With police in pursuit, the car turned left into a transverse unpaved alley leading to La Crosse Avenue, only to be met by a police car . . . . The gunmen swerved into a lot, abandoned their car, and ran.”

During the foot chase, Adamson caught up with McCauley in a gangway. Mann says McCauley raised his gun and pulled the trigger but it misfired, allowing Adamson to pump six bullets into his 49-year-old nemesis. The fatal encounter is reflected in the climactic final scene of Heat, when Hanna guns down McCauley after a tense nighttime pursuit set among the runways of Los Angeles International Airport.

After their initial meeting, Adamson and Mann grew to be close friends and collaborators. Adamson appeared as a detective in Mann’s Thief in 1981, alongside his former CPD partner Dennis Farina, who would soon trade in his badge for a Screen Actors Guild card; the film also featured professional thieves W.R. “Bill” Brown and John Santucci. “All of these guys had been chasing each other, and now they’re all working on this film,” Mann says, chuckling at the memory. “So it was a real slice of life.”

Mann mentored Adamson as a TV writer in the mid-’80s, and the ex-cop, who had by then relocated to Las Vegas, ended up penning four episodes of the Mann-produced sensation Miami Vice and co-created the gritty, serialized NBC drama Crime Story, another ahead-of-its-time Mann production. Adamson eventually retired to southern Oregon and passed away in 2008 at the age of 71. The following year, Mann dedicated his Chicago-shot John Dillinger film, Public Enemies, to his buddy Charlie.

All these years after Adamson planted the seed for what became Heat, the story continues to flourish in Mann’s life. In 2022, he released his first novel, Heat 2, a prequel-sequel co-written with Edgar Award–winning author Meg Gardiner. He’s currently developing a film adaptation that reports suggest could star Leonardo DiCaprio and Christian Bale. Early in the book, Mann brings the action back home to Chicago circa 1988, with Hanna working as a CPD detective as McCauley is in town robbing safe deposit boxes. This time, however, the two narrowly miss each other.