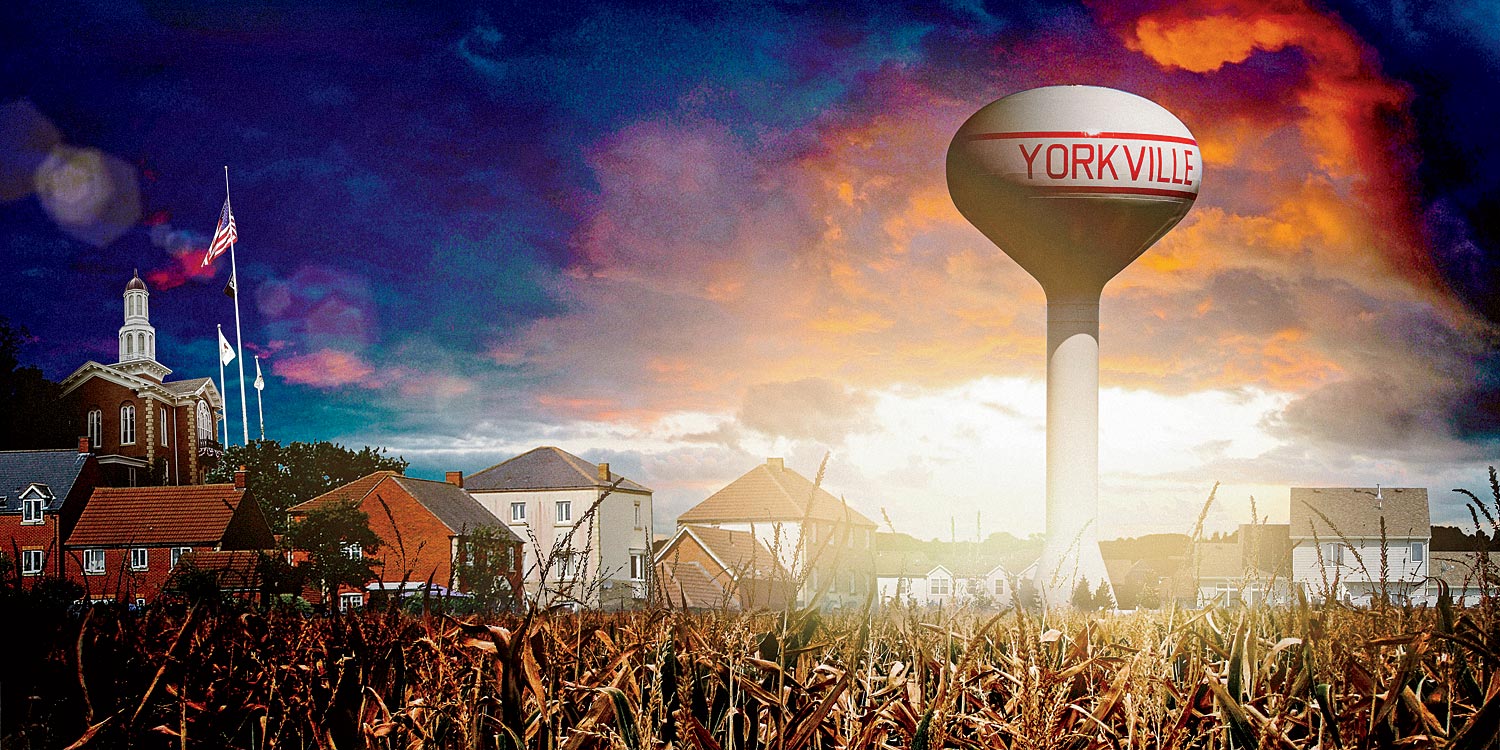

The TV news trucks that had clogged traffic along the block-long business strip on Bridge Street were gone. So were the swarms of strangers knocking on the doors of seemingly every baby boomer to have graduated from Yorkville High School, asking questions outside the Silver Dollars Restaurant, poring through yellowed yearbooks at the Yorkville Public Library. No more photographers were snapping shots of the high school, an unremarkable red-brick building past which looms a bulbous water tower. On a sunny morning in early July, tiny Yorkville, Illinois, was quiet.

After driving southwest for an hour and a half, beyond the urban sprawl of Chicago and the even-sprawlier western suburbs, through rolling farm country hard by the Fox River, I pulled up at Yorkville’s historic Kendall County Courthouse. This hilltop Italianate structure serves as the de facto town square, the site of community meetings, reunions, and weddings.

