It was a golden era of indie labels. You couldn’t swing a dead cat in 1990s Chicago without hitting one that was defined by idiosyncratic interests and personalities, all dogged enough to make them viable. Touch and Go, Delmark, Alligator, Wax Trax!, Thrill Jockey, Drag City, Minty Fresh, Carrot Top, Johann’s Face, Atavistic, Pravda, Feel Good All Over, Kranky, and others were supporting original music. Some had stars in their eyes and future stars on their rosters. Others liked their buddy’s band and thought a few hundred others might as well. They followed their ears and their hearts; if their brains, some luck, and enough fans followed, so much the better. The pioneering spirit was everywhere. Anyone, we thought, could do it.

As this was happening, music and artists tarred with the “country” brush were unceremoniously consigned to the Not Interested piles at most indie labels. But taking refuge in the bars and clubs where local artists were dipping their country-curious toes into overlooked waters, we thought we were hearing music deserving of some sort of documentation. Seated along a bar rail in the winter of 1993, Old Styles in hand, we grabbed a napkin and quickly made a list of 15 to 20 names. What if, our last-call cogitation went, we brought together under one umbrella artists no one else was showing an interest in? What if — our eyes gleamed — we put them on a CD and released it ourselves? On our own label? It was a brilliant plan. Well, it was a plan, anyway. If nothing else, it might be a good way to cadge some guest-list spots and free drinks around town. It really was that simple, the motivation that genuine.

So it came to pass that Eric Babcock, Nan Warshaw, and I started a record label. We each ponied up $2,000 from our wretched day jobs or savings accounts and — poof — we were a label. Punk had taught me that I could act, so I should act. Thinking about the consequences would only slow us down. The worst that might happen was we’d be left with a pallet of unsold CDs, and I’d go back to repairing squeaky cat doors and painting over bloodstains in cruddy apartments. It was an unexpected turn of events, considering I had moved to Chicago a couple of years prior to get away from the music industry (I had been a stage manager in Detroit, among other roles) after a decade of finding in it kinship and identity, excitement and growth, culminating in burnout and dismay. But music will always surprise you if you let it.

With dewy-eyed zeal, the three of us spent the gloomy early months of 1994 approaching artists around town about giving us a song for our unnamed, untried idea that existed in a smoky, middle-earth space between abstraction and pipe dream. We sought out the kids left off the other teams, the Bad News Bears of the underground, the outsiders of the outsiders. We hung out at my apartment listening to records and cassette demos and going through the club listings in the Chicago Reader. We propositioned bands working the club circuit — the Riptones, the Texas Rubies, the first-wave bluegrass/punk/rockabilly outfit Moonshine Willy, and the New Duncan Imperials — that were somewhat established but not part of any identifiable “scene,” a few side projects, and a couple of groups that were never heard from again.

One night we listened to an LP by the Sundowners, the cowboy trio I had seen on one of my first trips to Chicago. It had this fantastic song on it, “Cigarette State,” a bluegrass-tinged raver with the snarky line of lines: Alabama’s grand / the state, not the band. There was respect for form but also totally bent content. Perfect. It was credited to one “Robert William Fulks.” We’d seen “Robbie Fulks” listed at clubs like Deja Vu and Lower Links — it had to be the same guy. We looked up “Fulks, Robert” in the phone book — this was a time when every apartment, no matter how ill furnished, had one lying around somewhere, even if to hold up the three-legged couch — and cold-called. Could we use the song? “Sure,” he said, “but I’ve got my own version.” The deal was sealed.

The Mekons’ Jon Langford, who had moved to the city a few years previous, walked into the original Empty Bottle, where a couple of us were busy at the bar, emptying bottles. We pitched him on participating. With his buccaneer spirit and keen eye for potential mischief, he was in. Within weeks, he delivered “Over the Cliff,” featuring Tony Maimone — the bassist of heroes of my youth Pere Ubu — which etched a sharp line from what we were doing with the label back to what had helped get me there in the first place.

The Handsome Family had given us a four-song demo cassette with a drawing of a raccoon on it and a note with the caveat that they weren’t very “good” yet and didn’t have a lot of material. But I was floored by “Moving Furniture Around,” a song squarely in our sought-for wheelhouse — timeless country pathos updated for an urban environment. With lyrics that had parking tickets and shitty landlords taking the place of coal mines and company stores, a distorted guitar rattling like a cold wind past the semi-abandoned furniture showrooms on Milwaukee Avenue, and a knack for deep-catalog Americana weirdness, they fused the malaise of Kristofferson with the simmering rage of the Pixies. I couldn’t wait to see them live. They had a show at Phyllis’ Musical Inn, one of Nelson Algren’s old Polish Broadway haunts, on an unfashionable stretch of Division Street. Past the well-used bar, with its dusty bottles of DeKuyper schnapps, was a “stage” wedged into the corner. Singer-guitarist Brett Sparks introduced himself and sheepishly told me they were going to suck — but, you know, enjoy the show.

