Bill Daley is a scion of Chicago’s Democratic royalty. His father ran the city for 21 years, and his brother for 22 years, both oiling the party machine. He has served two Democratic presidents: as commerce secretary under Bill Clinton and White House chief of staff under Barack Obama. And yet he’s pushing for a measure that would effectively reduce his party’s stranglehold on the state.

Why? When he looks at the Illinois legislature, he sees a statehouse that doesn’t truly represent the people. In the last election, Democrats won 66 percent of seats in the General Assembly despite claiming only 55 percent of the votes. This, Daley believes, is bad for democracy.

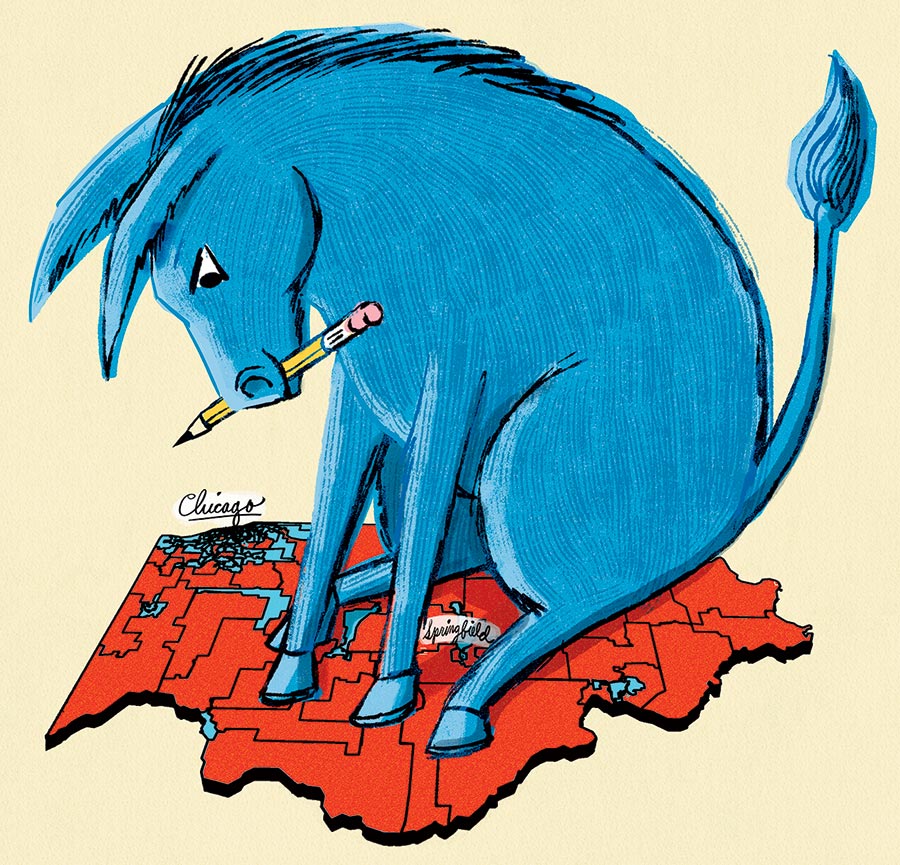

The culprits are Illinois legislative maps advantageously drawn by Democrats. (The state Senate one received an F from the watchdog Princeton Gerrymandering Project.) To address that, Daley has signed on as cochair of Fair Maps Illinois, a bipartisan group aiming to establish an independent commission to draw the maps, taking redistricting out of the hands of the state legislature’s majority. He’s leading the effort with former Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, a Peoria Republican.

“Whether it was the Republicans in the ’90s or the Democrats now, you end up with a system where the primary is everything.”

— Bill Daley, cochair of Fair Maps Illinois

“There’s no doubt that just about every state where the legislature draws the maps, the majority, especially when you have a supermajority, are out to protect their seats,” says Daley. Not only does that lead to a state legislature that doesn’t proportionally represent the populace, it also creates districts so safely in control of one party that the general election is rendered moot. Last November, almost half the races for House seats — a staggering 54 of 118 — went uncontested, meaning the other party didn’t even bother running a candidate because there was no realistic chance of winning.

