On a Thursday evening last October, Dontay Banks Sr. got a troubling call from his old friend Robert Shipp. The two had come up together on the streets of Englewood, rising through the ranks of the infamous Gangster Disciples. In the early ’90s, Banks oversaw one of the biggest crack operations on the South Side, and he selected Shipp as his right-hand man. They were sent to prison in 1994 on federal drug charges but remained close. Banks, now 56, always felt like an older brother to Shipp, four years his junior, and Shipp was like an uncle to Dontay’s children.

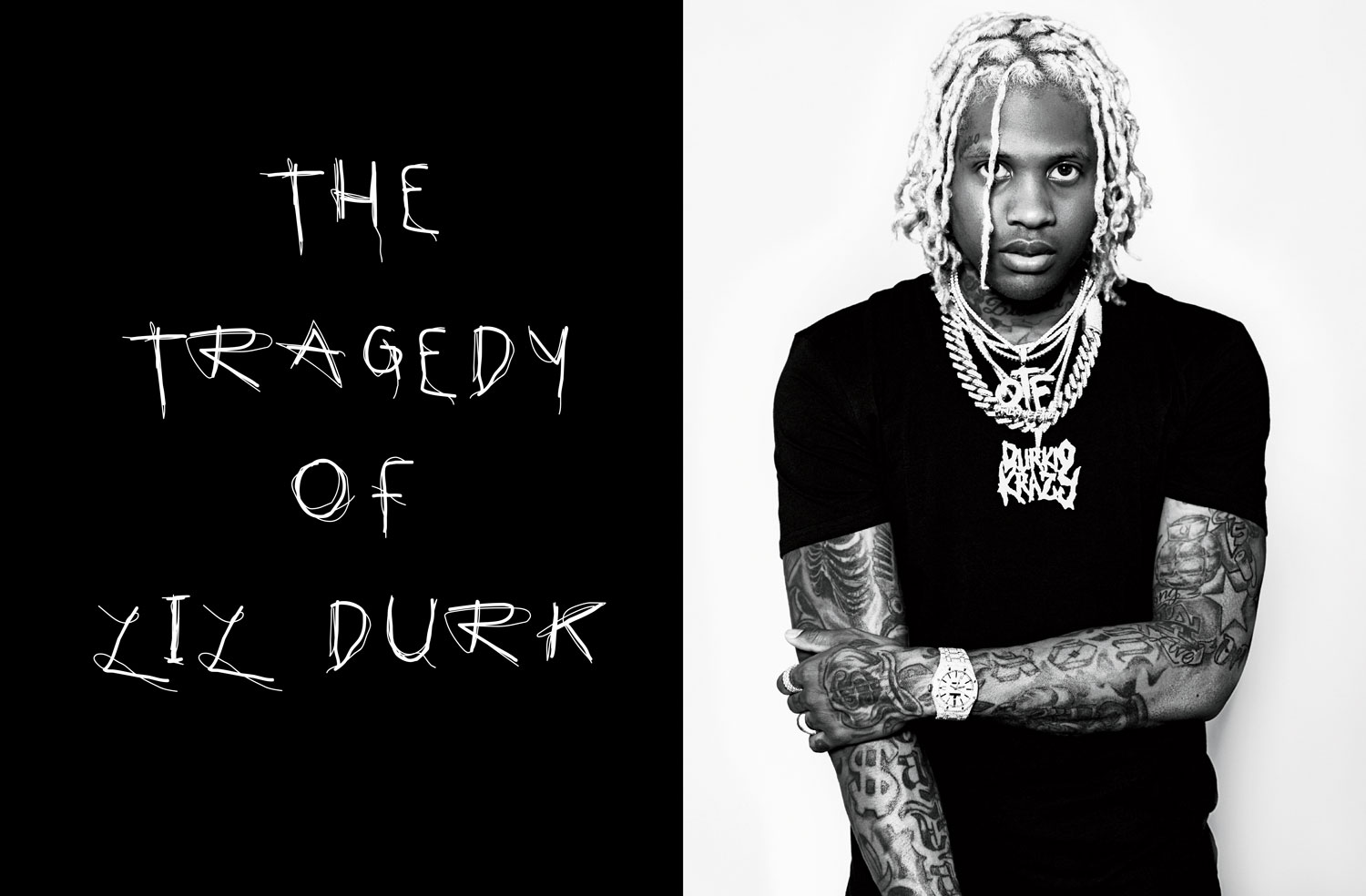

After the two got out of prison in 2019, Banks asked his trusted former lieutenant to look out for his younger son, Durk, whose career as a rapper, under the name Lil Durk, was soaring. (Dontay is the original Durk, a nickname he got in high school.) Banks wanted Shipp at his son’s side when he couldn’t be, to protect him from those trying to latch on to his fame — and to protect him from himself. Even with all his success — mansions, millions of records sold, collaborations with some of music’s biggest stars — Lil Durk maintained the edge of a Chicago street tough. He had adopted a murderous persona in songs, and allegations of real-life violence swirled around him.

Banks didn’t want to see his son follow the path he had taken. In fact, Banks was working hard to make amends for his own choices. He had come out of prison a new man with a new name, Abdul Haqq, signifying his jailhouse conversion to Islam, and started working at the antiviolence organization Chicago CRED, mentoring at-risk youths.

But on October 24 of last year, as Banks talked with Shipp on the phone, his heart sank. The feds had picked up Durk, his old friend told him. Shipp had been with Lil Durk en route to Miami International Airport when federal marshals took the rapper into custody.

Prosecutors would say later that Lil Durk was trying to flee the country. Earlier in the day, five men affiliated with Durk’s Chicago-based rap collective, Only the Family, or OTF, had been arrested in Chicago in an FBI operation. They were charged with conspiracy to commit murder for hire in a 2022 shooting in Los Angeles that targeted rapper Quando Rondo. The assailants had missed Quando in the attack but killed his 24-year-old cousin, Saviay’a Robinson.

Two weeks later, Durk would be added to the indictment. In that document, federal prosecutors portray him as something of a mob boss, running OTF as both a music label and a criminal street gang. They allege that he placed a bounty on Quando Rondo’s life and then let his associates do the dirty work. It was retaliation, they say, for the killing of Durk’s close friend and protégé Dayvon Bennett, better known as King Von. That 26-year-old rapper had been shot by a member of Quando’s entourage outside an Atlanta nightclub in 2020.

Federal prosecutors portray Lil Durk as something of a mob boss, running his rap collective as both a music label and a criminal street gang.

For Banks, the timing of the news from Shipp made it even harder to take. Durk was at the apex of his career, riding a wave of hits. Earlier in the year, he had even won his first Grammy for “All My Life,” his collaboration with rapper J. Cole. But even more significant to Banks, Durk seemed to have made it past the life of gangs and guns that had landed him behind bars several times before. He had recently returned from rehab to kick his dependence on codeine and Xanax. He was in therapy to deal with the trauma of losing so many people close to him to violence over the years. He was becoming more civically active through his charity. He had quietly married his longtime on-again, off-again girlfriend, India Royale, a fashion influencer and the mother of one of his eight children. And he had come to more fully embrace Islam, the religion that had changed his father’s life.

Just days before the arrest, Durk, who had left Chicago years ago — he has houses in Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Miami — came back home to celebrate his 32nd birthday. It was a triumphant return. That weekend, Durk accepted honorary keys to the city from west suburban mayors Katrina Thompson of Broadview and Andre Harvey of Bellwood — something that would have seemed unfathomable earlier in his life.

Now, though, he sits in a federal detention center in Los Angeles, awaiting a trial that could dramatically change the trajectory of his life. Because this a complicated case with so many defendants, his trial has been pushed back twice already. It is now scheduled to start January 20. Durk, who declined to be interviewed for this story, has denied the charges against him.

This isn’t the only legal trouble he’s facing. Court records unsealed last December, as part of the legal proceedings regarding whether Durk should be released on bail, show that the FBI is investigating his possible connection to another killing: the 2022 death of 24-year-old Stephon Mack, shot by two masked gunmen as he walked out of the Youth Peace Center of Roseland on Chicago’s Far South Side. According to those records, authorities suspect that Durk bankrolled the hit as retaliation for the killing of his older brother, Dontay Banks Jr., less than eight months earlier. Two men allegedly associated with a Chicago gang were charged in Mack’s death, and investigators say they found text messages that link them to Durk and OTF.