It’s also central to the story of Dennis Hastert, the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1999 to 2007.

Advertisement

The courthouse is where Hastert—who grew up in Oswego, a few miles down the road, but for most of his life has called Yorkville home—took his first driver’s test as a nervous 16-year-old. It served as the backdrop for a 1976 parade that the town threw for him and his triumphant Yorkville High wrestlers after the team, which Hastert coached, won the state championship. It was here, too, on the courthouse’s front steps, where Hastert launched his political career, announcing a run for the statehouse in 1980 and, six years later, a campaign for Congress.

By then, the courthouse, which dates to the Civil War, was falling into disrepair. Kendall County was outgrowing it anyway. So in the early ’90s, county officials decided to build a new facility two miles away. They tried to get someone to take the white elephant off their hands, but it needed so much work that no one wanted the place, not even for a dollar. Local preservationists failed to raise enough money to save the building. With no takers, the old courthouse was doomed.

On the day in June 1998 when the county board met to seal the building’s fate, Hastert swooped into the crowded boardroom, a superhero in oversize eyeglasses and a rumpled suit jacket. He asked the group to postpone its vote. And not in vain. Hastert brought home a $1.5 million grant from the National Park Service to save and restore the courthouse. State lawmakers chipped in a million more, and the building was spared from the wrecking ball.

By the time Yorkville rededicated the restored courthouse at a special Fourth of July ceremony in 2002, Hastert was the most powerful man in Congress, just two heartbeats from the White House. Around these parts, he was even more: a living, breathing monument, as much a treasure as the historic structure he had helped save.

Opening the heavy courthouse door and walking into the main corridor, I immediately noticed a bronze plaque prominently affixed to the wall. A relief image of Hastert looked back at me. Yorkville High School Wrestling Coach, State Representative for Kendall County, United States Congress, Longest Serving Republican Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. At the plaque’s 2012 unveiling ceremony, Hastert remarked, with typical modesty, “I never really thought they’d be hanging my puss off the wall.”

Nor, I would bet, did he ever imagine that three years later he would be asked to come to a different courthouse 50 miles away—the Everett McKinley Dirksen United States Courthouse in downtown Chicago—for a more ignominious event: his arraignment.

On May 28, Yorkville and the rest of the world would learn that Hastert, 73, had been indicted on charges of breaking federal banking rules regarding large cash withdrawals and lying to federal agents in order to conceal some unspecified “prior misconduct.” Prosecutors claim that since 2010 Hastert had been paying off someone, identified in court documents only as Individual A, to the tune of $3.5 million to keep quiet about this alleged misconduct.

The next day, various media outlets, citing law enforcement sources, reported that the unnamed recipient of Hastert’s alleged hush money was a former Yorkville High student who claimed that Hastert had sexually molested him decades earlier. A few days later, a Montana woman came forward, accusing Hastert of a years-long sexual relationship with her older brother in the late 1960s and early ’70s, when the boy was the student equipment manager for Yorkville’s wrestling team. (That man, Stephen Reinboldt, can’t be Individual A: Reinboldt died of AIDS in 1995, 15 years before Hastert began his alleged payments.)

Beyond the initial shock and awe (“Hometown Rocked by Scandal,” “Shadow over All-American Town”), virtually nothing was written about Yorkville, where the alleged abuse took place. As the days went by, unanswered questions nagged at me. If Hastert had indeed sexually abused Reinboldt and Individual A when he was a high school coach and teacher, I wondered, could there be more victims? And in a tiny place where everybody knew everybody’s business, how could such behavior have stayed secret for so long?

I had come to Yorkville to find out.

A few days later I headed to Yorkville’s library and asked a librarian where I could find the local history and genealogy room. She grimaced. “You’re here about Denny?” she asked, using the nickname that locals invariably use when referring to Hastert. “You’re a little late,” she added. “The other reporters were here weeks ago.”

Paging through various documents, including an oral history of the town written by another librarian, I realized that the Yorkville of 1965—the year after Hastert graduated from Wheaton College, an evangelical Christian school, and started teaching history and social studies at Yorkville High—was dramatically different from what residents call “new Yorkville,” population 17,000. Instead of the hundreds of developer-built tract houses I’d driven past, there were hundreds of acres of cornfields. The chain restaurants and big-box retailers that cluster the intersection of Route 47 and Veterans Parkway did not exist. No children splashed at Raging Waves, a 45-acre Australian Outback–themed water park.

