If you could mix the creative DNA of Dr. Seuss, M.C. Escher, and John Waters, you’d get something akin to Bruce Goff, the singular 20th-century architect. Giant metal ribs arching up from the ground, defining a patio space; cantilevered beams poking out emphatically from a roof; undulating staircases echoing the curves of a circular den: Goff never encountered a surprising shape or a bold color he didn’t embrace.

Although best known for his iconoclastic structures, he was also a painter of abstract art and a composer for the player piano — all part of the story told in Bruce Goff: Material Worlds, a major retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago running December 20 to March 29. “There’s no one person who’s doing all the same things as Goff. He really is marching to the beat of his own drum,” says AIC’s Alison Fisher, curator of architecture and design.

Born in 1904 and raised mostly in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Goff moved to Chicago at age 30 and spent eight formative early-career years here. Unlike his famous mentor Frank Lloyd Wright, whose structures are easy to identify, Goff did not craft a signature style. While the elder architect admired his imagination, Fisher notes, “Goff was a little bit too out there for Frank Lloyd Wright — but it was a warm and very important relationship for both architects.”

Indeed, comparing two very different homes Goff designed in the area illustrates both his range and his whimsy. He remodeled a modest wood-frame home in Uptown in 1947 for a recording engineer, transforming it into the Bachman House with dramatic peaks, triangular windows, and “a corrugated aluminum siding that makes it kind of look like a spaceship,” Fisher says. Two years later, in west suburban Aurora, he designed the Ford House, a split-level domed residence. Inspired by the Quonset huts he’d learned about while stationed at a naval base in Alaska during World War II, Goff made bold design choices, starting with distinctive red steel arches as the home’s skeleton. Inside, one wall is constructed from coal brick interspersed with green cullet glass, while other surfaces are covered with thick nautical rope. In 2023, the Department of the Interior deemed the house a National Historic Landmark.

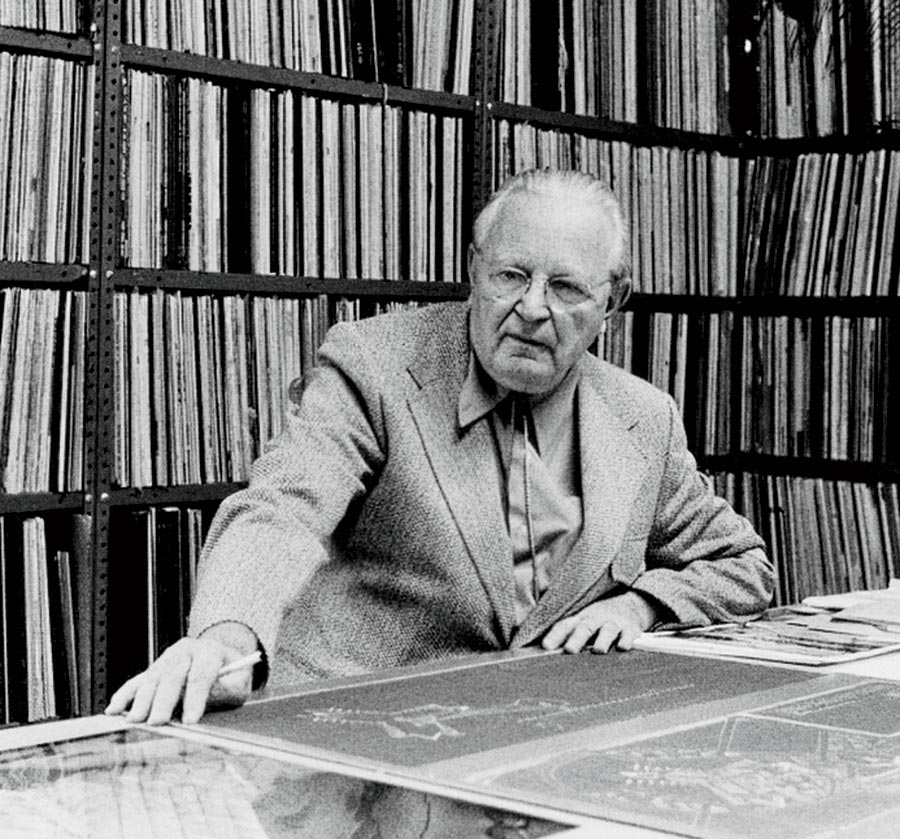

AIC holds a massive Goff archive, which it used to produce an exhibition in 1995 focused solely on his architecture. One of the curators of that show was Sidney K. Robinson, a UIC architect professor, now retired, who became the self-appointed steward of the Ford House when he bought it in 1986. Before he set foot inside it, he admits, “I thought Bruce Goff was a nut!”

The new exhibition will be distinctive from the one he worked on, Robinson says. For example, it delves into the fact that Goff was openly gay and shared a home in Rogers Park with the love of his life, the poet Richard San Jule, who died on New Year’s Day 1946. “Certainly Goff suffered in his own lifetime from his queerness,” Fisher observes — particularly in 1955, when he resigned from his position as head of the University of Oklahoma’s architecture school because of a related scandal. “We did not address his sexuality in ’95,” Robinson says. “It just shows you, 30 years is a long time.”

In Material Worlds, “the range of Goff’s playful imagination will be on display,” notes Robinson, who donated one of the show’s key elements: a three-panel folding screen that Goff had originally designed for the Bachman House but ended up in his possession. A mixed-media piece, it incorporates segments of a player-piano roll adorned with paint and metallic stickers. Says Fisher: “Because it’s a piece of furniture that also references music and has a painting component — the three areas where he did significant work — to us, it’s the Rosetta stone of Bruce Goff.”

Goff died in 1982, at 78; his remains were ultimately interred at Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery, also the final resting place of Burnham, Sullivan, Mies, and other giants of architecture and design. Unlike them, “he’s not a household name,” Fisher acknowledges — partly due to his indifference to consistent branding, which he eschewed in favor of always reaching for something new. He also designed hundreds of other structures, some quite fantastical, that were never built, and many of those plans are on view here. With Material Worlds, AIC seeks to boost Goff’s star into the upper firmament, where it belongs.