I sat at the bar next to a red-haired guy who looked vaguely familiar from Lounge Ax shows. Once the Handsomes started, it was obvious that Brett wasn’t being self-deprecating; they really weren’t very good. Tempos changed mid-song, bass parts wandered off in different directions, and Brett was still learning how to effectively project his dark-as-a-dungeon voice. Ugh. Could I get out of this somehow? I was sitting eight feet from the stage, so it’d be tough to make a stealthy exit. Worse, the guy next to me, now a bit drunk, loved them and wasn’t bashful about expressing it. What a dummy, I thought. After the show, I paid vague compliments to the band, thanked them for the tape, and bolted. I’d use the song, but I didn’t think they had much of a future as a band.

Messed that one up, didn’t I? The Handsome Family spent the next 25 years putting out some of my favorite albums, exquisitely terrifying and beautiful, the way a decaying, mossy log or a half-awake-at-dawn nightmare can be. Turned out that superfan was the owner of another recently formed local label, Carrot Top Records. I think he signed them that night.

Freakwater and the Bottle Rockets were bands that had already released albums, so we regarded them as seasoned giants in this little field, and they said yes as well. It was a stretch to claim the Rockets as Chicagoans since only their bass player lived here, but fuck it — we were defining our parameters. Furthermore, they were on indie labels, Thrill Jockey and East Side Digital, that we looked at as role models. Having these “heavy hitters” on board, with their critical acclaim, outside-the-area-code tour histories, and “real label” support, might even lend credibility, if only through glancing association, to the project.

Finally, we thought a nod to Chicago’s country music history would provide a narrative arc for those who might think Chicago + Country = Absurd. We included two tracks from the Sundowners. Those guys had helped, unwittingly, coax me to Chicago in the first place, and now it was time to pay them back.

The bands we had gathered were glad someone — anyone — wanted to document what they were doing.

