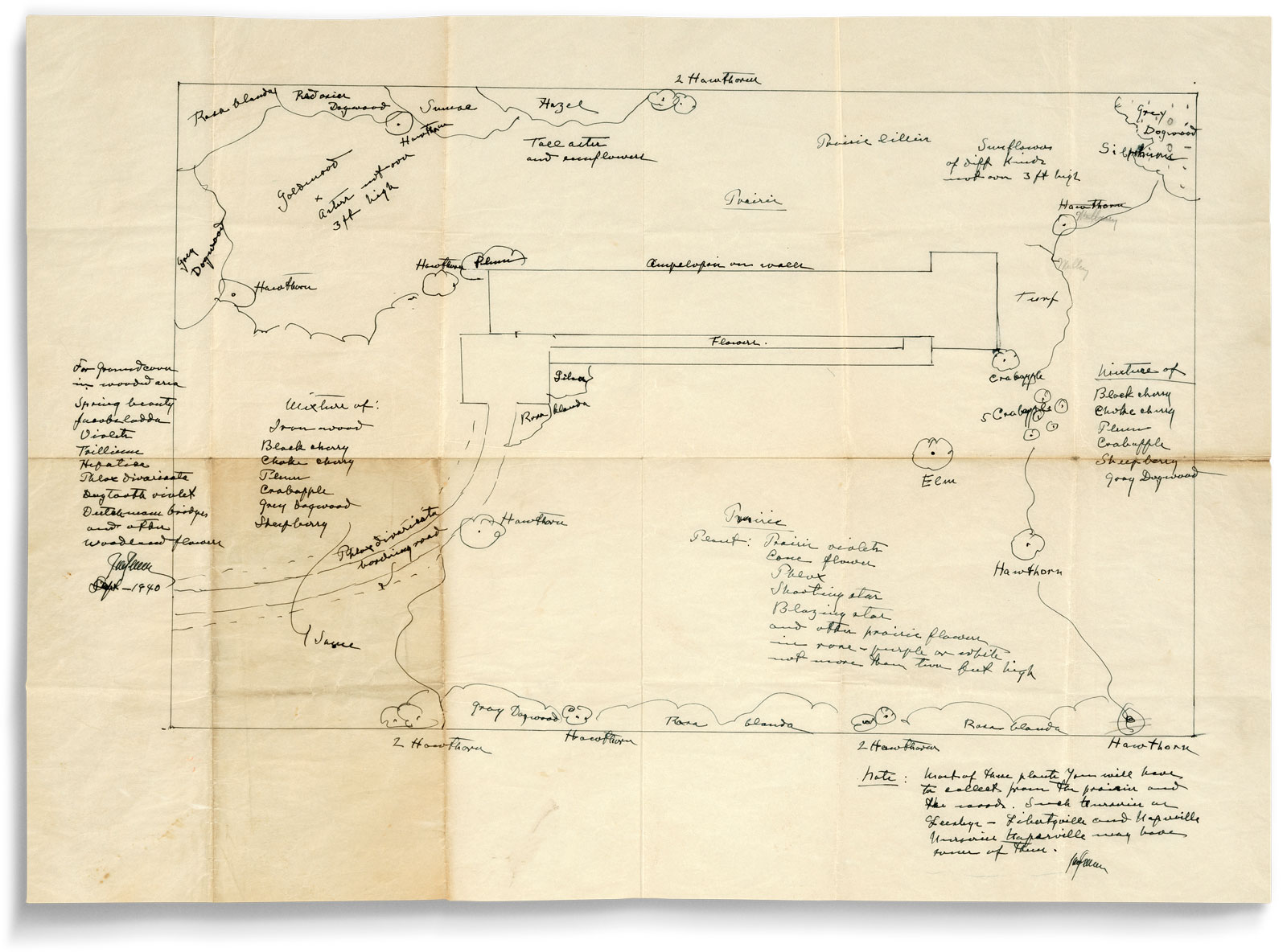

The lines extend with the occasional loop, embellishments that almost seem to bend and sway. The floating dot of an i sits next to a t whose cross arcs before it’s flicked to the next letter. Each capital I is a stately series of flourishes, while every m is a hurried afterthought that looks more like three straight lines than a series of mounds.

“Most of these plants you’ll have to collect from the prairies or the woods,” the note reads, followed by a list of towns where they could be found, including Libertyville and Naperville. The handwriting appears rushed, but elongated, as if there’s no patience for precision but room to let the words stretch. If the sentences ebb and flow across the page like a gentle breeze, then the writer’s signature at the end is a sharp gust: constricting letters, tall and narrow, that fall and crash against each other as a kind of punctuation. As if to make its implicit instruction an exclamation: Go to the prairie! Signed, Jens Jensen.

Phil Ponce also can’t make out much of the famous Chicago landscape architect’s handwriting. We’re sitting in his living room, with his wife, Ann, seated across from us in a high-back chair, a fire crackling in the fireplace. It’s a chilly early-May afternoon, and we’re trying to decipher the bit that comes after “Naperville.” Ponce laughs, flashing a smile recognizable from his long tenure as the host of WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.

