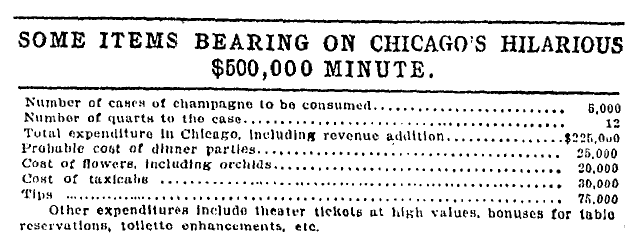

In 1909, the Tribune, in an early example of data-driven explainer journalism, took it upon themselves to calculate the cost of 12:01 on New Year's Eve: "Chicago's Hilarious $500,000 Minute."

In 2013 dollars, that's $12,773,720, including some $5,748,170 on 60,000 quarts of champagne. By my calculations (six ounces per glass, five glasses per quart), that's 300,000 glasses of champagne.

But it wasn't to last. 1909 was a turning point. 11 years before Prohibition, the city began cracking down on New Year's Eve, prodded and pushed into it by reformers.

It happened rather quickly. In 1905 and 1906, the perceived problem wasn't orgies of demon rum, but noise. On December 28, 1905, Chicago's police chief, John Collins, issued a prohibition on "excessive whistling": the "loud and prolonged noise made by factory, locomotive, and other whistles to usher in the new year." "Fifteen minutes is long enough," his order read. "When this time is exceeded stringent measures may be taken to stop the whistling."

Apparently it didn't work. The next year, the Tribune inveighed against the nuisance:

There is little doubt, however, that more persons sit up to watch the old year out than was the custom formerly. Many of them meet within the loop district with the avowed purpose of having what they call a "big time." For them the noisier the revelry, the greater the enjoyment.

Then something happened. This is from January 2, 1908, when two women were seen not merely smoking, but one was pouring wine down a plutocratic escort's back.

So went the account of President E.J. Davis of the Englewood Protective Association, a volunteer investigator of the Law and Order League. "In one of the tidal waves of hilarity a beautiful woman of matronly age took a sizzling bottle of champagne in her hands and poured it upon the bared head of her most favored escort, an elderly and portly, plutocratic-looking individual, announcing to all in the gilded drinking room that she was pouring a libation to the god Cupid."

The Law and Order League was an old organization, formed out of the wake of the Haymarket Riot, when it was observed that "a large proportion of the rioters were half-drunken boys." But buoyed by the rising tide of drys, the league and its fellow-travelers in the Anti-Saloon Campaign somehow managed to change the Establishment tone on New Year's revelry.

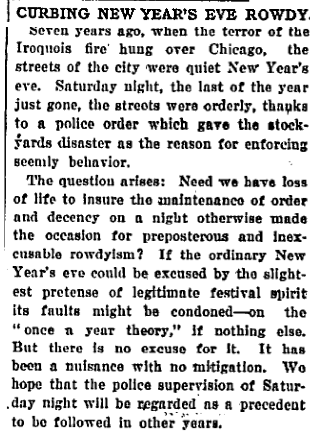

In 1911, the Tribune, which a few years earlier was merely exercised by the blowing of whistles, expressed relief that two immense tragedies—the Iroquois Fire on December 30, 1904 and the Stockyards fire of December 22-23, 1910—had calmed the spectacle of New Year's Eve:

On New Year's Eve, the paper published a call from the Young People's Civic League to call in the national guard if saloons weren't closed by 1 a.m.

The next year, 500 pastors planned a march on City Hall to protest the "3 o'clock" rule, which permitted establishments to remain open until 3 a.m., provided the doors were locked, no more patrons were admitted, and no drinks were sold after 1 a.m. This, the pastors predicted, would "literally turn the whole city into a civic First Ward ball"—a reference to the notorious political fundraisers hosted by the vice-district First Ward political machine.

A full moral panic took hold. In 1916, the Tribune editorial board was already on the case in mid-November, warning against "The Demon Rum and New Year's Eve": a "boor bacchanal, a booze carnival, the object of which is not to be happy but drunk," a "false carnival of the violent minority." (Eerily, they did defend liquor "upon the theory that people's moods and aspirations are too complex for the dead level of uncolored existence.")

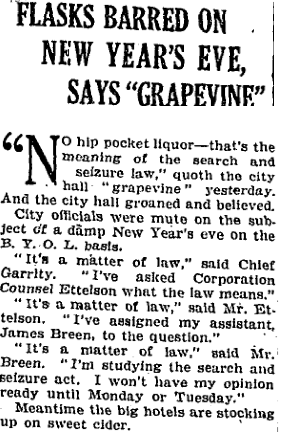

And it worked. In 1916, Mayor Thompson strictly enforced the 1 o'clock closing ordinance. In 1917, the city filed at least 22 suits against restaurant and cafe owners for staying open past 1 a.m. And a couple weeks before the nation went dry in the beginning of 1920, the city announced it was exorcising all traces of the demon:

Some of this can be attributed to the general progress of the Prohibition movement. But it's hard not to see it in the light of the First Ward Ball, which was held a couple weeks before New Year's and put the latter to shame (while raising tens of thousands of dollars for the ward machine):

The 1907 First Ward Ball was perhaps the most widely reported and for this reason, seemed to raise the most ire among the various reform movements in the city. By the time, the ball opened that year, there were 20,000 people jammed into the Coliseum. One reporter counted two bands, 200 waiters and 100 policemen at the ball and estimated that 20,000 guests drank 10,000 quarts of champagne and 35,000 quarts of beer.

One newspaper reported that there were so many drunks inside that when one would pass out, they could not even fall to the floor. In addition, women who fainted were passed over the heads of the crowd to the exits. As the event opened, a procession of Levee prostitutes marched into the building, led by Bathhouse John, with a lavender cravat and a red sash across his chest. Authors Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan described the parade: “On they came, madams, strumpets, airily clad jockeys, harlequins, Diana’s, page boys, female impersonators, tramps, pan handlers, card sharps, mountebanks, pimps, owners of dives and resorts, young bloods and ‘older men careless of their reputations’…”

1908 was worse, with some 10,000 quarts of champagne consumed—one-sixth of the whole city's total, if you go by the Trib's 1909 estimate. And they pulled it off even though the Coliseum had been bombed shortly before the party.

It was to be the last one. "A few weeks later the Chicago vice commission presented its report on the affair," Herman Wendt wrote. "The United States post office department for some time refused to let the document travel thru the mails, so shocking were the details." As preparations for the 1909 ball began, the city pushed back; tickets were already in hand when it was reported the mayor would shut it down.

The Levee's notorious alderman, John J. Coughlin, blinked, making the announcement in a poem: "No ball, / That's all." In its place, they held a concert with a military band from 8 p.m. to midnight.

Within a few years, the Levee would be shut down and the vice district pushed farther out from downtown and out to the suburbs. The alliance of reformers and teetotalers claimed victory, and the crusade transferred from the First Ward Ball to its civic equivalent.