Durk may have left Chicago and tried to transform himself, but the life he led here has followed him. His impending trial will answer a question that has dogged Durk throughout his career: Did one of the world’s biggest rappers ever stop being a gangbanger?

Sitting in a Chicago CRED office on the Far South Side, dressed in a bright white tracksuit and white crocheted skullcap, his bushy black beard marked by a thick white streak, Dontay Banks Sr. expresses some guilt as he talks about the events that have unfolded. One of his sons is dead. Another faces the possibility of growing old in prison, the way he did. It eats at Dontay that he was behind bars when his sons were growing up, when they needed him most: “Had I been more responsible and been out there, then I could’ve took my role on as a father and been able to navigate them through life in Englewood.”

Barely a year old when his father was sent to prison, Durk Banks grew up in a faded yellow-brick three-flat at 7220 South Halsted Street owned by his maternal grandmother. Hattie Woodard, who was a cleaner at O’Hare, bought the building for $10,000 in 1962 and struggled to hang on to it for years, fighting off liens for missed mortgage payments and outstanding bills. During Lil Durk’s youth, the block was full of empty lots and dilapidated homes and boarded-up businesses.

His mother, LaShawnda Woodard, and her three children, all by Dontay, shared the three-bedroom second-floor unit with her mother, along with a gaggle of other relatives — 10 people altogether. Dontay Jr. slept on a couch. Durk slept on the floor.

Money was tight. LaShawnda got by on food stamps and public assistance, and for a brief time she sold crack, as she relates in the 2020 memoir she self-published. In an interview with Vibe, Durk recalled eating a lot of rice and toast. Some nights, he went hungry.

Durk’s father did the best he could to parent in absentia, but he had just 15 minutes of phone access a day in prison to dole out guidance. To his sons, he harped on a familiar theme: Don’t repeat my mistakes.

Dontay Banks Sr. did the best he could to parent in absentia, but he had just 15 minutes of phone access a day to dole out guidance. To his sons, he harped on a familiar theme: Don’t repeat my mistakes. That was a tough sell. Lil Durk had heard the stories about his father. Everyone in the neighborhood knew him. During his heyday as a gang leader and drug kingpin, his crack operation, court documents show, took in upward of $15,000 a day. Durk mythologized his dad and held fast to that idealized version. “Ain’t gonna lie, I wanted to be just like him,” he told YouTube interviewer DJ Vlad years later. “All the cars, all the bitches, all the furs, all the clothes.”

He emulated his father’s old ways. As LaShawnda recounts in her memoir, when Durk was 9, a neighbor showed up at the door, very late at night, holding him by his shirt collar in one hand and a handgun in the other. It was LaShawnda’s.

“Well, your son had it,” the man said, adding that the boy had tried to stick up a Harold’s Chicken.

By 10th grade at Paul Robeson High School, Lil Durk had all but stopped going to class and started getting into trouble with the law. He was arrested for relatively petty crimes: breaking into cars and trespassing. His older brother, like their father, had as a teen joined a neighborhood gang: a faction of the Black Disciples known as Dog Pound. Durk soon followed him into the life but gravitated to the Lamron faction, which claimed the turf between 59th and 67th Streets, from the Dan Ryan Expressway to Normal Avenue (“Lamron” is “Normal” spelled backward). The gang had a reputation for violence. A 2013 Sun-Times story reported that Chicago police considered Lamron to be “public enemy No. 1” in Englewood.

Dog Pound and Lamron members dealt drugs and waged turf wars, just like the gangbangers of old, but these new types of gangs lacked a rigid structure. During the tough-on-crime period of the ’90s and the early 2000s, law enforcement had gotten so effective at locking up gang leaders that the hierarchies across the city effectively crumbled. By the mid-2000s, when Dontay Jr. and Lil Durk got involved, the top-down sprawling systems — with chiefs and armies of foot soldiers — had been replaced by fractured cliques, which were typically aligned with particular blocks or housing projects and had little to no formal power structure.

The new generation was more interested in competing for likes and shares on social media than for drug turf. To these cliques, attention was currency, and by making rap music and using platforms like SoundCloud, Twitter, and YouTube, they could monetize it. With this new focus, rappers, rather than drug kingpins, became the gangs’ principal figureheads. Members propped up and protected the rappers who had the most juice. The rappers, in turn, hyped up their affiliations in their music and waged wars of words with rival gangs.

Encouraged by his brother and his brother’s friends, Durk started rapping. He needed little convincing. He hungered to make a name for himself in the neighborhood, like his father had done. “My daddy a legend in these streets,” he’d later say. “I want to be a legend inside this music, and I want everybody to remember my name.”

Around this time, a new hip-hop sound was bubbling up on the South Side. It emulated the Southern-style trap music of the early 2000s, which glorified drugs, sex, and money. But Chicago rappers and beatmakers were giving it a twist. They gave the music — which came to be called drill, slang for killing a rival — a fresh, if more aggressive and menacing, energy. The lyrics, too, were angrier. Instead of filling their songs with the braggadocio about money, cars, and women so familiar in mainstream rap, they wrote unflinchingly about the realities of street life and unapologetically about acts of violence they claimed either to be responsible for or to know about. They made cheap music videos with their friends, throwing gang signs, wielding guns, smoking blunts, and flashing money.

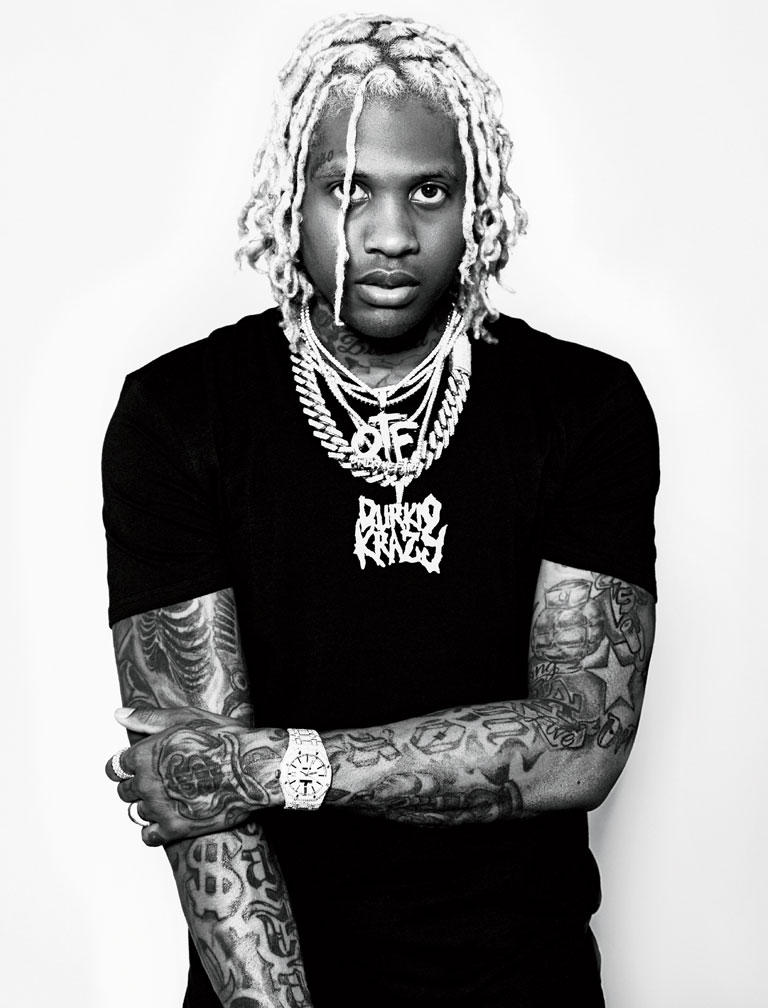

Lil Durk was a natural, recalls Duan Gaines, a producer known as DGainz, who made videos that became hits for several big drill artists early in their careers. Durk had the swagger and charisma of a star in the making, and the look, too, with his long dreads and his neck, arms, and hands covered in tattoos. “He had the appeal, the way he carried himself,” says Gaines.