Back then Yorkville was a speck of a town, with just 1,500 residents, mostly farmers. Many of the boys Hastert taught or coached grew up the same way he had: working class, with God-fearing parents who passed down their unflagging work ethic, small-town pride, and conservative values. (Hastert’s father, Jack, was a funeral parlor embalmer turned feed store owner turned restaurateur; his mother, Naomi, worked at a grocery store.)

I started sorting through the Yorkville High yearbooks for the 15 years of Hastert’s tenure as a teacher (classes of 1966 through 1981). Photos of a broad-shouldered, fit-looking, handsomely coiffed young man gave way to a shaggy-haired, rather disheveled guy with a belly that sags over his pants. Before that transformation began, during Hastert’s second year at Yorkville, Stephen Reinboldt entered the school as a freshman.

If I hadn’t known to look for him, I probably wouldn’t have noticed the scrawny, baby-faced kid among the strapping wrestlers in their unitards. Reinboldt is even easier to miss in the picture of the football team, for which he was also the equipment manager. (Hastert coached the football team too.) I flipped through pictures of Reinboldt before he graduated in 1971: student council, letterman’s club, French club, glee club, pep club. In most of the photos, he’s smiling from ear to ear.

What about Individual A? In the indictment, prosecutors said only that this person “has been a resident of Yorkville” who “has known . . . Hastert most of Individual A’s life.” While the indictment does not give Individual A’s age, people in Yorkville speculate that he must have been on or affiliated with the wrestling team during Hastert’s years as coach. I counted up the boys pictured in the yearbooks. Yorkville High had only about 400 students each year back then, about 200 of them boys. The wrestling team typically had 10 to 20 members.

When I finished going through the yearbooks, the librarian asked me if I had found what I was looking for. I interpreted this as her polite way of saying, “See? I told you. If you’re searching for Individual A, you came to the wrong place. You won’t find him by looking at yearbook pictures.”

I explained that I hadn’t come to crack the mystery of Individual A per se. Don’t get me wrong, I told her: I wanted to know who that person was as much as the next reporter. (So, on that note . . . did she know anything? No.) But mostly, I said, I wanted to get a clearer picture of what Yorkville High was like back when Hastert coached and taught there—get a better feel for the place and the people to help me understand how and why Hastert’s behavior, if true, stayed quiet for so long.

To which she responded, “Weeeell, this is the best-kept secret this town ever had! And there aren’t many secrets here.”

To illustrate, she told me about one afternoon when her son was walking home from school. Someone driving by noticed that he had a big wad of chewing tobacco tucked in his lower lip and that he was spitting out the juice. “I heard the whole story,” she said, “before my son even walked through the front door.”

She paused. In the days when Hastert was teaching here, she reminded me, “the town was even smaller.”

On one thing everyone can agree: Dennis Hastert was obsessed with wrestling. Even in class, “wrestling was all he ever talked about,” said Jeff Nix, 63, a former Yorkville High wrestler who graduated in 1970. (He currently owns a shop in nearby Plano that digitizes old videotapes.) “When we took history with him, we talked about wrestling. When we took government, we talked about wrestling.”

Advertisement

The coach set out to build not just a winning program but a dominating dynasty, Nix told me. He devoted innumerable hours to his young charges: before class, after class, in the gym. He scheduled tougher competition against bigger schools. He got his student wrestlers terry-cloth robes so they could feel like prizefighters. He took vanloads of boys to wrestling camp in Virginia, where they learned the famous Granby roll, an advanced escape move that was virtually unknown here at the time.

Hastert’s involvement with young people went beyond sports and academics. He also volunteered at the International YMCA and led an Explorer Scout group, chaperoning male students to the Grand Canyon and on diving trips in the Bahamas. And he liked to take kids for rides in his Porsche 911. “Denny was a bachelor at the time,” recalled Nix. (Hastert married Jean Kahl, a Yorkville gym teacher, in 1973, when he was 31.) “And he got a brand-new Porsche every year. A red one, a black one, a blue one. Back then, it was a pretty hot car. All of us liked cars. We thought that was cool.”

