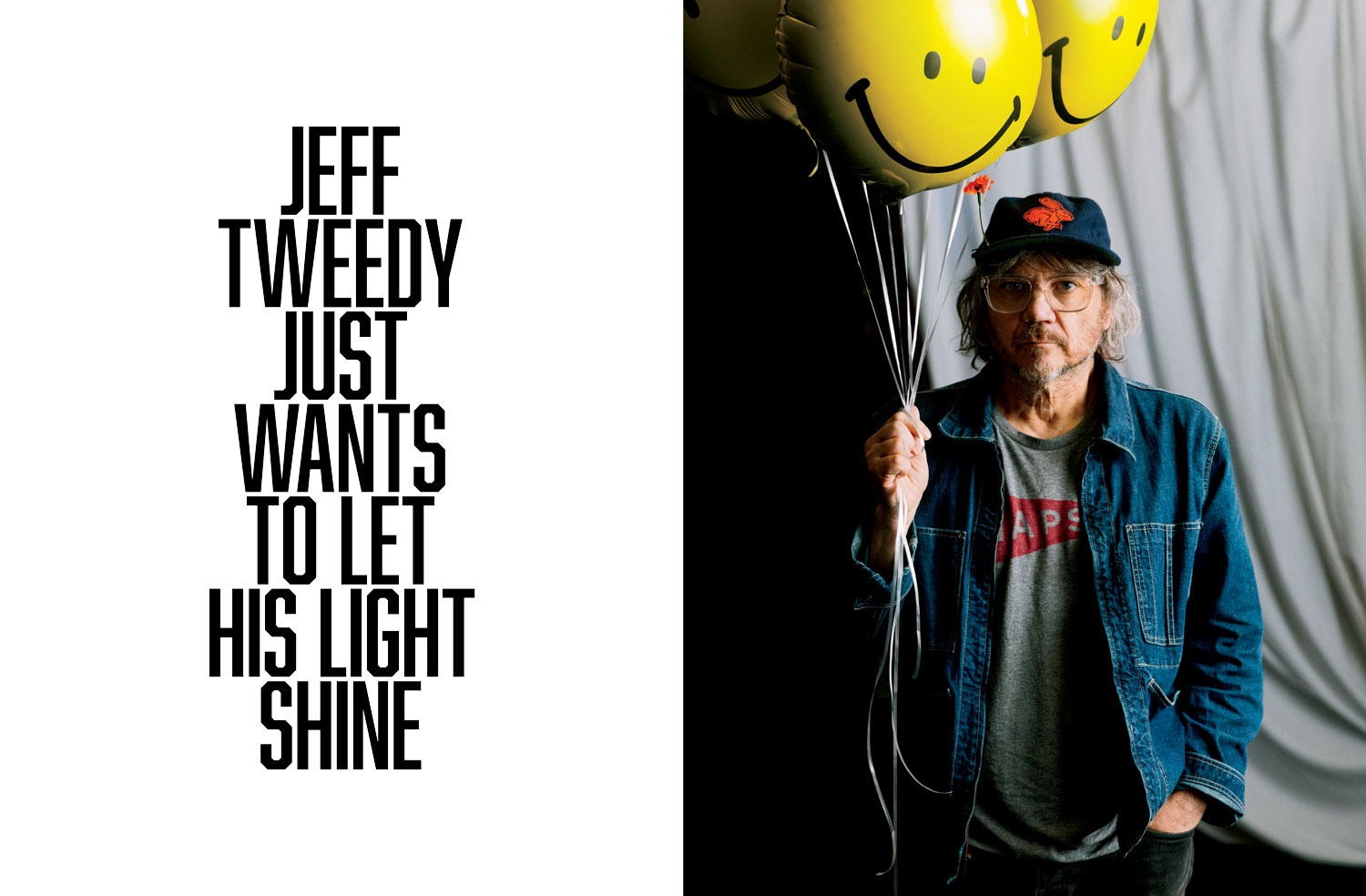

Here sits Jeffrey Scot Tweedy, alt-rock bard and best-selling author. Bearded, bespectacled, and behatted in a dark blue Texas Playboys ball cap with a burnt-orange rabbit logo and a tiny pink artificial flower clipped to its brim, the Grammy-winning Wilco frontman and longtime Chicagoan bellies up to a glass table in the modest but homey kitchen of the band’s Irving Park studio. The 5,000-square-foot, low-ceilinged space just off Irving Park Road, known far and wide as the Loft, has served as a recording space, a practice room, a place to store equipment, and a hangout pad since 1997. As such, it’s stuffed with all manner of musical implements and instruments, from amps and pedals to drums, keyboards, and guitars — especially guitars, scores of them, some upright and naked on stands, others protected in cases on metal shelves.

