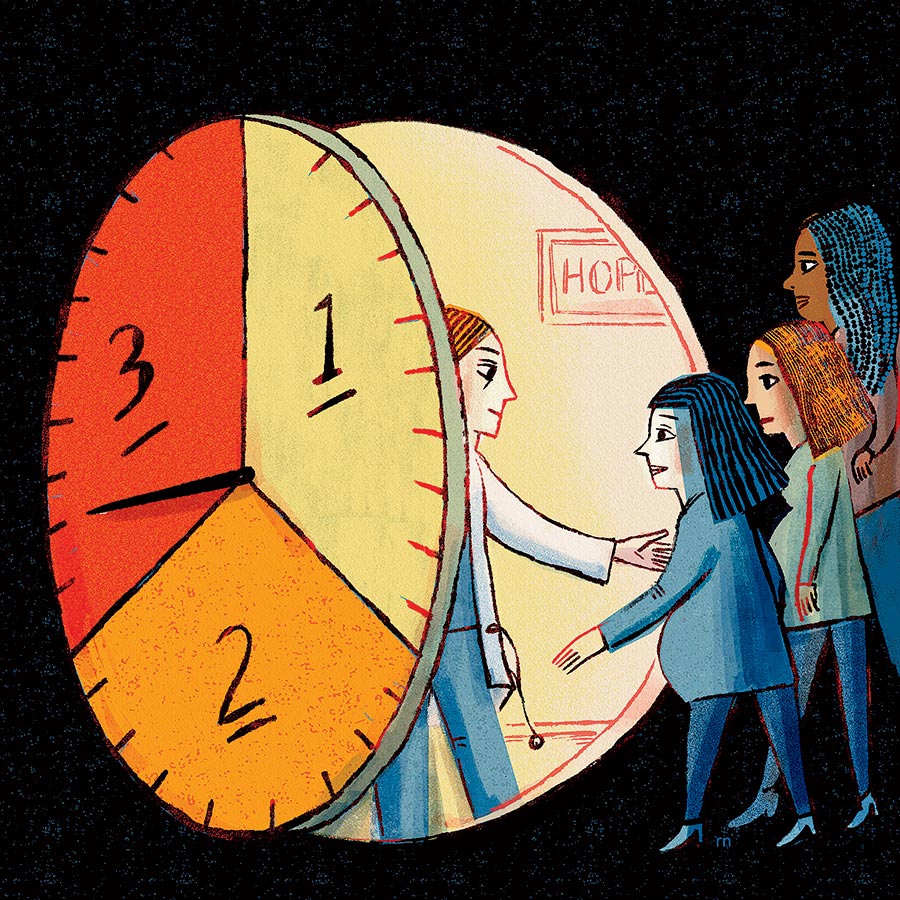

Picture an abortion clinic. Whatever comes to mind, it probably doesn’t look like Hope Clinic in Uptown. Inside the waiting room — flooded with natural sunlight, not a harsh fluorescent glare — you won’t find cheap plastic furniture or wrinkled copies of People. Patients here sit on comfortable mid-century modern couches accented in rose gold and check in at a desk next to a purple-and-sage moss wall. Rooms for exams and consultations are softly lit with pink Himalayan salt lamps glowing against exposed brick walls. Artwork lining the halls evokes the millennial girlboss aesthetic of the 2010s, with paintings of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and posters proclaiming “Women Don’t Owe You Shit.”

It’s a distinct vibe for a distinct clinic. Hope, which opened here this summer (its other location, in downstate Granite City, was founded in 1974), provides abortions up to 34 weeks into pregnancy, making it one of the few standalone clinics in the country to offer the procedure that late. “Hope Clinic is now open in Chicago, IL, expanding our care through all trimesters (And OMG we couldn’t be more excited.),” the nonprofit gushed on Instagram in June. “Everyone deserves access to abortion care, whenever they need it. Because deciding and acting on what’s best for you shouldn’t be on anyone else’s timeline.”

Well, not so fast: The state still has some say on that timeline. Or does it? Under Illinois law, abortion is allowed until fetal viability, which is generally considered to be around 24 to 28 weeks. But there is wiggle room beyond that. Doctors can perform the procedure all the way through the last trimester if they determine the abortion is necessary to protect the life or health of the mother.

