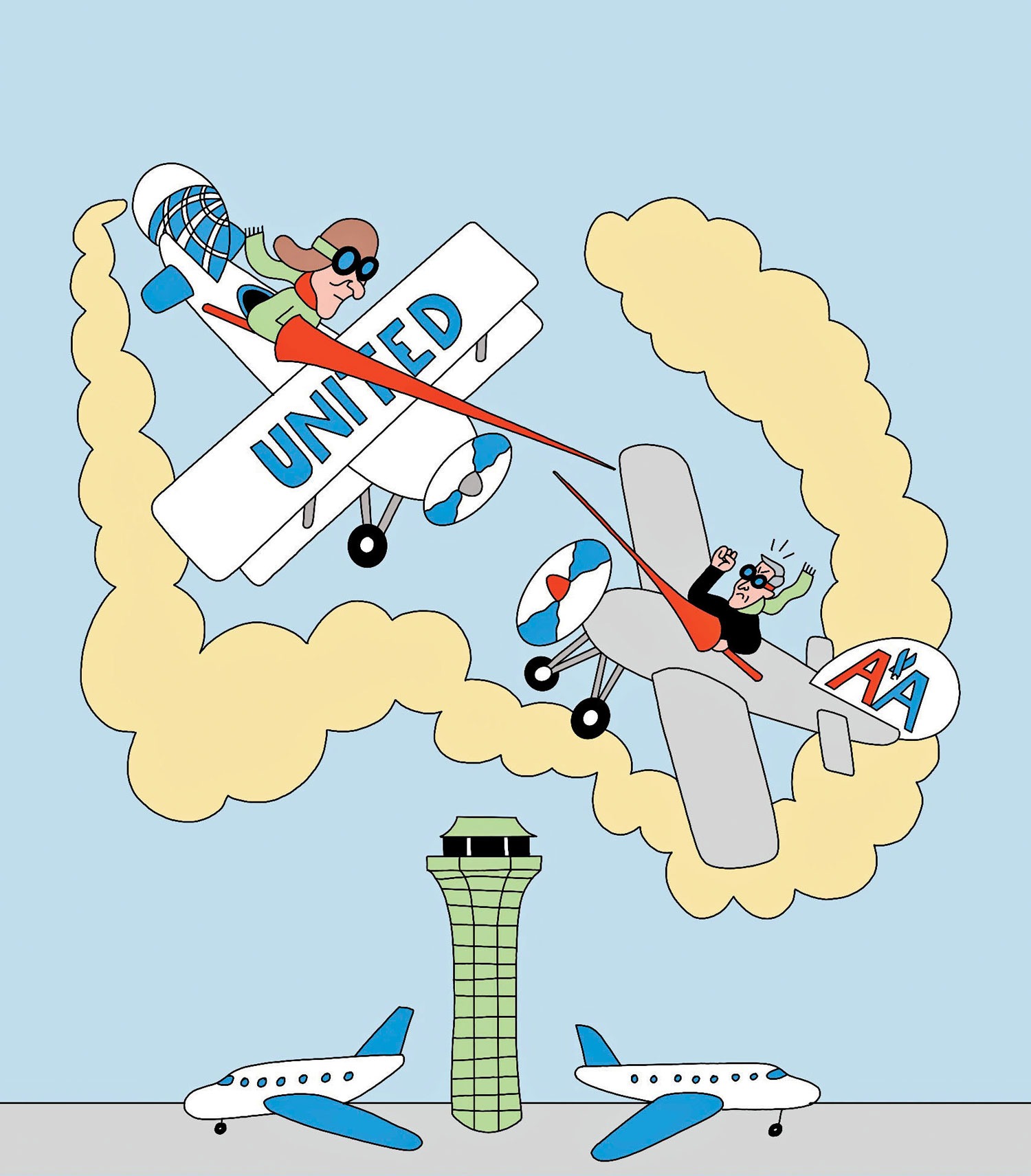

It’s fitting that O’Hare International Airport owes its name to a World War II naval aviator, because it has become the center of another kind of battle, this one fought across boardrooms and tarmacs and pitting two airline giants: United and American. Stirring things up is United CEO Scott Kirby, who never misses an opportunity to dis American, his former employer, repeatedly scoffing at its attempts to boost its presence at O’Hare. American has punched back by announcing it will add routes from there. Then, in late January, United peppered the city with billboards boasting of its route and performance superiority at the airport and trolling its rival with the tag “AAdvantage, United.”