He also had unmistakable talent. He was a dexterous freestyle rhymer, and his singsong rapping style, enhanced with Auto-Tune, stood out. He combined tough-talk lyrics with melody and catchy hooks — a combination that broadened his appeal beyond the largely male fan base drawn to drill.

In April 2010, at the age of 17, Durk had his first local hit, “Lamron Wasted,” a freestyle tribute to his gang. That same year, he and Dontay Jr. helped form the collective of rappers known as Only the Family. Durk continued to put out songs, and in 2011 he released the track “Sneak Dissin’.” “The publicity from that made me start to take rap serious,” he’d later say. He followed up with his biggest hit yet, “I’m a Hitta,” which racked up 300,000 views.

That October, a week before his 19th birthday, Durk was arrested. Officers were looking for him as part of an investigation into the shooting of four teenagers on a Woodlawn porch. According to the police report, officers spotted Durk running into the gangway of a building, carrying a semiautomatic handgun that they say he stashed behind the rear wheel of a parked car. He was charged with multiple gun-related felonies.

Durk was in detention for more than three months and missed the birth of his first child, Angelo, with his high school girlfriend, Nicole Covone. He was released on bond just as the city’s rap scene started to explode.

In March 2012, a 16-year-old named Keith Cozart, who rapped as Chief Keef, dropped a video for his track “I Don’t Like” on YouTube. The no-frills, raw footage featured snippets of Chief Keef, mostly shirtless, bouncing around his grandmother’s kitchen and living room with members of his rap collective, Glory Boyz Entertainment, and other buddies from O-Block — a Black Disciples set. They smoke blunts, flash gang signs, and point two-finger guns threateningly at the camera.

The video instantly went viral. Without a label’s publicity machine behind it or nationwide radio airplay, “I Don’t Like” reached No. 73 on the Billboard Hot 100, boosted by a Kanye West remix, which helped take the song — and drill — worldwide. Keef would go on to sign a reported $6 million deal with Interscope.

Major record labels flocked to Chicago to find more rappers like him. The music website Pitchfork would later call it the “Great Chicago Rap Gold Rush.” King Louie signed with Epic Records, Young Chop with Warner, and G Herbo with the Chicago-based label Machine Entertainment Group.

Around this time, Durk had a breakthrough hit with “L’s Anthem,” a chest-thumping track dissing the rival Gangster Disciples, which got local radio play. His “I’m a Hitta” mixtape had already caught the attention of Ernest Dion Wilson, the prominent Chicago producer and DJ known as No ID. Wilson had mentored a teenage Kanye West and produced Common, Jay-Z, and Rihanna and had recently joined the Island Def Jam Music Group. Wilson inked Durk to a deal that paid him a $150,000 advance for a first album. There was an option for four more albums, with increasing royalty rates, with the last one potentially earning Durk $525,000 to $1.05 million.

Although he now had a six-figure contract, Durk was still living in his grandmother’s apartment, his mind still on the streets. “Unfocused, lost,” he later recalled to Rolling Stone. “Thinking about gangbanging.”

Six days after signing his record deal, in April 2012, Durk pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of aggravated unlawful use of a weapon in the case from the previous October. The judge, Vincent Gaughan, who, six years later, would preside over the murder trial of the police officer who killed Laquan McDonald, sentenced Durk to a year in prison, but with the time he’d already served, plus early release, he was out on parole in three months.

He went right back to the studio, and that October he released Life Ain’t No Joke, his third mixtape and first since signing with Def Jam. The tape received mixed reviews, but it showed a 20-year-old artist coming into his own and doing things his way, like leaning on Auto-Tune, which was rare among drill rappers.

As drill culture was rising, Chicago was experiencing an alarming spike in murders. It had 506 homicides in 2012 — more than any other city in the nation. Mayor Rahm Emanuel and police officials contended that drill songs and videos and social media postings weren’t just chronicling the tit-for-tat violence but also fostering it.

As proof, they pointed to the killing that year of an 18-year-old rapper named Joseph Coleman, who went by Lil JoJo. He belonged to a Gangster Disciples faction called Brick Squad that had been feuding with Durk’s Lamron and Chief Keef’s O-Block, which together formed a Black Disciples coalition known as 300. Durk’s “L’s Anthem” had included the line “Brick Squad, I say fuck ’em.” Lil JoJo had countered with “3HunnaK (BDK)” a diss track in which he declares himself a BDK, or Black Disciples Killer. Pointing guns in the accompanying video, he raps: “Durk says ‘Fuck Brick Squad,’ so I can’t wait to catch ’im. Squeeze this fuckin’ .40, now they got him on a stretcher.”

Knowing that beefing with two of the city’s best-known drill rappers would elevate his profile, Lil JoJo continued to ratchet up the provocation even after he was shot at but not hit. In September 2012, he posted a video of himself driving through a Black Disciples neighborhood, where he encountered Durk’s friend Tavares Taylor, a prominent rapper known as Lil Reese who was affiliated with the gang. Reese and JoJo shouted threats at each other. Hours later, Lil JoJo was killed in a drive-by while riding his bike in Englewood. Black Disciples members mocked his death on social media.

Violence between the Black Disciples and the Gangster Disciples had been a regular occurrence for decades. But Coleman’s killing, which remains unsolved, intensified the conflict. “It got kind of grim,” recalls Gaines, the video producer, who worked with rappers from both gangs. The music had always “come from a dark place,” he explains, “but a lot of it was still fun.” Now the separation between music and violence, between inspiration and incitement, was blurred. “After JoJo it bled into each other.”

In spite — or perhaps because — of this, drill rap attracted more and more attention well beyond Chicago. Coinciding with its rise was the emergence of an internet spectator culture that followed both the music and the violence that came along with it. This cottage industry of news sites and fan pages and blogs and message boards covered these rap beefs like the story lines of WWE wrestling. Song lyrics and music videos were dissected to identify references, disses, and Easter eggs. The rappers frequently appeared on vlogs and podcasts and posted on social media, fanning the flames themselves.

The more Durk touted his gang affiliations in his music, and the more prominence he gained on the streets, the more attention he drew from the police, who had begun monitoring the social media accounts of suspected gang members. One very early morning in June 2013, he was arrested again. Responding to a call about a man with a gun, police officers arrived at 72nd and Green Streets, the heart of Dog Pound’s turf. According to court records, officers saw Durk toss a Glock into a car. That gun, it turned out, had been reported stolen.

Just weeks from finishing parole on his 2012 gun conviction, Durk was back in jail. But not for long: This time he had the money to hire one of Chicago’s highest-profile criminal defense lawyers, Sam Adam Jr., who had previously represented the likes of Rod Blagojevich and R. Kelly and whose father had helped Durk’s father beat a murder case two decades earlier. Adam provided sworn statements from nine eyewitnesses saying the gun wasn’t Durk’s. After 43 days locked up, Durk was released on $100,000 bond.

Durk would later plead guilty to two felony gun charges and get 18 months’ probation and no further time behind bars. After the sentencing, he assured the Chicago Tribune he wouldn’t be appearing in criminal court again: “The key word is I’ll be staying out of trouble. You can put a capital ‘N’ — for never.”

Durk came home right around the time Covone gave birth to their second child, daughter Bella. And again, he went right back to work recording his next mixtape.

LaShawnda was delighted that her son was achieving success, but she worried about the violence that seemed to go hand in hand with the music. In her memoir, she recounts being at a grocery store dressed in a T-shirt emblazoned with the title of Durk’s single “Dis Ain’t What U Want,” a song in which he seems to mock JoJo’s death.

A couple of teenage boys approached her. “Yo, you know him?” one of them asked in a menacing tone, pointing to her shirt.

LaShawnda played dumb, shaking her head and saying the shirt belonged to her daughter.

When she told Durk what had happened, he told her she shouldn’t wear the shirt out in public. He didn’t elaborate, but she quickly figured it out: “My son had enemies.”

Dontay Sr. had concerns about Durk’s rapping too, but for more practical reasons. He was unconvinced that Durk could make a living off it. With only limited internet access in prison, he couldn’t see how drill rap was exploding in popularity. He was also in the dark about all the gang happenings. On their calls, neither Durk nor Dontay Jr. volunteered much information. “When I talked to them, they were almost like church boys,” Dontay Sr. remembers with a chuckle. “I’m not getting the real deal about what’s going on.”