Tweedy is intimately, encyclopedically knowledgeable about these tools of his trade, knows each one’s sound and feel and which are best suited for which songs, including the 30 that pack his new triple album, Twilight Override. It is the 58-year-old Belleville, Illinois, native’s most ambitious solo studio project to date, a sonically diverse collection of gloom-busting tracks for our times — “sounds and voices and guitars and words that are an effort to let go of some of the heaviness and up the wattage of my own light,” he writes in the liner notes. “My effort to engulf this encroaching nighttime (nightmare) of the soul.”

Fresh from a rehearsal with his 20-something musical sons, Spencer and Sammy, and local musician and songwriter Liam Kazar for a show at the Newport Folk Festival, and before that a promotional photo shoot, Tweedy is tired and feeling a bit wonky in the head at the moment. While the migraines he’s long suffered from have abated of late, he’s well attuned to signs that his body needs recharging. For now, though, he’s still game for talking. And so he does, about everything from his long marriage and his latest album to the downside of ego and his determination to fight for democracy. “What I have control over,” he says, “is keeping my mind free.”

Here, voiced during a period in his life when the artist is even more introspective than usual, are Tweedy’s truths, in his own words.

All of my music is against the dark in a way. It’s like we’re on a road to ruin or path of destruction. It doesn’t feel like things are going in the right direction. Post-pandemic, it hasn’t brightened up hardly at all. And then there’s the internal. When you get older, there’s a sensation of twilight. Like, how much time do you have left? And music is, I think, the most reliable consolation for those types of feelings and fears and sadnesses.

I feel very, very lucky that I somehow learned how to play the guitar and express myself this way. Everybody suffers, but you’re in a better condition having an outlet like music or comedy. I don’t think it means you have more suffering than anybody else. You’ve just adapted to it in a more positive way.

There are a lot of alternate versions of me throughout the new record that I contemplate all the time, that maybe stayed in Belleville, Illinois, or got into having a hot rod car or something.

Our brains haven’t evolved to deal with the amount of information even just television gives us. I think we’re still 60, 70 years behind in terms of how human we can stay in the face of being given tons and tons of awareness of world suffering instantaneously. Whereas 150 years ago, you were very focused on the community you lived in, and the things you were aware of were things you actually had some power to change. That part of our brains is getting beaten to death every fucking day, because the natural impulse is, I want to help. When you can’t, the next thing you reach for to scratch that discomfort, that dissonance, is, Who do I fucking blame? And that’s all we do. The solutions don’t matter anymore. That’s what I’m trying to override.

I was lucky that I wasn’t that ambitious. My ambition was not How much money can I make? or How famous can I get? Those equations would have resulted in very different decisions. I tell people all the time that my wildest dream was realized when I was in my early 20s and had a record and a van and a gig to go to. I didn’t see myself on a stage in a stadium. I saw myself on a stage at Lounge Ax.

Rock ’n’ roll isn’t supposed to be conformist. If something smells in any way like it’s trying to conform, it erases an enormous amount of the appeal for me.

The best example of the idea of America, more than anything else that’s been created by America, is rock ’n’ roll. It’s a liberated art form of individual self-expression that’s very, very, very powerful and created by the least free among us. So I console myself in believing that I am participating in one of the things that is best about America. It’s an antidote to a lot of the things that are going wrong: this complete fucking debacle shitshow catastrophe that will end calamitously. But I know that this too shall pass, that some of these motherfuckers are going to be dead in my lifetime, because that’s just how it works.

There’s no human interest that is safe from a flag, from the notion of a nation-state of any kind. In my opinion, nobody should do flags. You can’t be concerned about the human condition and human welfare and be nationalistic at the same time.

My wife, Susie, has a great moral compass. I want to be a good person to feel like I deserve her. We’ve been together for 35 years — 30 married. And we haven’t drifted apart. We’ve drifted closer through the shared ups and downs of life. I can’t imagine how you would replace that kind of familiarity and comfort. She is really good at reminding me that I am an earthly figure. If a good review comes in, she’s like, “Do you need me to get the doors widened so you can get your head through?” And she’s never questioned the need for me to be on the road. She’s sacrificed an enormous amount to keep the home humming and take care of two kids by herself. To be honest, that’s why she signed up. Maybe she liked the idea of me being gone all the time.

Being there for Susie through her health issues is not something I ever saw myself as having the strength to do. But over many years of learning how to be a caretaker, it’s made me much more … I don’t know. There’s this saying that religious people have: “God doesn’t give me more than I can handle.”

Due to a series of unlikely events, I have an audience. It’s almost like a congregation. And there’s a responsibility to feel like I deserve that by trying to be a good person.

There are a lot of people who come at you that know a lot about you and have a parasocial relationship with you, and it’s very disorienting. You’re not aware of what version of you they’ve concocted. And over the years, I’ve come to the conclusion that I just have to be confident in my kindness but aware that I’m most likely not going to be able to give them what they want. Because in some cases, they want me to be their best friend.