I listen to a lot of podcasts. When my life is extremely stressful, which it is right now, I listen almost exclusively to baseball podcasts, the more nerd-driven, statistically oriented the better. They have all the escapism of sports minus the screamo tantrums of drive-time talk. I also read a lot, and when the news is extremely stressful, I do the same.

Then the Aroldis Chapman trade happened, and real life intruded on my best release valve. The Cubs dealt for Chapman, a closer who was suspended earlier this season for allegedly choking his girlfriend and firing a gun at her. He later faced criticism for deflecting blame about the incident.

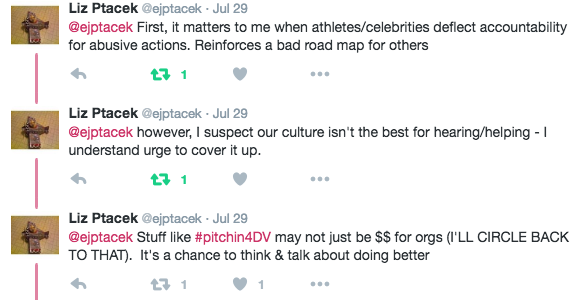

Journalist Caitlin Swieca decided that she would donate $10 for every Chapman save to a domestic-violence charity; Julie DiCaro, whom I interviewed about the More Than Mean PSA about online harassment a while back, suggested the Domestic Violence Legal Clinic, where my wife works as an attorney. All of a sudden, prominent figures in baseball Twitter, like ESPN's Jonah Keri, were name-checking my wife's employer and donations were flooding in. As of the 30th they'd received over $1,000 in donations, and they're not the only recipient of the @pitchin4DV effort.

I got to sit and watch it happen, live, sitting on my couch. My wife tweeted a few things in response.

This captures a lot of what I heard when baseball writers were forced to grapple with the Chapman trade. Or maybe forced to is the wrong word; they acknowledged Chapman's actions and their ramifications on the game, despite not really knowing what to say, or what baseball/the Cubs should do about the abuse itself. Still, this is a good thing—talking about it—even if what we're talking about is not knowing.

And there are understandable reasons for the confusion, as Meg Rowley wrote in Baseball Prospectus, after Jose Reyes—another abuser who recently made his return to baseball for a contending team—was arrested:

That process can nevertheless be uncomfortable; sometimes you just want to drink a beer and watch a game. It isn’t particularly fun to experience sports that way. It’s why we chafe at those moments when we can see the seams, when labor disputes or racially charged commentary abrade the shine of a well-struck home run and reveal the social constructs beneath it. For much of the game's history, our reaction to domestic violence was conditioned by the societal acceptance of it. This was how conflict was resolved, how power at home was asserted and replicated, and discussing it in public was untoward. We’ve arrived at a painfully fought cultural disdain for domestic violence, and now the seams of the game are being pried open, with the failures of the past peeking through to confront the possible failures of the future.

Domestic violence was only really codified in the 1970s; America's first battered women's shelter (the first name the new concept took) didn't open until 1973. Chicago got its first in 1976, the work of Susan Schechter, a graduate of UIC's Jane Addams College of Social Work, who would become a leader in the study of domestic violence. When Schechter spoke about her work for the pioneering Chicago Abused Women's Coalition, "professionals grappling with the information" blamed the abuse on "women's personalities." It was even given a term, "women's masochism," which persisted as an explanation for years:

The most ''tragic irony,'' Dr. Caplan said, is that many women trying to avoid pain ''are accused of wanting pain for masochistic reasons.'' She added: ''The most awful instance of that is battered wives.''

She explained that women who stay with abusive husbands have been accused of masochistic behavior, although they may instead be afraid of the violent consequences of leaving. ''Some of these women are so vulnerable that they are bonded not to the abuse, but to the occasional affection these men express,'' Dr. Caplan said.

Activists like Schechter persisted, and their work in the 1970s and 1980s seemed to bear fruit in the 1990s and 2000s. Rates of domestic violence fell precipitously, and the evidence suggests that the massive expansion in services and resources for abuse victims—the kind of work that @pitchin4DV benefits—is the main reason.

But that still leaves the men who abuse women. And no one really knows what to do about that: "the technical social science term for this is: Oy," a sociologist told NBC News in the wake of Ray Rice's abuse.

Around the same time, ESPN's Sarah Spain, who collaborated with DiCaro on the More Than Mean video, spoke with a couple experts who painted a complex portrait of how we should respond to domestic violence in athletics, which in turn reminded me of what my wife said about how "our culture isn't the best for hearing/helping."

Said Linehan: "What's needed is a bigger emphasis on redemption, which is a bigger emphasis on teaching skills. If you teach skills to a person who wants to change, you can definitely help them."

Goodmark and Linehan said the best way for the NFL to tackle its domestic violence problem is from the inside out, using the power of its own community.

[snip]

"The research shows that male peer-to-peer intervention is more effective than almost anything else in getting people to change their abusive behavior," Goodmark said. "So imagine if you could cultivate within a group of guys whose mission it was to ensure that they weren't going to have these kinds of problems on their team."

It's a discomfiting notion. Even having written about the potential pitfalls of a zero-tolerance policy on domestic violence, Spain, a Cubs fan, wrote that she "dreaded the [Chapman] deal going through," not least because of how Chapman undermined the incident's gravity even after his suspension was done. At The Athletic, Lauren Comitor writes that she "didn't really believe the Cubs would pull the trigger on a player suspended for domestic violence," but despite her reservations, she won't stop watching the Cubs.

It might seem contradictory, but we just don't know what to do with someone like Chapman. We don't know for sure whether it's better for him to remain in organized baseball—or, even if it is better for him and his family, whether it "perpetuate[s] a sports culture that normalizes domestic violence," to quote Comitor. We're the first generation to grow up with the idea of domestic violence. Whether we cast out abusers or not, we do so with the heavy realization that it could be the wrong decision. The only thing we know that works is what #pitchin4DV is doing—helping the victims that need it.