“Whether it was the Republicans in the ’90s or the Democrats now, you then end up with a system where the primary is everything,” says Daley. The problem with that is it tends to favor political extremism over moderation, since candidates don’t have much incentive to court voters of other persuasions. “People just run to the right or run to the left.”

The Fair Maps proposal would put a binding referendum on next November’s ballot to establish the map-drawing commission. Composed of four legislators and eight nonlegislators, all appointed by legislative leaders, the commission would be tasked with drawing maps that respect municipal, county, and township boundaries; it would also be prohibited from using partisan information or voting records, which are the secret sauce to gerrymandering. The new maps would not take effect until the 2032 elections.

This isn’t the first push get such a referendum on the ballot. In 2016, one group collected enough signatures, but its proposal was struck down by the Illinois Supreme Court. It ruled that a citizen initiative can address only “structural and procedural” issues; that one would have overstepped by giving the state auditor general the power to select commission members. This time, says Michael Dorf, general counsel for Fair Maps Illinois, the proposal has been crafted to avoid such constitutional issues by involving legislators in the process and giving the commission the power to handle only state-level seats.

If the referendum gets on the ballot (its supporters plan to collect 600,000 signatures — nearly double the number required — to withstand challenges), it will almost certainly pass. In the past, whenever voters in Illinois have been asked about establishing independent redistricting commissions, 70 to 80 percent of them have approved the nonbinding referendums.

Although Republicans are taking heat on the national level for torturing district lines to their benefit, namely in Texas and Missouri, the reality is that Illinois Democrats have been doing the same thing for years. Complaints about gerrymandering here go all the way back to the 1858 race between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas for a U.S. Senate seat. Lincoln’s Republicans won more votes for the state legislature, but the Democrats won more seats, guaranteeing Douglas’s reelection in the days when legislatures chose senators. “An apportionment law ridiculously adopted to the existing facts has given Mr. Douglas a substantial but undeserved triumph,” groused the Republican Chicago Tribune. “Now who’s cheating?”

Today, 167 years later, Illinois Republicans are still complaining about Democratic gerrymandering: a congressional map under which they won only three out of 17 seats (despite that fact that President Donald Trump received 43.5 percent of the state’s votes), and an Illinois General Assembly map that has consigned them to superminorities in both chambers. “Democrats’ God is power and control, and their church is the government,” says the chair of the Illinois Republican Party, Kathy Salvi. “They have used that power to draw maps that disserve the people of Illinois.”

But as old as gerrymandering is, the practice became a dark art under former House Speaker Michael Madigan, who used computer technology that incorporated detailed voter data, allowing him to draw maps that eventually gave the Democrats a veto-proof majority by packing Republicans together in selected districts. The tradition has continued under his successor, Emanuel “Chris” Welch, who in 2021 passed the map that has led to the party’s current massive majorities in Springfield.

The Fair Maps Illinois proposal does have its critics, and they’re not just Democrats who are reluctant to give up power. CHANGE Illinois, a nonpartisan government watchdog group, has long advocated for independent redistricting, but it’s skeptical of this initiative because it will include politicians in the process. “I worry that there’s an overreaction to past court decisions, and we could end up with a proposal that does more harm than good,” says the group’s executive director, Ryan Tolley. With politicians both serving on and appointing other members to the commission, the initiative squanders a chance at real independence and reform, he argues.

Republicans, unsurprisingly, have embraced Fair Maps Illinois: They think the proposal will allow them to win more seats and claw their way out of the superminority. But Salvi argues it would be good for the state as a whole by promoting accurate representation as well as encouraging turnout among voters who (not unjustifiably) “think it’s a rigged game.”

A “fair” map doesn’t mean a 50-50 split. Given the partisan tilt of Illinois, it’s unlikely that independent redistricting would return the Republicans to the power they enjoyed in the late 20th century anytime soon. But it could at least give their constituents more of a say and, Daley points out, disincentivize the state GOP from continuing to push extreme candidates. That’s how democracy is supposed to work: Voters choose their politicians, not the other way around.