Each year, the Yorkville Foxes got better. As they did, the old gymnasium where the high school held its wrestling meets, known as the Pit, began to fill to capacity with, as the yearbook put it, “vivacious crowds.” That was no exaggeration, longtime Yorkville residents told me: The meets were town-wide events. “The days when Denny was here, it was the biggest thing,” said Frank Babich, who was Yorkville High’s principal from 1985 to 2003.

Hastert’s wrestling teams racked up a trophy case’s worth of medals and titles: 14 conference, six regional, and four sectional championships; second- and third-place finishes in 1974, 1977, 1978, and 1979; and, of course, the top prize in 1976. Forty-eight of Hastert’s wrestlers qualified for the state tournament, more than half of them placed, and eight won individual championships. In 2003, Hastert was inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame.

Echoing the dozen or so former Hastert wrestlers who have spoken to reporters, Nix said that he was dumbfounded by the accusations against his old coach. “If it’s true, I don’t have a clue why no one knew,” Nix said. “Back then, if you got a crewcut at the barbershop, everybody knew you got a crewcut before you got to school. There were no secrets anywhere. Maybe we just all had our blinders on. Maybe we had the wool over our eyes.”

From everything I’d heard about the legendary political kingmaker of Kendall County, I figured he would choose a power spot to meet for lunch, some dark-paneled, white-tablecloth restaurant that served thick steaks, where we’d sit in his regular booth and get sucked up to by the old-timey maître d’. But Dallas Ingemunson wanted Buffalo wings. So we met at Wings Etc., a franchise restaurant with loud music and flat-screens galore in a nondescript strip mall a couple of doors down from a Dollar General.

At 77, Ingemunson—who was sporting a navy polo shirt, shorts, and Birkenstocks—is out of the political game. Though you wouldn’t know it. During our lunch, well-wishers interrupted us twice; passersby waved. He seemed to know everyone. No wonder, given that Ingemunson served as Kendall County state’s attorney for 26 years (from 1970 to 1996) and as the Republican county chairman for 34 years (1973 to 2007), the quintessential big fish in a small pond. For more than three decades, he made or broke local political careers—most famously, Hastert’s.

Over those wings, Ingemunson recalled the first time he met Hastert: “He came to me in my state’s attorney’s office one day and said, ‘I’m gonna run for the statehouse, and as a matter of courtesy, I’m telling you.’ ” Ingemunson giggled in a high-pitched titter that belied his age. “He wasn’t asking.”

Hastert lost that race, a primary campaign in 1980. But Ingemunson came away impressed by his work ethic, his moxie, and his seemingly genuine desire to help people. “Some people want to get into the political business and I question why they’re doing it. I never questioned Denny’s reasons. Whether it be in sports or politics, or whatever else, he’s always wanted to help people.”

Ingemunson described how Hastert was able to rise from wrestling coach to the heights of power in Washington. Thanks to Ingemunson’s maneuvering, when an incumbent died unexpectedly not long before the 1981 election, Republican Party leaders put Hastert on the ticket for the Illinois House. Several years later, after another congressional incumbent had to withdraw because of poor health, Ingemunson again helped slate Hastert. Both times the candidate ran in considerably shortened campaigns, avoiding public primary contests altogether. In doing so, he circumvented much of the intense scrutiny that candidates typically face.

Hastert’s eventual ascension to the speakership was practically accidental. His fellow Republicans hastily drafted him into the role during a media frenzy that focused on the extramarital misdeeds of his two predecessors, Newt Gingrich and Bob Livingston. (Hastert was viewed as the safe, no-skeletons-in-the-closet choice.) In Hastert’s 2004 memoir, his longtime chief of staff half jokingly summed up his boss’s charmed path to the speaker’s chair: “Illness, illness, scandal, and dumb luck.”

But his rise wasn’t all happenstance. Hastert also appeared to have in spades two qualities that the best politicians possess: relatability and trustworthiness. It’s nearly impossible to find a profile of or anecdote about the man in which he isn’t hailed as a “straight shooter” or a “regular guy.” Plain of appearance (“He looks like an unmade bed,” a Democratic pol once described him) and of speech (“He speaks in a sticky downstate-Illinois monotone,” the author Jonathan Franzen observed in a 2003 New Yorker profile), Denny epitomized the ordinariness of his hometown. As a Yorkville resident told the Sun-Times the day after Hastert was named speaker in 1998: “He was the kind of guy you see at Pizza Hut.”

