When Mark Sorensen moved from Chicago to Decatur in 1969 to teach in the public schools, and later at Millikin University, he heard locals claim that his new hometown was the birthplace of the Chicago Bears. Years later, when he was named Macon County historian, he decided to check that rumor out.

“I certainly wasn’t aware of it when I was growing up in Chicago,” Sorensen said.

The Bears have rarely made much of the two years they spent in Decatur – the first as a factory team owned by the A.E. Staley company, a starch manufacturer, and the second as a charter member of the American Professional Football Association, the precursor to the NFL.

But as the Bears prepare to commemorate their 100th season, the team held a “Return to Decatur” event in its hometown last month. The team donated money to youth football programs, held a training camp with former players Alex Brown and Jason McKie, and brought coach Matt Nagy down for a press conference. More than 1,000 fans — some wearing vintage-looking "Decatur Staleys" t-shirts — bought tickets to a panel discussion on Bears history. Chairman George McCaskey, grandson of longtime coach George Halas, told them exactly what they wanted to hear.

“Without Mr. Staley’s vision and his entrepreneurial spirit, the Bears would not be here,” McCaskey said. “So we are very grateful to have had our start in this great town — and it’s great to be back to celebrate our centennial right here in Decatur.”

In early 1920, George Halas was an ex–University of Illinois football player and major-league baseball washout, having hit .091 the year before in 12 games as a right fielder for the Yankees. New York found a better right fielder, and Halas needed a new job. A.E. Staley Sr. asked Halas to come down to Decatur and coach the company team, which he hoped would improve employee morale and generate buzz for his corn starch.