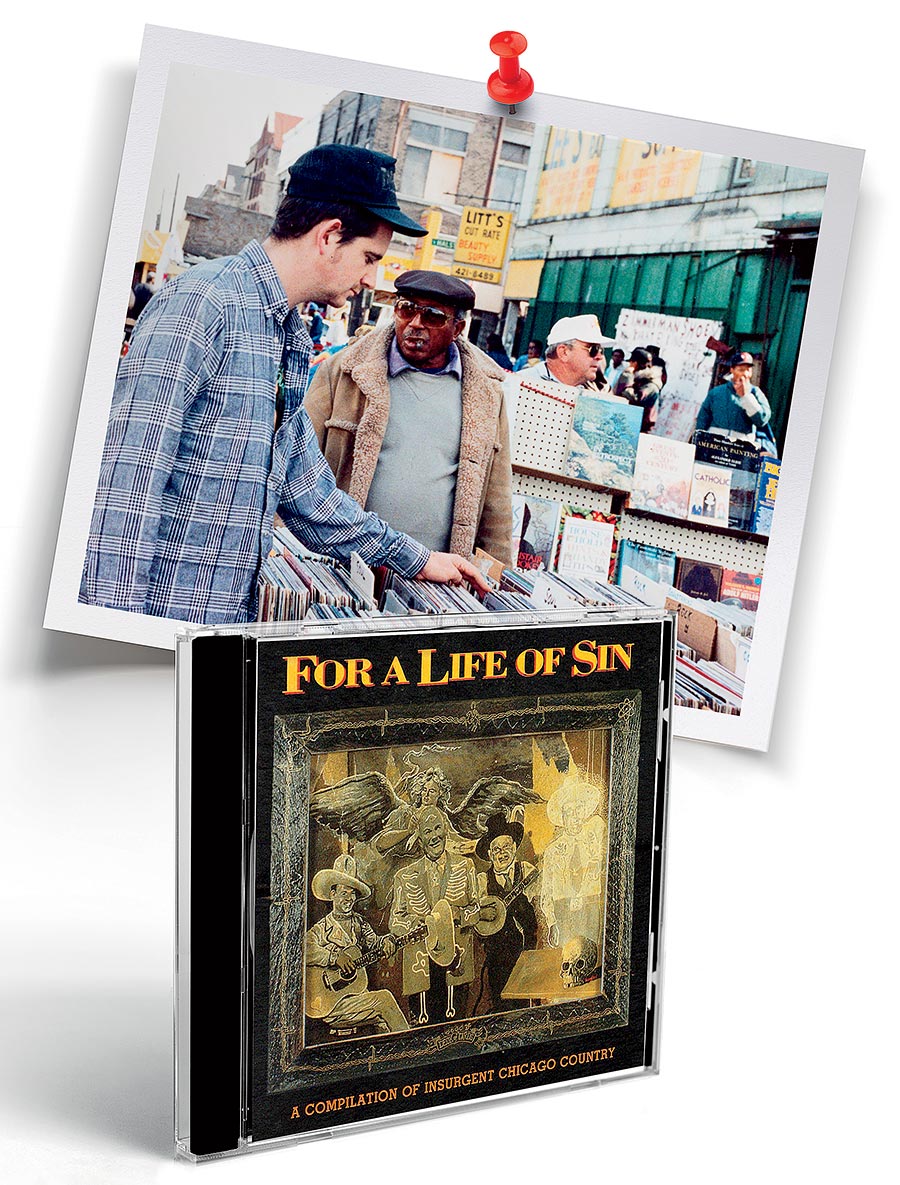

The album was mastered on the sly in a studio in the Harold Washington Library after days of beery debate over a sequence to find a flow, to tell a story in the era before shuffling and streaming. Jon Langford lent us a painting depicting ghostly country music figures, skulls, and a protecting angel for a cover that struck a balance between unsettling and classic, unorthodox and yet somehow familiar. For a main title, we cribbed “For a Life of Sin” from “Lost Highway,” the Hank Williams honky-tonk hymn I had first heard through a cover by a band of reckless Nashville punks, Jason & the Scorchers.

The bands we had gathered were glad someone — anyone — wanted to document what they were doing at that place in that time. There was no expectation of a career, no one was trying to “make it,” and no one, but no one, ran home, kicked open the back door, and dragged their S.O. into the boudoir, yelling victoriously, “Prepare for some sweet, sweet lovin’ because I’m on my way to the big time. I’ve been signed by …”

Oh right, we needed a name.

When asked the origin of “Bloodshot,” my go-to answer is that I looked in the mirror one morning and it was yawning back at me. And while a good one-liner is rooted in truth, there was more to it. We brainstormed on themes inherent to country and punk: hard living, rebellious streaks, quotidian hassles and humiliations, and the little guy getting screwed over. I was a fan of Wynonie Harris, the ’40s and ’50s blues shouter with too little malt shop rock and too much lascivious roll in him for the tastes of parents terrified of fledgling teenage culture and race mixing. His 1951 killer hangover song “Bloodshot Eyes” on King Records rattled around my head: Don’t roll those bloodshot eyes at me / I can tell you’ve been out on a spree.

“Bloodshot” it was. It sounded cowboy, but not hick, more renegade.

Since the rare critical language surrounding the melding of roots and punk was either discursive or dismissive, we wanted to plant our black flag and define our own message before someone else hung a horrendous tag on it. We took it for granted that launching this project into an underground rock environment using “country” as a broad characterization would have been outright idiocy. It was a loaded term that would elicit reflexive derision — like a movie description that began “Starring Pauly Shore” — from the very indie music followers, people like us, we thought would be most interested. The entire genre had been cast by many — for often good reasons — down an elevator shaft. We wanted a term that tapped into the kindred feelings of rebelliousness and candor that had drawn me to punk rock initially and that I was finding anew in this music.

And while it is a world of uncertainty and chaos, it is a truism that where there are English majors and beer, there will also be a thesaurus and dictionary nearby. We ran through words like “rebel,” “guerrilla,” “revolution,” and “malcontent” as I dug through the trusty Roget’s — until “insurgent” caught my eye. It had it all: conviction, purpose, and an antisocial, piratical flourish. Thus, a genre was coined: insurgent country. A British interviewer once commented that it sounded “a bit Woody Guthrie and a bit Sex Pistols.” I’m good with that.

Compilation compiled, we sent it off for the mysterious, faraway process of manufacturing. I went back to painting two-flats, drywalling a home office, stripping crown moldings in Old Town, West Town, wherever. And we waited.

What were we looking to accomplish in this city known for blues, industrial music, and razory-guitar indie rock? Maybe we’d sell the CDs. Maybe not. Maybe one day an eccentric Japanese or German completist would find a copy at the back of a used-record store and be thrilled the same way I was when I found a compilation on Detroit’s Fortune Records that had Skeets McDonald’s “Tattooed Lady” plus, it promised, “Eleven Other SIZZLERS” on it. The question, to the extent it was ever asked by either the artists or us, wasn’t “Why do this?” but “Why not?” I was so excited at the prospect of shining a light on this fluky little scene in Chicago that I doubt anyone could have talked me out of it.

In June 1994, a shipment of BS 001 For a Life of Sin: A Compilation of Insurgent Chicago Country CDs arrived at the “office” — the dining room table of one of the partners — and a new independent record label launched its first (and we thought last) album. No Champagne was popped, no “We’re on our way now” toasts were made. There was a name, a press release, and … now what? What did a label do? Even though Eric had worked at small local indie labels before, Nan had done some freelance promotion and publicity, and I had production writing, reviewing, and college DJ experience, the next step was new and unknown. Forty boxes of plastic discs stacked in the corner? It sure didn’t feel like the makings of moguldom, but it was something. We had made this.

Excerpted from The Hours Are Long, But the Pay Is Low: A Curious Life in Independent Music with permission of the University of Illinois Press. © 2025 by Rob Miller.