The steady drumbeat of bloodshed soon reached Lil Durk’s family. In May 2014, McArthur Swindle, one of his cousins, was sitting in an SUV in a parking lot of a strip mall in Chatham when someone approached the 21-year-old and started shooting. Swindle was struck multiple times, and as he tried to drive away, he crashed into a storefront window. He bled out at the scene. The two cousins had grown up together at their grandmother’s apartment on Halsted, and Swindle was just starting to break into rapping with OTF. A few days before, the video for “OC,” his collaboration with Durk, had dropped.

Swindle’s killing, which remains unsolved, set off frenzied speculation on the internet. The consensus: It almost certainly had to do with an escalating war of words between Swindle and rival gang members. In a Twitter exchange with rivals days before he was murdered, Swindle tweeted that he was going to kill a Gangster Disciples rapper affiliated with a crew from Woodlawn.

Durk’s mother was at a grocery store dressed in a T-shirt emblazoned with the title of his recent single when a couple of teenage boys approached. “Yo, you know him?” one of them asked in a menacing tone, pointing to her shirt. She quickly figured it out: “My son had enemies.”

Durk was only 21, but death had already become a constant in his life. Asked in an interview after Swindle’s killing about how many friends he’d lost, Durk replied grimly, “Probably 20 — 20, 30 people.”

That July, Durk released his mixtape Signed to the Streets 2. But just a few months later, he was in trouble again. Early one morning that November, Chicago police investigators showed up at the townhouse Durk was renting in suburban Orland Park. They were looking for a friend of Durk’s who was staying with him, according to court records.

As the officers took the friend, who was wanted in connection with a homicide, into custody, they noticed two handguns out in the open. They seized the Glock .45-caliber and Springfield .45 and arrested Durk, too. According to the police report, Durk told officers that he had the guns because people were trying to steal money from him. He was charged with multiple gun felonies for violating his probation. Though Durk was released on bond, the case would linger for nearly two more years.

Then, less than a year after the killing of his cousin, tragedy struck close to home again for Durk. In March 2015, his 24-year-old manager, Uchenna “Chino” Agina, an original member of his OTF inner circle, was killed as he sat in his parked car in front of an all-night sandwich shop at 84th Street and Stony Island Avenue. Hours before his killing, Agina had posted on social media Durk’s remix of Chief Keef’s track “Faneto.” In it, Durk issues an ominous warning to another gang: “Bitch, I’m ridin’ through the opps / Finna go and shoot Young Money up.”

Agina’s killing, which has not been solved, hit Durk hard. His rival rappers mocked the death. One, a man named Ronald Crump who rapped as Mubu Krump, live-streamed himself picking up carryout at the restaurant where Agina was killed. His order: a “Chino” burger, placed under the name “Nuski,” a nickname of Durk’s slain cousin. (In 2018, Mubu Krump himself would be shot dead at a party, and Durk would celebrate his death in the song “Back in Blood”: “He was dissin’ on my cousin, now his ass all in that wood, huh?”)

Though Durk was putting out a steady stream of music through all of this, his career started to stall. By now, the novelty of Chicago drill had worn off, and variants in Brooklyn, London, and Paris seemed fresher. The industry’s spotlight had largely shifted back to Atlanta’s newest generation of trap artists.

Durk got some much-needed new heat in June 2015, when Def Jam released his debut studio album, Remember My Name. It was the first album by a Chicago drill rapper on a major label since Chief Keef’s debut, two and a half years earlier. It reached No. 14 on the Billboard 200.

As his star began rising again, Durk acquired the trappings of wealth, including a house in the suburbs, cars, designer clothes, and jewelry. His mother now had her own apartment, and Durk paid her rent and even bought her a Lamborghini. (It was too flashy for her, and she gave it back in exchange for a Chevy Tahoe.) “He had more money than he knew what to do with,” she writes. The problem was, she adds, the more money Durk made, “the more problems that came with it.”

TRAIL OF BLOODSHED

HIS ORBIT

HIS OPPS

One way to avoid trouble, Durk concluded, was to leave Chicago. In early 2017, just a few months after prosecutors dropped the charges related to the Orland Park arrest (a judge held that the prosecutors hadn’t proved Durk had been in possession and control of the guns), Durk moved to Alpharetta, Georgia, a tony suburb north of Atlanta. “I had to get away from what was going on in Chicago,” he later told Brick magazine. Besides, Atlanta had become the epicenter for rap. There, Durk could collaborate with like-minded artists and new producers who could help him evolve and elevate his sound to become more mainstream and radio friendly.

But Durk and his traveling entourage of Black Disciples pals wouldn’t be getting an entirely fresh start down south. A Chicago police gang investigator sent an email to colleagues in Atlanta with a warning. His message, as he would later describe it in court testimony, was “just, like, an FYI: ‘Here they come, here is what they are involved in here, and if you see any of this activity, contact us, and we’ll see if we can assist you.’ ”

Among those who came with Durk to Atlanta was Dayvon Bennett, a childhood friend who was affiliated with O-Block. Bennett had spent most of his life in legal trouble. He had felony convictions for guns and theft. In 2017, he beat murder and attempted murder charges in connection with a 2014 triple shooting at an Englewood home. He frequently made thinly veiled boasts on social media that he had several homicides under his belt.

Encouraged by Durk, Bennett began rapping in jail, calling himself King Von. Durk recognized the potential of his vivid storytelling style and his gun-toting image and signed him to his OTF label. The two began an almost brother-like partnership. Musically, Durk and King Von were an efficacious one-two punch: Durk’s melodic touch softened his friend’s hard edges; Von’s aggressive storytelling complemented Durk’s emotive vocals. But King Von was just the sort of trouble magnet Durk insisted he was trying to get distance from. While Durk now had one foot in and one foot out of the gang world, Von was still neck-deep in it.

Durk was energized by his new life in his new town. He dropped four mixtapes in 2017 alone, and in 2018 he released his third studio album — this one under Alamo Records. Durk was also busy expanding OTF beyond music, starting a clothing line and even forming a real estate company to flip houses. And he had a new love interest: India Cox, who went by India Royale, a model and influencer from Chicago.

There were other life changes, too. Sometime around 2018, Durk and Dontay Jr. told their father, still incarcerated, that they wanted to convert to Islam. Dontay Banks Sr. had converted in prison as part of his break with gang life. Durk and his father spoke almost daily over the phone, and during their conversations, Banks had talked a lot about his faith and how it had given him the inner strength to overcome adversity and had completely changed his outlook. It had made Durk curious. He and his brother went to see their father at the federal prison in Milan, Michigan. In the visiting room, Dontay held the sacred conversion ceremony, in which his sons both recited the Shahada, the Muslim declaration of faith. Robert Shipp gave Durk the Muslim name Mustafa Abdul Malik.

Even as Durk tried to make both a spiritual transformation and a new life in Atlanta, violence continued to plague his family in Chicago. In October 2018, Dontay Jr. was struck multiple times by gunfire in Pullman. He survived, but their 30-year-old cousin, Darnell Banks, was killed in the barrage. Not even six months later, Durk would lose another cousin: 23-year-old Antwon Fields, who rapped under the name Lil Mister. He was walking in Englewood when a car slow-rolled by and a passenger shot him in the head.

But while Durk and Lil Mister were related by family, they were opponents — “opps” — on the street. Lil Mister, a drill pioneer and a member of a Gangster Disciples set, had even dissed Durk directly in one of his early tracks. Days before his death, he’d reportedly taken to social media to taunt a rival rapper named Memo600, who at the time was part of OTF.

Durk’s Chicago troubles finally caught up with him on his new turf in early 2019. It was Super Bowl weekend, and the game was being played in Atlanta. At a recording studio, Durk ran into a friend from home, rapper Ameer Golston, who went by AAB Hellabandz, and another man from Chicago, Alexander Weatherspoon. Along with King Von, they all spent the night caravanning around the city in SUVs before arriving at the Varsity, a popular hot dog stand, the next morning.