Ponce is showing me a reproduction of a Jensen landscape sketch and instructions. There’s a list of plants (“A mixture of ironwood, black cherry, chokecherry, plum, crabapple, grey dogwood, sheep berry,” reads one note) and rapidly drawn swirls meant to represent trees and shrubs. What seems to be a path swoops up the middle of the page to a rectangle that Jensen has surrounded with lilacs and crabapple and plum trees. This part is easy to decipher: a driveway leading up to a house. The house that we’re currently sitting in.

In 2023, the Ponces, casually considering a downsize and a move from Ravenswood to be closer to their adult children in the north suburbs, were scrolling through Zillow listings with friends over Easter brunch. “This one looks interesting,” somebody said, holding up his phone to show a small but charming white cottage in Northbrook, long and narrow, with large windows. The guests hadn’t even left yet when Phil made an appointment to see the house the next day.

“I was furious. Furious!” Ann tells me. She shoots Phil a teasing glance. “Like, can’t you just give me a few days to catch my breath after hosting all these people?” She was still mad when they got to the house with their real estate agent, who was a friend. When she looked around, she told the agent, “You should buy this house.” But now, as a cardinal alights on the grass just outside the window behind her, Ann concedes: “What I was really saying was I should buy this house.”

Both Phil and Ann fell in love with it before knowing that the original owners were photographer Helen Balfour Morrison and her husband, Robert. They found that out after learning the house was being sold by the Morrison-Shearer Foundation, started by Morrison and her close artistic collaborator of over 40 years, dancer Sybil Shearer. The foundation had entertained a variety of offers from local developers, folks interested in splitting up the three-acre property or tearing down the house to make room for something more in line with the newer builds popping up around the neighborhood. The Ponces wrote a letter. Ann, herself a painter, promised to keep the creative spirit of the house alive, that it “would continue its history as a place where the visual arts are honored.”

It was enough to convince the foundation’s board, and soon the Ponces were closing on the house. They had negotiated to keep Helen’s books and some of the original furniture, but what they hadn’t expected, as they signed the paperwork, was for an original Jensen sketch of landscape plans for the property to be placed in their hands. Dated 1940, it was drawn the same year the house was completed.

“I was beside myself,” Phil says. “Oh my gosh, this little gem has landed in my hands. How do I take care of this baby so that it comes to life?”

What the Ponces learned, as they held the sketch and marveled at what they’d just inherited, was that Jensen’s plan had never been implemented. But calling it a plan, or even a vision, feels like an overstatement. And that’s part of the charm. There’s no scale, no scientific names for the plants, but instead circles around the perimeter, suggesting where gray dogwood and sumac and hazel trees should be planted, and smaller circles dotting the property, representing hawthorn and elm trees. There are ink spots, erased pencil. The word “prairie,” in Jensen’s elongated script, is crossed out in the middle, as if it had been misspelled and an attempt was made to correct it.

“Oh my gosh, this little gem has landed in my hands,” Phil Ponce says of Jensen’s sketch. “How do I take care of this baby so that it comes to life?”

I’ve asked the Ponces and a handful of Jensen experts what to make of it. There’s a collective agreement that this was not a formal plan but more of a suggestion, if anything. “My impression is that pretty frequently, Jensen would offer advice. Particularly when he was living in Highland Park,” says Bob Grese, a professor emeritus of environment and sustainability at the University of Michigan who has written extensively about Jensen. Grese says there are lots of stories about Jensen walking around and advising people on their landscapes. “One person shared that when they were children, they woke up to their parents frantically digging up these plants in the front yard that they had just planted. And it was because this man named Jensen had come by and told them that they made a serious mistake.”

As the superintendent of Chicago’s West Park System, Jensen had made a reputation for himself, designing iconic spaces like the Garfield Park Conservatory, Humboldt Park, and Columbus Park using native Illinois plants, which other landscape designers dismissed as weeds. Born in Denmark, Jensen immigrated to the United States in 1883, arriving in Chicago by way of Florida and Iowa. He was particularly drawn to the plants he discovered in the Midwest — the poetry of the deciduous forest and the friendliness of the plains . At a time when most landscapes were filled with exotic plants that struggled in the Chicago climate and required considerable maintenance, Jensen looked instead to plants, like purple phlox and fiery goldenrod, that thrived here. “To me,” he wrote in his 1939 memoir, Siftings, “no plant is more refined than that which belongs.”

In his plan for the Morrisons, he dots the landscape with native shrubs and trees. A hawthorn (which he calls “always illuminating” in Siftings) is placed at the curve of the driveway. A crabapple (“its lavender touch reflected on massive snow fields, turning into a delicate blue in the light of the day’s afterglow”) stands at the southeastern end of the house. There’s witch hazel (“like a golden mist driving through our woodlands”) behind the house, and phlox (which “make a garden full of song”) in front. This sketch, though casual, reads more like poetry than an offhand suggestion. There’s also a friendly familiarity in the precision of the driveway’s arch, the approximation of the size of the house — one that comes from knowing it well, through lingering conversations across from a crackling fire, like the one I’m having with the Ponces. As we talk, Ann brings over one of Morrison’s books from the bookshelf, a first edition of Siftings. Inside is an inscription: “To my friend Helen Morrison who has vision and a real interest in her fellow man. Jens Jensen.”