Once in office, Hastert kept a low profile. Friends say that he never sought out the political limelight, which he was by nature ill suited for anyway. Neither did his wife. Jean shunned the campaign trail and the political social circuit, staying in Yorkville (Hastert shared an apartment in D.C. with Scott Palmer, his chief of staff) and keeping her gym teacher job as she raised their two sons. (Josh, 40, works as a lobbyist in D.C., and Ethan, 37, is a lawyer and a partner at Mayer Brown in Chicago.) “I think people respected that Denny never got caught up in the celebrity Washington power structure,” said Ray LaHood, the former Illinois congressman and U.S. secretary of transportation and a longtime friend of Hastert’s. “He never forgot where he came from.”

It endeared Hastert to the town that even as he became a figure in American history books, famous around the world, he never acted like he was bigger than Yorkville. “Not a lot of people have come out of here and been successful and stayed,” another local Republican insider told me. “To say he was the patron saint of the town is no exaggeration at all.”

Hastert’s knack for getting along with people—he had lots of political allies—also kept him from being a target of those looking to dredge up personal dirt. After that one close first race for Congress, he cruised to reelection every two years, facing little to no scrutiny and typically winning 2 to 1, sometimes 3 to 1, over the Democratic sacrificial lambs.

Advertisement

Another reason constituents loved Hastert: He consistently handed out more pork than a swine barn holds at a county fair. He funneled hundreds of millions of federal dollars toward transit and infrastructure projects in Kendall County and the rest of his district, for example, including the ultimately scrapped Prairie Parkway, which would have connected Interstates 80 and 88 and for which Hastert earmarked $207 million. Once he even slipped $250,000 for the Yorkville candy company Amurol Confections, a subsidiary of the chewing gum giant Wrigley (now part of Mars), into the federal defense budget. (The funds were to study a caffeinated gum; Hastert claimed the project would create 400 jobs.) Due in part to such largess, Kendall was the fastest-growing county in the nation—you read that right—from 2000 to 2010, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Hastert managed to shrug off controversies that could have torpedoed other politicians’ careers, from the House check-cashing scandal in 1992 to various dustups involving his mentor in the House, Texas firebrand Tom DeLay. Consider the 2006 revelation by a nonpartisan D.C. watchdog group, the Sunlight Foundation, that Hastert, Ingemunson, and their old Yorkville friend Thomas Klatt had amassed 130-plus acres of farmland near the proposed route of the Prairie Parkway. The trio quickly flipped the land, and Hastert raked in a cool $2 million profit. Critics assailed the “Hastert Highway” deal, likening it to insider trading. (“Highway Robbery,” Salon harrumphed.) But the scandal barely registered on Yorkville’s public outrage meter. If it wasn’t illegal, why couldn’t Denny make a buck like anyone else? Besides, for everything he’d done for the town and the rest of the district—heck, for the whole country—over the years, he deserved it and then some.

A few months later came Pagegate. As you’ll recall, in September 2006, Republican representative Mark Foley of Florida abruptly resigned after it was revealed that he was sending sexually suggestive emails and instant messages to young male congressional pages. It soon came out, in the press and after a House ethics committee investigation, that at least two of Hastert’s colleagues, including John Boehner, had warned the speaker about Foley’s graphic emails months earlier. Hastert failed to intervene, and Foley’s reckless behavior continued.

After his 2007 retirement, Hastert told the Daily Herald that he and other Republican leaders “did what we could with what we knew.” The ethics committee found “a disconcerting unwillingness to take responsibility for resolving issues regarding Representative Foley’s conduct.” Nevertheless, Yorkville once again gave its hometown hero a pass.

As we were finishing up our lunch, I asked Ingemunson if he or anyone else had ever conducted on Hastert the painstaking vetting that campaigns almost always do in order to avoid potentially embarrassing disclosures later.

“No, I never had any reason to,” he snapped. “I knew him well enough.”

“Did you know about any sexual misconduct allegations?”

“No! Nobody knew!” he said, glaring at me.

“No whispers or rumors?” I prodded.

“I never heard ’em. Nobody ever heard anything!”

After a few more excruciating minutes in which Ingemunson barely replied to my questions or made eye contact, our interview was over.