According to court documents, surveillance video showed the group hanging out in the parking lot for 45 minutes. Then, around 5:45 a.m., a fight broke out inside the SUV that Weatherspoon was driving. Weatherspoon would later tell the police that Golston had taken his gold chain and stolen $30,000 from him. Durk and Von, witnesses told police, leaped out of their Jeep and started toward the other vehicle, and Durk allegedly pulled out a gun. Surveillance video showed Weatherspoon opening his car door, followed moments later by a muzzle flash and Weatherspoon limply running across the street. Police say the video shows Durk returning to the Jeep and allegedly shooting at Weatherspoon while driving, as Von fired at him from the sidewalk. Weatherspoon collapsed when a bullet hit an artery in his leg but survived, and Durk and Von drove off.

After a three-month investigation, arrest warrants were issued for Durk, Von, and Golston. Von was arrested in Chicago. But before Golston could be taken into custody, he was shot and killed in Miami after Durk’s performance at the Rolling Loud music festival there that May.

A couple of weeks later, Durk, who was on tour, canceled his upcoming concerts and flew back to Atlanta to surrender to police. Television cameras followed the rapper, wearing a gray Nike sweatsuit, his dreadlocks dyed blond, as he entered the Fulton County Jail. A master at leveraging even negative media attention into new opportunities, Durk released a song titled “Turn Myself In,” in which he professed his innocence and presented himself as the victim of “false accusations” by prosecutors targeting him because of his fame.

With his old friends in his new orbit, Durk hadn’t left Chicago as much as he had taken Chicago with him to Atlanta.

Durk and Von were charged with attempted murder, aggravated assault, and illegal possession of a firearm, as well as participating in gang activity. Interviewed by a local TV news station before surrendering, Durk denied being involved in a gang, saying that was in the past. “I had a bad background just growing up as a child, and my father being incarcerated for 25 years, 26 years,” he explained. By moving to Atlanta, he went on, “I just thought that it changed my whole identity of thinking.” But with his old friends in his new orbit, Durk hadn’t left Chicago as much as he had taken Chicago with him to Atlanta.

Durk and Von were denied bail. At the preliminary hearing two weeks later, prosecutors wouldn’t play or share any of the video footage that they say showed Durk and Von firing, according to Manny Arora, the Atlanta attorney who represented Durk in the case. Under questioning, an Atlanta police detective conceded that surveillance video showed Weatherspoon also had a gun that night. He also acknowledged that, during the struggle in the car, it was possible that Weatherspoon may have even fired the first shot.

A week later, Durk was granted bail and released; shortly afterward, Von was too. “I’m baccccccccckkkkkk,” Durk announced on Twitter. Just a few weeks later, his father was also a free man, having been released from prison.

You’d think an attempted murder charge would be a public relations nightmare for a celebrity. But the parade of headlines and social media coverage only boosted Durk’s popularity. “It put him on the map,” says Arora. The video for “Turn Myself In,” for instance, racked up more than 34 million views. Nicki Minaj, Travis Scott, DJ Khaled, and other prominent hip-hop artists were lining up to work with Lil Durk.

Durk parlayed this attention into a musical hot streak. His next album, Love Songs 4 the Streets 2, released just weeks after he got out of jail, hit No. 4 on the Billboard 200, his highest-charting album at the time. The deluxe version of his 2020 follow-up, Just Cause Y’all Waited 2, reached No. 2, and within six months it would be certified double platinum. That August, Durk and Drake, perhaps hip-hop’s biggest artist, collaborated on the single “Laugh Now Cry Later,” which debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. 1 among streaming songs. It was Durk’s biggest hit yet, and it helped him attract a broader crossover audience.

By this point, most of the first wave of Chicago drill rappers had flared out. Even Chief Keef, drill’s early sensation, had moved to Los Angeles but rejected the mainstream music industry for a straight-to-YouTube DIY approach. Durk, though, thrived, winning the praise of critics and executing savvy collaborations with both up-and-coming rappers and radio-friendly artists. He celebrated by buying a $1.15 million eight-bedroom mansion in Château Élan Estates, a gated community in Braselton, Georgia, an hour from downtown Atlanta.

But despite his career reaching new heights, there would soon come allegations that Lil Durk was still up to his old gang ways.

Late in the afternoon of August 4, 2020, 26-year-old Carlton Weekly was shopping with his girlfriend in the Gold Coast. The prominent drill rapper, who went by FBG Duck, was standing in line on the sidewalk in front of the Dolce & Gabbana store when two vehicles pulled up. Four masked men jumped out and started shooting, firing 16 shots and killing him. His girlfriend and another man were wounded. Six members of O-Block would later be convicted of the murder in a racketeering conspiracy case. (A seventh suspected participant took his own life during the investigation.) Documents presented at the trial revealed that an FBI informant claimed that King Von had put a $100,000 bounty on FBG Duck and had paid $128,000 to buy several of the hit men diamond-encrusted O-Block pendants.

For years, Von and Durk and other members of O-Block and OTF had been feuding with the Fly Boy Gang, a rap group affiliated with the Gangster Disciples, and the GD’s Tookaville faction, with which FBG Duck was aligned. As far back as 2013, Durk had seemingly threatened to kill Duck, rapping in his song “Competition” that “Lil Duck, he can’t duck this clip.” Likewise, FBG Duck taunted Durk and Von, calling out Durk as being a phony gangster, questioning his toughness and street cred, and dissing McArthur Swindle, Durk’s deceased cousin. And then in 2017, one of Von’s closest friends, James Johnson, a 23-year-old who went by T-Roy, was fatally shot inside a convenience store. That ignited a new cycle of killings — and rap disses.

The dissing didn’t stop with FBG Duck’s death. Durk seemingly alluded to it in a song he released in early 2021 called “Should’ve Ducked.” When Lasheena Weekly, the slain rapper’s mother, heard it, she furiously denounced Durk on social media, accusing him of trying to profit off her son’s killing, even raising the possibility that Durk was responsible.

Last October, Lasheena filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Durk and others on behalf of her son’s estate. In the suit, she asserts that Lil Durk knew of Von’s $100,000 bounty and that he “actively participated to have FBG Duck killed and/or to cover up the killing.” The suit also takes on the record industry, naming Alamo Records — Durk’s current music label — and Sony Music Entertainment, its parent company, as defendants. The suit claims they were negligent in promoting and profiting from diss tracks that fueled violence.

Even with the attempted murder case hanging over him, Durk kept the hits coming. Before the end of 2020, he would release five more singles that charted on the Billboard Hot 100. In September, the month after FBG Duck’s murder, he dropped the track “The Voice.” It was a statement song in which he declared himself “the voice of the streets.” The message: No matter how big he had gotten, no matter how broad his audience had become, he hadn’t forgotten where he’d come from.

He started putting his money where his mouth was. In 2020, Durk and OTF established the charitable organization Neighborhood Heroes Foundation to contribute to underprivileged neighborhoods like the one where he grew up. Initially, the public relations boost for Durk was arguably bigger than the foundation’s impact. Tax records from 2020 show that the charity had gross receipts — mostly contributions and gifts — of just over $17,000. When the pandemic hit, the charity handed out a couple hundred hot meals to frontline workers at Mercy Hospital in Chicago. It provided new sports clothes and shoes to a hundred kids in an Atlanta Boys & Girls Club. It threw a back-to-school block party in Englewood, passing out supplies, personal hygiene products, and electronics. And it held a voter registration drive.

To Banks, Lil Durk’s legal problems feel full circle. It “hurts real bad,” he says, that his son is now, like he had been, caught in the crosshairs of the federal government.

While Durk seemed to be refocusing on his music and reshaping his public persona, King Von seemed to be itching for another fight — one that would ultimately cost him his life. With FBG Duck out of the picture, Von, whose rap career was beginning to soar, started taking unprovoked shots at Kentrell Gaulden, a Louisiana rapper known as YoungBoy Never Broke Again or NBA YoungBoy, and Tyquian Bowman, who went by Quando Rondo and had just signed with YoungBoy’s imprint.

Only a couple of years earlier, Durk and NBA YoungBoy had collaborated on the track “My Side.” But by 2019, as NBA YoungBoy’s popularity grew, Von started trolling him on social media. Both rappers traded taunts in their songs.