And therein lies some gray area, as the law takes a wide view of what that means, citing factors “including, but not limited to, physical, emotional, psychological, and familial health and age.” In other words, the decision is ultimately between a patient and their doctor. While it isn’t difficult to envision a postviability exception when the mother’s life is at stake, what about harder-to-determine “emotional” or “psychological” health?

Hope Clinic owners Chelsea Souder and Julie Burkhart say they are following state law to the letter. “It’s really individualized, case by case,” Souder says. “It requires a conversation with our patients and our providers that looks different for everybody because of those broad circumstances that we have to take into account.”

The language in Illinois’s Reproductive Health Act, passed in 2019, dates to a landmark Supreme Court case from 1973: Doe v. Bolton, which was decided the same day as Roe v. Wade. Doe challenged Georgia’s restrictive abortion laws and expanded the definition of health beyond the mother’s physical state. With the RHA, Illinois lawmakers wanted to codify the language for the possibility that Roe would be overturned, which the Supreme Court did in 2022.

“It’s a new generation of physicians saying, ‘We are going to use our clinical judgment to the extent the law allows.’ ”

— Katie Watson, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine ethics professor

The language was purposely kept vague to give doctors the room to make the call, but they have tended to do so conservatively. “From 1973 on, most physicians did not provide as many abortions after ‘viability’ as the Supreme Court permitted,” says Katie Watson, a Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine professor who teaches medical ethics.

That’s where Hope comes in, unabashedly operating in the exception area. When I asked Hope representatives by email how the clinic determines whether it can perform an abortion after viability and how often it denies patients an abortion later in pregnancy, they declined to provide details. “Every patient is different, and every assessment is unique to their specific situation and circumstances,” the clinic responded, reiterating what Souder had said earlier.

Robin Fretwell Wilson, a professor at the University of Illinois College of Law who has studied the complex web of state abortion laws across the country, wonders if Hope would refuse to perform a procedure late in pregnancy under any situation: “I don’t see many abortion providers at Planned Parenthood or some clinic that is in this business ever really saying no to that.”

Clinics like Hope want to destigmatize not only abortion but third-trimester abortion. It’s more than just marketing: Hope’s mission is to treat as many patients as possible. Says Northwestern’s Watson: “It’s a new generation of physicians saying, ‘OK, that’s our legal latitude for serving patients. We are going to use our clinical judgment to the extent the law allows.’ ”

Part of why women seek out abortions later in pregnancy through an outpatient clinic like Hope is that hospitals are often stricter about when they will perform the procedure, usually sticking to cases where a woman’s life is in danger. Cost is another factor. A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of abortion care for individuals enrolled in employer-sponsored insurance plans found the out-of-pocket costs of “medication abortions,” those typically performed earlier in pregnancy, were similar for clinics and hospitals. However, out-of-pocket costs of “procedural abortions,” those performed later, were much higher at hospitals than at clinics: a median of $616 versus $90. Hope Clinic’s Chicago and Granite City sites don’t take private insurance, but they accept Illinois Medicaid and work with a network of 40 abortion funds to cover costs for patients who cannot pay.

As much leeway as doctors have here, some advocates argue Illinois isn’t quite the abortion-rights bastion it makes itself out to be. “We can’t really say that there is total reproductive freedom in the state, and clinics like Hope Clinic, they’re still operating under exceptions,” says Bonyen Lee-Gilmore, a spokesperson for Patient Forward, an advocacy organization focused on abortions late in pregnancy. “Patients and providers both have to justify their health care decisions through a legal, not a personal or mental lens.”

In nine states and the District of Columbia, there are no gestational limits at all on abortion, like there is in Illinois. Says Hope’s Souder: “If there are folks that maybe don’t meet the exceptions in the RHA, then, unfortunately, we aren’t able to see those people, and we work extensively to make sure that we can try to get them care outside of the state. But that doesn’t always happen, right? Because the reality is, it’s really hard and people are having to travel across the country to be able to receive care later in pregnancy.”

And for those who do meet the exceptions, some might not realize they qualify. In that sense, Watson says, Hope is providing a service by drawing attention to the option of a later abortion. Even if it means advertising it with a brightly colored cartoon flower on Instagram.