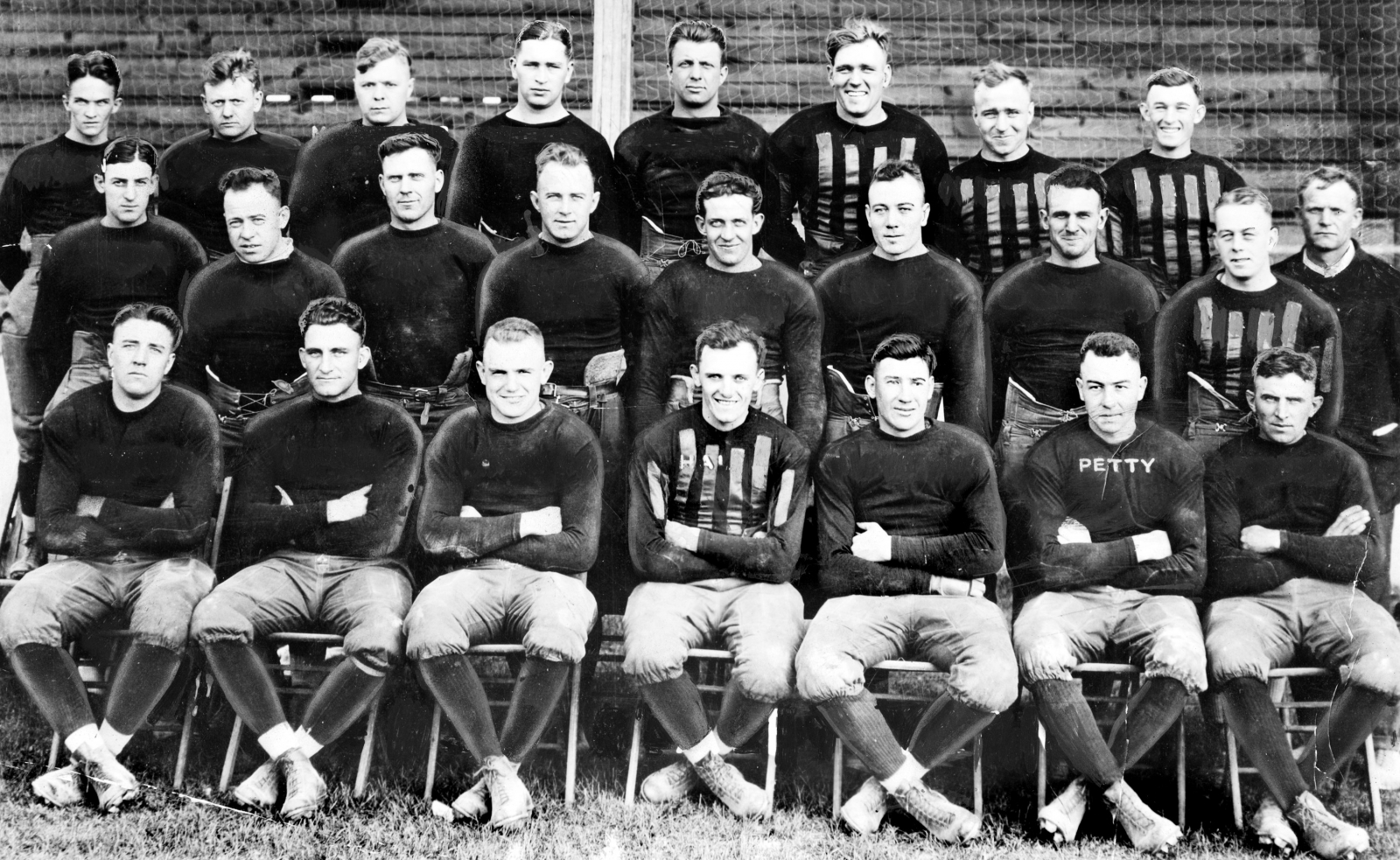

The NFL has its roots in small industrial towns of the Midwest. The Decatur Staleys, as the team was called, started with an exhibition game against the Moline Universal Tractors on October 3, 1920, and played their first league game on October 17 against the Rock Island Independents.

Sorensen dug into the Bears' origins in Decatur for an article titled "Corn Hustlers: How Decatur Starchworkers Became Chicago Bears." Here's his account of that first official game:

"A special train was chartered and 200 Decatur boosters joined fans from around the state to see the favored Independents. Halas and the other ten starters played the entire game on both sides of the ball with no substitutions. The Staley Fellowship Journal reported, 'Without doubt the greatest achievement in the history of Staley athletics occurred Sunday, October 17, when George Halas and his wonderful starchworker eleven humbled the famed Rock Island Independents, to a tune of 7 to 0, before 5,000 fans in the Island city.' "

The Staleys went 10-1-2, finishing second to the undefeated Akron Pros. (The Staleys are one of two surviving teams from that season. The other is the Chicago Cardinals, now in Arizona. They're the league’s oldest franchise, which began as a local club team called the Racine Street Cardinals in 1898.)

Football didn’t turn out to be the profitable investment Mr. Staley had hoped. It also failed to improve morale. Workers in his starch plant resented Halas and the players, who held part-time jobs which allowed them to practice and travel to games. The team lost $14,000 of the company’s money. Attendance in Decatur never topped 4,000 fans.

But when the Staleys met the Cardinals in Cubs Park on December 5, 1920, 11,000 fans showed up. So the next season, in 1921, the Staleys played their first two games in Decatur, then moved to Chicago. Mr. Staley didn't just encourage the move — he gave Halas $5,000 to leave. The only string was that the team had to be called the "Staleys" for the rest of the season.

“George, I know you like football more than starch,” Staley told Halas, according to the biography Papa Bear: The Life and Legacy of George Halas, by Jeff Davis. “Why don’t you take the team to Chicago? I think football will go over big there.”

And thus Staley got rid of a red-ink line on his ledger that is now worth $2.45 billion to Halas’s heirs. In 1956, Halas showed his gratitude by holding a “Staley Day” at Wrigley Field for the company’s 50th anniversary. The University of Illinois marching band spelled out “S-T-A-L-E-Y” on the field, and fans received souvenir tie clips adorned with a football reading “Staley Bears, 1920–22.”

The Bears made an attempt to reconnect with Decatur in 2002, the first of two seasons the team played at the University of Illinois’s Memorial Stadium while Soldier Field was under renovation. The team planned to bunk in Decatur on Saturday nights and commute to Champaign on Sundays. Decatur was so excited it put up welcome signs declaring itself “The Original Home of the Chicago Bears.”

According to Sports Illustrated, though, “The plan was scuttled after the first preseason game, when the team bus got stuck in traffic going to the stadium. ‘It took us over an hour,’ cornerback R.W. McQuarters said. ‘Guys were sleeping on the bus.’ Perhaps still in hibernation, the Bears lost 27-3 to the Broncos.”

That felt like a kick in the teeth to Decatur. The city had just been through a rough decade which included three labor disputes, two tornadoes, and a controversy over the expulsion of six black students from an area high school, which brought Jesse Jackson to town to lead demonstrations. (The New Yorker even published a feature about why Decatur was living under such a dark cloud.)

The Bears made things up to Decatur a little in 2003, when they introduced a mascot named Staley Da Bear. That would be the fellow who dropped to his knees after Cody Parkey's game-losing double-doink in the playoffs last season.

Staley Da Bear died tonight, and Cody Parkey killed him pic.twitter.com/Cfzf80dGiu

— Deadspin (@Deadspin) January 7, 2019

Decatur’s baseball loyalties are divided between the Cubs and the Cardinals, but in football, it’s a Bears town all the way, Sorensen said. The Staley Museum, which opened in 2016, has a room devoted to the city's most famous creation. Nearly a century after they left, the Bears are finally returning some of that loyalty.