On November 6, 2020, Von and Quando ran into each other outside an Atlanta hookah lounge and got into a brawl in the parking lot. Their entourages joined the fray. Guns were drawn and six people were shot, two fatally: King Von and another Chicagoan, Mark Blakely, a 34-year-old who was reportedly affiliated with O-Block and had ties to OTF.

Surveillance video shows Von lying on the ground, his white T-shirt bloodstained. Friends load his limp body into a black car and transport him to the hospital. He was 26 and a father of two, with a third on the way. Just a week earlier, his first studio album, Welcome to O’Block, had been released to critical and popular acclaim.

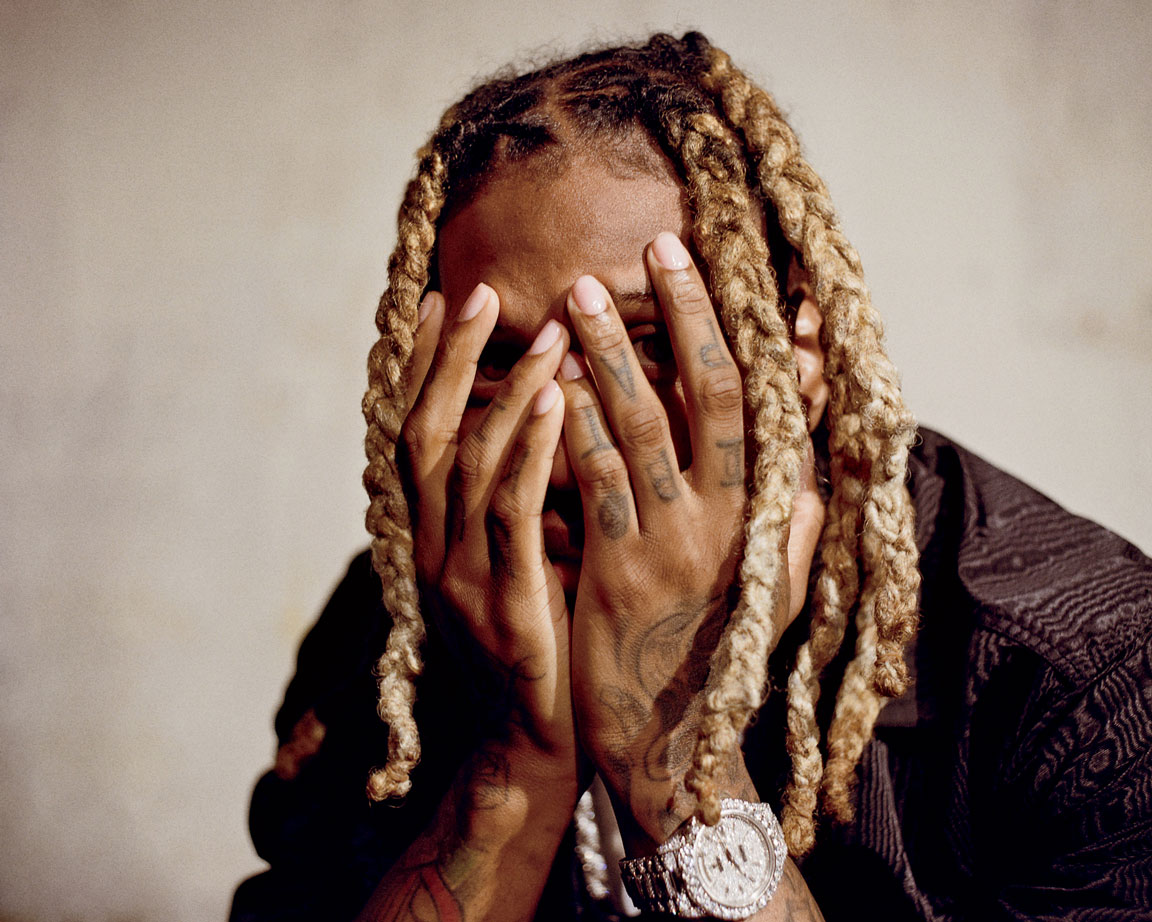

Durk wasn’t with Von the night of the fatal run-in; they were legally prohibited from communicating with each other while their attempted murder case was still pending. But he wrote of his friend on Instagram: “MY TWIN GONE.”

Almost immediately, Von’s killing had fans and various corners of the hip-hop universe speculating and chattering about whether Durk would, or should, retaliate. Daniel Hernandez, the Brooklyn-based rapper known as 6ix9ine and a notorious internet troll, goaded him to seek revenge. “When is durk going to slide for von?” he posted. He went on to question his street toughness and loyalty. “Nuski now von AND you still rapping go pick up a gun,” he wrote on Instagram, with five laughing-crying emojis. Durk deactivated his Instagram account the next day and stayed off the platform for more than a month. He signaled his return in late December by posting a photo of himself wearing King Von’s signature O-Block chain with the hashtag #DOIT4VON in the caption.

Do what? the internet wanted to know.

A few weeks after King Von’s death, a rumor spread on the internet that there was a $1 million bounty on Quando Rondo. Quando addressed it in a song. “Million on my head, that’s what they say,” he raps in “End of Story.” “That’s all you got? Bitch, make it eight.” Bravado aside, for months he had to cancel his live concerts because of security concerns and was forced to do virtual shows.

Even as pressure mounted on Durk to retaliate, his career kept climbing. In June 2021, he released The Voice of the Heroes, a collaborative album with Lil Baby, one of Atlanta’s hottest rappers. The record topped the U.S. charts, marking Durk’s first No. 1 album. In the first half of that year, 33 of his songs — either his own or ones he was featured on — charted on the Billboard Hot 100, more than for any other artist.

Two days after the album dropped, Durk suffered another devastating loss: Shortly after midnight on June 6, his brother, Dontay Jr., who was 32, was fatally shot in the head during a wild gunfight outside the Club O, a strip club in south suburban Harvey. Dontay Banks Sr. called Durk, who was performing in Orlando, to break the news. “I told him he didn’t make it, you know, and then, so …” Banks’s voice trails off as he remembers the day.

Details of the incident remain elusive, and the case remains unsolved. The City of Harvey declined to provide copies of the police reports, citing the ongoing investigation. A city spokeswoman who briefed reporters after the shooting made it sound at the time as if Dontay had been caught in crossfire.

Chatter on the internet suggested that Durk’s brother was killed by a member of the Gangster Disciples — a suspicion that is shared by law enforcement. According to court documents, a confidential informant told the FBI that Dontay was shot by members of Dump Street, a GD faction affiliated with the gang’s Smashville clique.

Dontay’s death came seven months to the day after Durk lost his close friend Von. Soon there would be an apparent attempt on Durk’s life as well: In the early hours of July 11, 2021, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation was called to Durk’s home after several people broke in and exchanged gunfire with Durk and India, who were armed. The couple wasn’t hurt, and the intruders were never identified or caught.

Looking back, Dontay Sr. says Durk was hurting badly during this period. But while he grieved privately, he remained stoic publicly. “I don’t show emotion,” Durk would say in an interview. “You’ll never even see me shed a tear. … You gotta be careful how you tell people, what you tell people, because they can use it against you. They can find out your weaknesses.”

His music was his outlet for his pain and anger. That August, he announced on Twitter that he would stop dissing the dead in his songs. The living were another matter: Even if Durk wasn’t seeking revenge, his music led people to believe that he was. In October, Durk released an emotional track called “Pissed Me Off,” in which he mourns Dontay’s death and expresses a desire to get revenge. “I lost bro,” he raps. “I can’t be happy till we creep up on the score.”

Despite the persistent violent overtones of his music, Durk continued to move into the mainstream. He scored an unexpected cross-genre hit with “Broadway Girls,” a collaboration with country star Morgan Wallen that debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart after its release in late 2021.

Behind the scenes, court documents allege, Durk was working on more nefarious projects. On January 27, 24-year-old Stephon Mack was shot dead by two masked gunmen as he was exiting the Youth Peace Center of Roseland. The killing barely made the news at the time, but nearly two years later, the case would grab headlines when two men, Anthony “AJ” Montgomery-Wilson and Preston “Marley” Powell, were indicted by a federal grand jury in Chicago on charges that they killed Mack as part of a conspiracy to commit murder for hire.