It’s all part of the airlines’ ongoing fight for market share and access at O’Hare, where the Chicago-based United has the hometown advantage and more gates. It intends to squeeze out its rival, but American, headquartered in Fort Worth, Texas, is just as determined to maintain the airport’s status as a dual hub. After all, O’Hare’s central U.S. location makes it a premier spot for domestic and international connections. “It is one of the few airports in the world that genuinely is able to be home to major airline alliances,” says John Grant, chief analyst at the travel data company OAG.

Industry analyst Robert Mann Jr. characterizes the conflict as a battle of press releases and big egos: “Mr. Kirby is attempting to essentially extend United’s lead in Chicago, and this put up a marker for [American CEO] Mr. [Robert] Isom, who has decided that he would like to even the score.”

The professional history between Kirby and Isom may color the acrimonious relationship. In 2016, American pushed Kirby out as president, sending him packing with a $13 million severance package, and promoted then-COO Isom. Kirby quickly landed at United, where he started as president, then ascended to CEO in 2020.

Things began to heat up last May when the City of Chicago reallocated gates at O’Hare based on flight activity. American lost four, dropping its count to 59, while United picked up five, giving it 95. That set off a lawsuit from American, which alleged that the city had breached its lease agreement by taking gates away prematurely, before the airline had a chance to rebuild its traffic postpandemic, and hampered its plan to grow there. But in September, a Cook County judge rejected American’s request for an injunction.

“Competition is good. It’s good for the airport, it’s good for the traveling public. It leads to more routes. It leads to more competitive fares.”

— Michael McMurray, commissioner of the Chicago Department of Aviation

Then, in November, Kirby appeared on the podcast Airlines Confidential. When asked how he thought the domestic market would shape up over the next five to 10 years, he said he expected to see only “two large, revenue-diverse, full-service, brand-loyal airlines,” meaning United and Delta. “Everyone else is sort of competing for spill traffic.” As if that weren’t enough of a dig at his rival, he added that he “would not want to play [American’s] hand” at O’Hare.

But Kirby wasn’t done. A couple of months later, during an earnings call, he told investors that his airline had drawn “a line in the sand” at O’Hare in the turf battle, declaring United’s intention to assert its dominance there: “We’re not going to allow [American] to win a single gate at our expense. We’re going to add as many flights as required to make sure we keep our gate count the same in Chicago.”

American did not take kindly to getting strong-armed by Kirby. The next day, the airline announced it was adding three routes out of O’Hare this year: to Allentown, Pennsylvania; Columbia, South Carolina; and Kahului, Hawaii.

“While it’s clear that one hub carrier would prefer less competition at O’Hare, the inconsistent, third-party claims regarding our performance are unsubstantiated,” American said in a statement. It reasserted its commitment to O’Hare, pointing out that “over the course of nearly a century” it had “invested billions of dollars” in its operations there. The airline intends to boost its share of O’Hare flights to 39 percent by summer. But it will have an uphill climb catching up to United, whose share will be close to 49 percent, Grant says.

The push by both carriers for more flights out of O’Hare has sparked new discussion over the airport’s long-delayed expansion — specifically, whether the construction schedule should be revised. As of now, the plan is to continue work on a satellite concourse, which will add 19 gates, followed by the new international terminal and, finally, a second satellite concourse. But with capacity already tight at the nation’s busiest airport (traffic has recovered from its pandemic lows), there is concern that closing Terminal 2 to make way for the international terminal construction could exacerbate the squeeze.

“We risk entering a period where there’s fewer gates available,” says DePaul University professor Joseph Schwieterman, who published a paper in December on O’Hare’s coming traffic issues. “That could be a messy, stressful period, unless the sequencing of terminal construction has changed.” In November, the city disclosed that it was in talks with airlines to potentially do just that. As the airport’s top carriers, United and American will have a major say.

Chicago Department of Aviation Commissioner Michael McMurray anticipates that a decision will be reached in the first quarter of this year. “But as we go through this project, it could very easily change,” he says, adding that the amended schedule could include some hybrid phasing.

O’Hare could try to follow New York’s LaGuardia Airport, which kept its gates open during its recent massive renovation. “They built these long piers and built a sky bridge to get over these things and keep the gates open,” Schwieterman says. “But that was largely done during the pandemic. They didn’t have people racing between flights. It would be hard to imagine doing that at O’Hare when you have all these tight windows.”

With United and American locked in a corporate blood feud, do O’Hare and, by extension, Chicagoans stand to benefit? McMurray thinks so: “Competition is good. It’s good for the airport, it’s good for the traveling public. It leads to more routes. It leads to more competitive fares. It leads to more direct routes for the traveling public. So right now, it’s a good thing — we’re not getting in between that competition.”