Robyn Sutcliffe has lived in Yorkville for 21 years. One afternoon, I stopped at her ice-cream shop, Foxy’s, a cheerful pastel-painted shack right on the banks of the Fox River, in the heart of downtown. I asked her why so few people around Yorkville seemed to believe the allegations against Hastert. She plugged her ears and chanted, “La, la, la, la, la!

“People just don’t want to believe it,” she finally said. “People don’t want to think badly of someone they love and respect. And Denny’s just so well loved.”

Among some Yorkville residents, however, doubts were beginning to settle in, for two main reasons: the huge sum of money allegedly involved and Hastert’s silence.

In Yorkville—where the median single-family house sells for about $200,000—$3.5 million is practically Trump-like. Even some Hastert supporters can’t explain why on earth he would have agreed to pay somebody so much money. “Jeez, it’s staggering,” said his friend Klatt, 76. Wondered Nix, the former wrestler: “What was he paying somebody for? If it wasn’t for [those alleged payments], I wouldn’t believe any of [the sexual allegations].”

Advertisement

Then there were the lengths to which Hastert allegedly went to conceal the payments: accounts at four different banks in the area; 15 withdrawals of $50,000 each between June 2010 and April 2012, which bank officials began asking him about; then, prosecutors say, scores more withdrawals of increments below $10,000 each—an illegal practice called structuring. “I think it’s obvious the only reason to do that is to hide it from the wife and kids,” said a Republican insider who asked not to be named.

Other than the not-guilty plea entered by his lawyers, Hastert has said nothing publicly about the allegations in the indictment or—more troubling around here—about the sexual abuse accusations. Of course, defense lawyers generally think it’s a bad idea for their clients to say much, if anything. (Through his attorney, Thomas Green, Hastert declined my interview request.) But to a lot of folks here, legal rationales don’t mean squat. They see honesty as a more straightforward concept, straight from the lesson of George Washington and the cherry tree: If you did it, own up to it. If you didn’t, speak up. Defend yourself.

I asked Sutcliffe if she thought that people around town needed to hear Hastert directly address the accusations. Break his silence. Would that quell some of the doubts? “I think they would love to hear he didn’t do it—that this is all a mistake,” she said. “But . . .” Her voice trailed off.

Stephen Reinboldt finally broke his own silence eight years after graduating from Yorkville High, his younger sister, Jolene Burdge, told ABC News in June. He and Burdge were at a bowling alley, watching another brother compete in a tournament. Reinboldt confided to Burdge that he was gay, and she asked him when he’d had his first same-sex experience. “He looked at me,” Burdge told ABC News, “and said, ‘It was with Dennis Hastert.’ ”

Burdge did not respond to several interview requests for this story. But she has said that Hastert became like a father figure to her brother and that their own late father was an alcoholic. At the time, she saw Hastert as Stephen’s savior. “Here was the mentor, the man who was, you know, basically his friend and stepped into that parental role, who was the one abusing him,” she said on ABC News. “He damaged Steve, I think, more than any of us will ever know.”

Reinboldt died at age 42 in Los Angeles, where he had been trying to make a career in the entertainment industry. At his funeral viewing, Burdge told ABC, Hastert showed up. She said she followed the politician to the parking lot and confronted him. “I want to know why you did what you did to my brother,” she recalled saying. “And he just stood there and stared at me. Then I just continued to say, ‘I want you to know that your secret didn’t die here with my brother.’ And again, he just stood there and he did not say a word.”

For help with the question I was still racking my brain over—If the allegations are true, how could the secret have stayed hidden for so long?—I called Carla van Dam, a psychologist in Washington State and a noted expert in child sexual abuse. Instead of answering my question directly, she told me the story of Gary Little.

Little had coerced teenage boys into having sex with him in the 1970s when he was a young lawyer and a teacher at an exclusive prep school. Even as Little went on to become an assistant state’s attorney general and then chief counsel for the Seattle School District, his victims apparently said nothing.

Little was elected to the King County Superior Court in Seattle in 1980. By 1981, a judicial commission had reprimanded the judge—privately—for taking children to his home. Little continued seeing youths outside the courthouse, but that same commission did nothing. In 1985, he was transferred to nonjuvenile cases.

One day in August 1988, Little learned that the Seattle Post-Intelligencer would be publishing a story about his secret life the next morning. A few hours later, he shot himself in the head in the hallway outside his chambers.