According to the indictment and an FBI search warrant application filed in the case, Montgomery-Wilson is associated with Mike City, a Black Disciples faction with ties to OTF; Powell, the court filing said, lived for a time in the BD set’s territory. Mack, investigators believe, was a leader of the Gangster Disciples clique Smashville, and it was an associate of Mack’s who was suspected of killing Dontay Jr.

On February 10, two weeks after the murder, there was an exchange of text messages on Powell’s and Montgomery-Wilson’s phones in which payment for Mack’s murder appears to have been discussed, according to the search

warrant affidavit.

“Wassup with otf,” the text read, seemingly referring to Durk’s collective.

“Nothing,” replied a text from Montgomery-Wilson’s phone.

“Wym they not paying.”

“We waiting he comes up here on the 17th.”

On February 18, the user of Powell’s phone followed up: “Did durk gave u that money,” the message allegedly read.

During the probe, investigators allegedly confirmed that Durk had been in Chicago around the time discussed, filming the music video for “Ahhh Ha,” a single from his forthcoming album. Released on February 22, the track pays tribute to Von and takes shots at his rival NBA YoungBoy, though it never mentions him by name. “Don’t respond to shit with Von / I’m like, ‘Fuck it, you trippin’, go get your gun,’ ” he raps.

In his search warrant affidavit, the FBI agent working the case said some of the song’s lyrics “can be reasonably be interpreted to be a reference to Mack’s murder.” The document cites this verse: “We be slidin’ through they blocks and they don’t know we have / Buddy ass got shot and we ain’t claim it but I can show his ass.” In another verse, the affidavit points out, Durk may be alluding to having gotten revenge for Dontay’s homicide: “My brother DThang just got killed and I been slow since / But we got back on they ass, I bet they know this.”

While Durk prefaced the song with a disclaimer that the events described in the lyrics aren’t real (“just in case the police listenin’ ”), law enforcement took his words to be potentially true nonetheless. As further evidence supporting the search warrant, the FBI agent cited a Facebook story allegedly posted by Montgomery-Wilson roughly a week after the song dropped. The post features a picture of him fanning out a wad of bills overlaid with the verse from “Ahhh Ha” about “slidin’ through they blocks.” The song plays in the background.

In October 2022, as the FBI was quietly investigating Durk for possible involvement in Mack’s killing, the Fulton County district attorney’s office in Atlanta abruptly dismissed its 2019 case against Durk in the shooting of Alexander Weatherspoon. The office offered few details as to why, but Arora, Durk’s attorney, thinks it simply lacked sufficient evidence to get a conviction.

The dismissal ended a three-and-a-half-year saga that was, says Banks, “a wake-up call” for Durk, a scared-straight moment and a realization that he now had so much more to lose. Career and fortune aside, he had eight kids, including the youngest, Willow, his 3-year-old daughter with India Royale, and India’s older daughter, Skylar, from a previous relationship. “From that point on, everything was changing,” recalls Banks. Durk would eventually enter rehab, acknowledging in one interview that he’d been “letting the drugs take over me,” and start therapy.

He also increased his charitable efforts and community engagement. His Neighborhood Heroes Foundation handed out thousands of Thanksgiving turkey dinners in the Chicago area. In 2023, the foundation and its partners awarded $50,000 scholarships to two Chicago students for tuition at Howard University. By that year, records show, contributions to the charity would reach nearly $714,000. The same year, Durk donated $150,000 to Brandon Johnson’s mayoral campaign, making the rapper one of Johnson’s largest contributors, apart from labor unions. He sat courtside at a Chicago Sky game, next to Kim Foxx, the Cook County state’s attorney at the time.

But even as Durk was changing his image and making inroads with some of Chicago’s top leaders, the FBI was investigating him for another murder: the August 2022 attempted hit on Quando Rondo. Prosecutors say members of OTF learned that the Georgia-based rapper was staying at a hotel in Los Angeles and tracked him there. According to the indictment, Durk had allegedly offered to “pay a bounty,” including “lucrative music opportunities,” to anyone who killed him.

On August 18, according to the criminal complaint, Deandre Dontrell Wilson (known as DeDe), Keith Jones (Flacka), David Brian Lindsey (Browneyez), Asa Houston (Boogie), and an unidentified fifth person flew, allegedly on Durk’s orders, from Chicago to San Diego. Wilson and Houston are members of OTF, prosecutors say. Lindsey and Jones are members of other gangs in Chicago, and Wilson invited them to join the alleged plot.

Around the time that the airline tickets were booked, according to an FBI affidavit in support of the criminal complaint and arrest warrant, a text from a cellphone number believed to belong to Durk was sent to another associate. It read, “Don’t book no flights under no names involved wit me.”

Nonetheless, according to the affidavit, the tickets were paid for with an American Express credit card in the name of someone associated with OTF and were issued to an account belonging, in part, to Durk’s manager at the time, Ola Allibalogun. Another OTF member, Kavon London Grant, who goes by Vonnie, allegedly paid for a room for the men at the Sheraton Universal Hotel in Universal City, using an American Express card in Durk’s name.

Also on August 18, Grant and Durk flew by private jet from Miami to Los Angeles. After arriving, authorities say, Durk stayed at a rented house in Encino, taping a guest appearance on a podcast. (Investigators compared photographs of the home’s interior with footage from the podcast to establish that Durk was in town that day.)

Grant, meanwhile, met up with the five alleged hit men. Prosecutors say he supplied them with two cars — a rented white BMW sedan and a white Infiniti sedan with a fake license plate — as well as two guns, one a modified automatic machine gun. Grant also allegedly bought black ski masks from a sporting goods store.

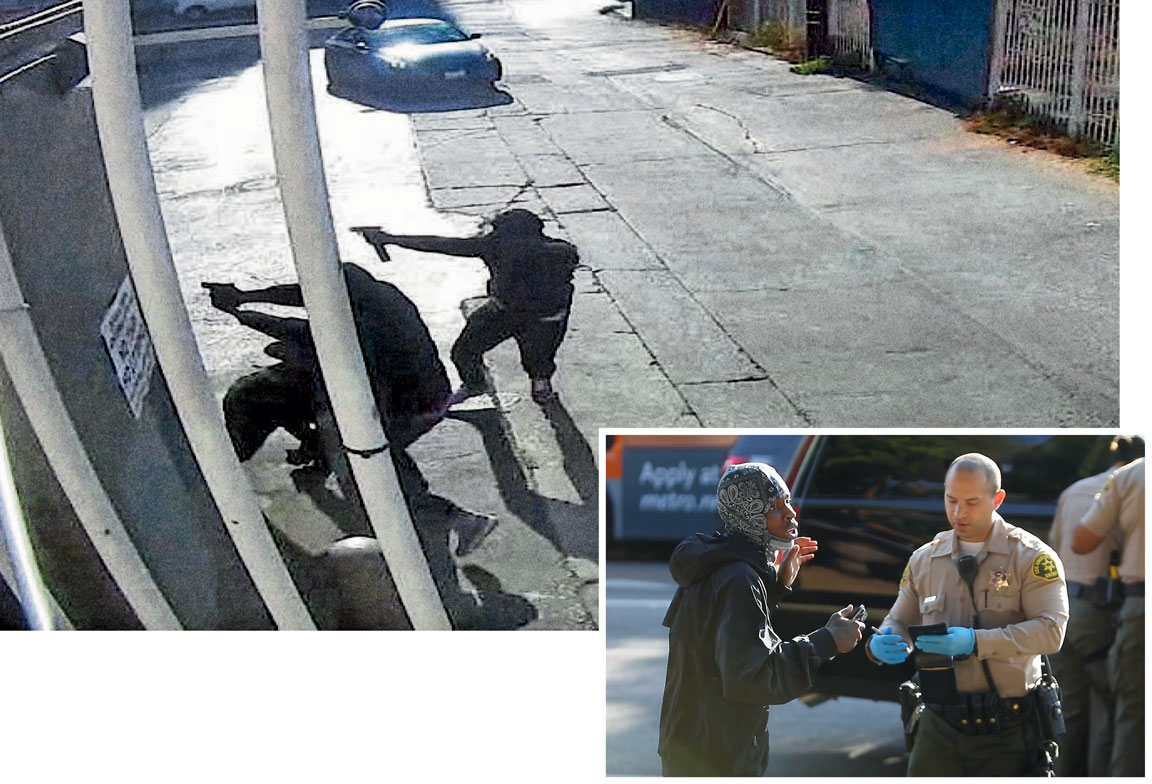

The next day, by the government’s account, the hit men, joined by Grant and driving in white cars, proceeded to “stalk” Quando Rondo, who was with his cousin, Saviay’a Robinson, tailing their black Escalade from their hotel to a marijuana dispensary and then a clothing store in West Hollywood. Various surveillance videos allegedly captured the Infiniti and BMW carrying the hit men as they followed Quando and Robinson around the city.

When the Escalade pulled into a gas station near the Beverly Center shopping complex, Houston allegedly parked the Infiniti in an alley. Prosecutors say Jones, Lindsey, and the unnamed accomplice — all wearing ski masks — got out and started shooting at the Escalade. Quando Rondo was inside the vehicle and wasn’t injured, but Robinson, standing outside, was killed in the hail of bullets. The shooters fired at least 18 rounds, by the FBI’s count, before hurrying back to the Infiniti and speeding off. (An FBI affidavit says the BMW had driven away just before the shooting.)

Video footage of the scene, aired on local TV news, shows a distraught Quando Rondo, dressed in black and wearing a camo balaclava, reeling in horror on the sidewalk by the shot-up Escalade, where Robinson lay. He clenches his stomach and wails in agony, “Nooooo!”

Shortly afterward, according to the FBI, the men were captured on surveillance video at an In-N-Out Burger in Los Angeles. Grant, Jones, and Wilson showed up in the BMW. Lindsey and the unnamed hit man arrived in a black SUV, not the Infiniti they were allegedly seen in earlier. Prosecutors claim they discussed their payment with Grant, and a few hours later, all the men, except for Grant, flew from San Diego back to Chicago, their tickets allegedly paid for using an OTF credit card.

Last October 17, a California grand jury indicted Grant, Wilson, Jones, Lindsey, and Houston on charges of conspiracy to commit murder for hire and other crimes. A week later, authorities rounded up the men in Chicago. The same day, FBI agents were alerted by U.S. Customs and Border Protection that Durk had booked one-way tickets on two international commercial flights leaving that night: one from Miami to Dubai and another from Fort Lauderdale to Dubai. Later that evening, the FBI received another notification that Durk was booked on a private jet, from Miami to Italy, scheduled to take off in just about two hours.

About an hour before that flight, authorities arrested Durk. His lawyers insist that he was not trying to flee. They say his intended final destination was Dubai, which, they contend, should not be viewed as unusual, given that Durk is Muslim. The United States does not have a formal extradition treaty with the United Arab Emirates.

When prosecutors initially brought charges against Durk later that month, an essential piece of their case — in addition to the phone and financial records and cooperating witness accounts — was the rapper’s own words. Authorities claimed he had bragged about the killing afterward in his music. They presented Durk’s lyrics from “Wonderful Wayne & Jackie Boy,” his collaboration with Babyface Ray, released in December 2022, three and a half months after the shooting.

The lyrics, prosecutors contended, seem to match the ambush like a play-by-play account: First, the tip-off to their location: “Told me they got an addy (go, go) / Got location (go, go).” Then the attack: “Green light (go, go, go, go, go).” And Quando’s anguished reaction: “Look on the news and see your son, you screamin’, ‘No, no’ (pussy).”

But Durk’s lawyers presented evidence — sworn affidavits from the producers who worked on the song — that Durk had recorded it in January 2022, seven months before the shooting. Prosecutors have since removed the lyrics from the indictment.

Durk has a heavyweight defense team in his corner: Atlanta’s Drew Findling, the so-called #BillionDollarLawyer who has represented Gucci Mane and other big-name rappers, and prominent Chicago litigator Jonathan Brayman, who has defended Durk over the years. But so far their efforts to get him out of jail have failed. Durk has been denied bail three times, including in June, when a judge cited the threat of witness intimidation, the possibility of Durk fleeing, and the danger his release would pose to the community.

When a different judge denied Durk bail in May, she noted that Durk had misused his phone privileges while in detention, citing a report that the rapper had used the phone accounts of at least 13 other inmates. “It shows a disrespect for the rules, and that is precisely the court’s concern,” the judge said.

After that hearing, Findling expressed his frustration and disappointment. The case against Durk “all comes down to one out-of-context text message,” he told reporters, referring to the text that Durk allegedly sent to an associate instructing him not to leave a paper trail when booking the airline tickets that might lead back to him.

It’s spring, some five months after Lil Durk’s arrest, and Dontay Banks Sr. is talking about the parallels between his own life and his son’s. He’s seated at a table in a converted warehouse on East 95th Street, down the road from Chicago State University. The building serves as a satellite location for Chicago CRED, the antiviolence program where he works, which was cofounded by Arne Duncan, a former Chicago Public Schools CEO and U.S. secretary of education.

Echoes of a counseling session in a nearby conference room filter in. As do the sounds of kids shooting hoops. Young men trickle in and out of the center.

Banks speaks in calm, measured tones, like a teacher. He talks candidly about his own trials and tribulations but politely declines to discuss the particulars of his son’s case. Leave that, he says, to the lawyers. (Lil Durk’s legal team declined to be interviewed while the case is pending.)

Even with the seriousness of the charges, Lil Durk’s legal plight hasn’t hurt his popularity. If anything, it has bolstered his cred.

To Banks, Lil Durk’s legal problems feel full circle. It “hurts real bad,” he says, that his son is now, like he had been, caught in the crosshairs of the federal government.

Banks was 24, with five young kids, when he was convicted of distributing crack cocaine. But selling dope was a life that was thrust upon him, he says. When he was a teenager in Englewood, his three older brothers were all incarcerated, and his mother, a single parent, struggled to provide for the family. One day, Banks came home from school to find the furniture on the front lawn. The family was being evicted. Needing money to support them, Banks turned to a cousin who dealt drugs. “Sometimes you have no other choice,” he says. “Sometimes you are led to that life even though you don’t want to go to that life.”

Under the mandatory minimum sentencing laws of the time, which were tougher on crimes involving crack, Banks was given life in prison without the possibility of parole. The federal government eventually addressed the racial disparities in these cases, and Banks was released after 26 years.

The way he sees it, the indictment against his son represents an insidious larger trend, one that comes down to race. Law enforcement, he says, is targeting Black men “to tear us down.” Just as he and others of his generation felt the brunt of the tough-on-drugs policies of the 1990s, he says, now the government is punishing their kids by criminalizing their creative expression and using laws intended to target criminal syndicates like the Mafia to go after rap collectives.

After getting the call about Lil Durk’s arrest, Banks went to Miami to see him. Ever since, he says, he’s been “hands on” with his son, “telling him every step what to do and how to fight this.” (Banks fought his own case while in prison, even writing motions and briefs by hand.) He talks to Durk or to his lawyers almost daily, and he has flown to Los Angeles several times to see his son in federal detention — a striking reversal of roles. He knows his son is facing a daunting fight: “Being in the feds ain’t no small task. They put you in a hopeless situation.” He is buoyed by the fact that his son has been converting fellow inmates to Islam.

He is encouraged, too, by the support Durk’s fans have expressed. Though Broadview rescinded the key to the village it awarded Durk days before his arrest, Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson hasn’t turned his back on the rapper, telling reporters that he refuses to pass judgment on a Black man before he’s tried. And Banks is thankful that Durk’s label, Alamo, has rallied to his defense, offering to contribute $1 million to secure his bail.

Even with the seriousness of the charges, Lil Durk’s legal plight hasn’t hurt his popularity. If anything, it has bolstered his cred. He released his ninth studio album, Deep Thoughts, in late March, while behind bars. “I wasn’t gon put this out but then I remembered the streets need this,” said a message posted on his behalf on social media. The album hit No. 3 on the Billboard 200. It’s a lesson Lil Durk learned long ago: Never miss a chance to turn controversy into opportunity.