After Little’s suicide, it became clear just how many people had known his secret. Lawyers who handled juvenile cases were aware of the judge’s sexual predilection for blond, blue-eyed boys. When they had clients who fit that description, they would try to get their cases assigned to him in the hopes of a more favorable ruling. Many in the media, too, had found out about Little’s behavior by the mid-’80s but didn’t go public. One TV reporter even confessed that he had walked in on Little kissing a male student two decades earlier. “Everybody knew,” said van Dam, “but nobody knew.”

Though she stressed that she wasn’t privy to any details of the Hastert case beyond those in news reports, van Dam said that she has studied enough cases over the years to be dubious of the public narrative that has emerged so far. “People know. Especially in small towns, people know who the drunk is on the block. People know. They choose to do nothing because it’s too hard.”

According to Sarah K. Cowan, a sociology professor at New York University who studies secrecy, several forces could have been at work here. Sometimes well-meaning people keep quiet in the belief that they are protecting victims from damaging attention—especially common in sexual abuse cases. Add a powerful figure into the mix and their hesitation to speak grows, Cowan told me. The likelihood of secrets spreading about people in positions of authority often depends on whether those secrets are likely to be believed. “To accuse a beloved community leader of something salacious and illegal and then not to be believed?” Cowan said. “The accuser would be an outcast.”

I immediately thought of what Burdge recalled her brother saying when she asked him why he hadn’t told anyone about Hastert: In this town, who is ever going to believe me?

Advertisement

By my count, at least five people had experienced or heard about Hastert’s alleged behavior: Individual A; Stephen Reinboldt; Jolene Burdge; an unnamed friend of Reinboldt’s, who said on NBC News that Reinboldt confided the sexual relationship back in 1974; and Mel Watt, a Democratic congressman from North Carolina. (Early in Hastert’s speakership, Watt had learned of allegations that Hastert had molested a former male student, The Huffington Post first reported in June. In a statement, Watt acknowledged that he had been told “an unseemly rumor”—he didn’t say who told him—but said he “took no action” because he had “no direct knowledge of any abuse.”)

Add in the person who told Watt. Plus the unnamed person with whom the FBI confirmed Individual A’s accusations, according to the indictment. Plus, as reported by a hyperlocal Montana news site called Last Best News, Burdge’s husband, her sister Carol, and a few other people who also knew. And perhaps include the person who, after Hastert’s indictment, commented on Burdge’s Facebook page: “I immediately thought of you when I saw this!!! You must be doing a happy dance!”

The only person who can really answer my questions, of course, is Dennis Hastert himself. He used to be a common sight around the Yorkville area: strolling the aisles of the grocery store, chitchatting at the post office. But in my half-dozen visits, I hadn’t seen him once. He appears to have largely gone into hiding, holing up at his Plano home, a green farmhouse set back from the road at the end of a long, gravel driveway, the property surrounded by a chain-link fence, or at his 400-acre spread near Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, some four hours away. “He doesn’t even come into town anymore,” Nix, the former wrestler, told me. “He disappeared.”

Sutcliffe, the owner of the ice-cream store, said sympathetically, “I’d be hiding out, too. He can’t show his face anywhere.”

Hastert’s friends worry about his health. At his June 9 arraignment—the last time he was photographed—the retired pol, who has diabetes, appeared much thinner than usual, his suit baggy, his tie a bit askew. (The next hearing in the case is set for October 20.) Even Klatt, one of his closest friends, said he didn’t recognize him. “All hunched over, straggly hair—I thought, What the hell?”

Passing through Yorkville on my drive back to Chicago, I thought about what Cowan had said when I asked her what impact Hastert’s disgrace might have on the town’s collective psyche.

“I don’t know what it does to a town,” she confessed after a long pause. “In my interviews in which people talk about others that they’ve held in high esteem and then were told that they did something terrible, the worst thing that happens is that they start to mistrust their own judgment. They become suspicious of others.”

Think of it, in other words, as if Yorkville, the community, experienced a certain cumulative loss of innocence. So what happens now when the next well-meaning teacher or coach comes around and takes special interest in his students, or wants to mentor kids or take them on field trips? Someone who, in the eyes of folks in Yorkville, behaves a lot like how Dennis Hastert did. Will he be seen as a good guy or a potential predator?