My colleague Bryan Smith has a long, compelling piece on the south-suburban municipality of Robbins. I've been fascinated by the town for awhile, aware of its considerable problems and Cook County sherriff Tom Dart's focus on them. But I didn't know that I became interested in it for the same reason as Dart:

It was partly a quirk of geography that landed Robbins on Dart’s radar. A longtime resident of nearby Mount Greenwood, the sheriff would often pile the family in the car and drive down Kedzie Avenue, up and over the Cal-Sag Channel, along the spine of Robbins, to the movies in Crestwood. He would wonder how a place so close to Chicago could seem like such a backwater.

[snip]

When I ask Dart to explain why he’s made fixing Robbins his latest mission, he says he would rather show me instead. We meet in the shadow of the Robbins water tower, in the parking lot of the town’s sole gas station—a Citgo—and head down 135th Street in Dart’s black SUV. For Dart, it started here with a pair of houses he would pass on his drives through town. “Right there,” he says, pointing to one of them. The white siding of the two-story house gleams in the sunlight. Autumn has robbed the rows of flowerpots of their colorful blooms, but they neatly line a driveway that cuts into the well-trimmed postage-stamp yard. The other house, so close it almost elbows the first, rears out of a litter-cluttered dump—a charred husk, black as rotted teeth, with windows either shuttered with plywood or gaping open.

I drive through Robbins about once a month; I have family in the suburbs just to the west. We head east from Orland Park, its stages of development visible in the transition from the occasional old farmhouse to mid-century, one-story ranch houses to late-20th century subdivisions. Then through Midlothian and its comparatively dense, compact middle-class housing.

And then Robbins. As Dart observes, its problems (but also its residents' devotion to it) are apparent from the street. But it's also beautiful. It looks Southern; it looks like home, or at least not far from it (I grew up in Virginia).

As an example, here's a view of 135th Place in Robbins.

Or along Lawndale:

It's the little details that look familar: the mailbox on a weather-beaten post by a gravel strip worn out by cars from the lawn; the narrow road rolling down to the grass; the tidy lawn giving way to forest succession and the remnants of a modest old house. There are parts of Robbins that look more Chicago-suburban, because they came later, like the Golden Acres subdivision. But much of the small municipality looks like this.

Compare that to Midlothian, which is right next door.

Or Blue Island, just northeast.

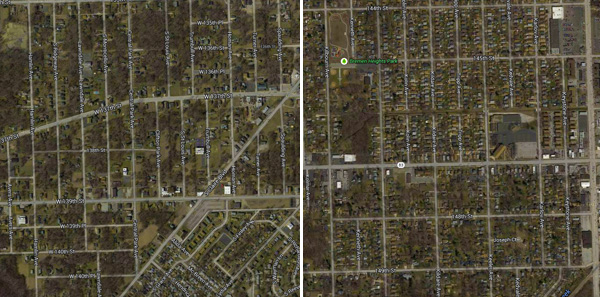

Robbins even looks different from space. On the left is Robbins (the newer subdivision is in the bottom right-hand corner). Midlothian is on the right. Robbins is not just covered in trees; there's no particular pattern to them.

They're not landscaped; they are the landscape.

Andrew Weise calls Robbins an "unplanned suburb." Thomas J. Kellar, Robbins's first president and the man who convinced the residents of the "Blue Island Settlement" to incorporate, describes how it was originally bought up in a land grab timed for the Columbian Exposition, but the city never made it that far, and the speculators were wiped out. Then the village's namesake, "Henry E. Robbins, seeing the possibility of helping colored people, induced a few to settle here on the abandoned lots, which he sold as cheap as $90 on the monthly payment plan."

Robbins's cheap land, combined with growing racial tensions in the city, made it an appealing destination for recent arrivals and migrants coming north on the Rock Island line. A Works Progress Administration text from 1933 describes the early residents of the town:

Whence came the Robbins Negro? Well, many of them are naturally from Chicago's teeming south side. They were motivated by the same objectives that prompt the white apartment dweller to throw his accumulated rent receipts into the landlords face as a final gesture of defiance and release, and [hie?] himself to a little home in the suburbs. A humble dwelling with a small plot of ground to raise corn, carnations, cabbages, and carrots; a few chickens; a luscious goose or two; and perhaps a shoat to fatten for next winter's larder. This is the perennial dream of the insipient surburbanite. But the Chicago suburban developments were restricted, and Negros more rigidly barred. Then, in 1917, Eugene S. Robbins [the son of Henry] subdivided this area and incorporated it for the express purpose of providing a Chicago suburban village for the colored people. The Negros of Chicago were not slow to grasp the opportunity. Some of then were workers skilled in the building trades, there was an ex-Pullman porter or two, many common laborers, a few college graduates, and a sprinkling of share croppers and plantation hands fresh from the south. Some purchased modest dwellings hastily erected by the real estate firm, while many could only muster the down payment for a lot. As there were no building restrictions these latter suburban aspirants haphazardly gathered a quantity of second-hand lumbers (perhaps some old car siding) some sheet tin, same cheap roofing paper, and assembled what was merely intended to be a temporary abode. Later, when they worked and saved a little money, they would build “real” homes. Certainly it was not their fault that these fond hopes were but infrequently consummated.

As Steven Reich writes of Robbins and similar suburbs in The Great Black Migration, "where there was vacant land, they worked to buy it and build homes. Consequently, they were more likely than city dwellers to be home owners—in many suburbs, a majority of blacks owned their homes. Even in the most congested suburbs, they grew gardens, kept small livestock, and used domestic space for income…. Households relied on extended families for economic as well as emotional support, and many explicitly rejected city living, preferring rustic landscapes reminiscent of the South."

The famous Pembroke Rodeo in Kankakee, founded by black rodeo rider Thryl Latting, actually has its roots in Robbins, where Latting grew up and received his first horse. His son Michael, who operates Latting Rodeo, went to Casper Junior College in Wyoming on a rodeo scholarship.

Robbins's quasi-frontier heritage was evident in 1922, when The Negro in Chicago, the famous study of the 1919 Chicago race riot, was published. The town had barely been incorporated when its authors captured a still-resonant portrait of Robbins, where "about 400 hard-working Negroes occupying seventy houses are trying to develop a town against the handicaps of lack of capital, swampy lands, and inaccessibility":

Robbins is not attractive physically. It is not on a car line and there is no pretense of paved streets, or even sidewalks. The houses are homemade, in most cases by labor mornings, nights, and holidays, after or before the day's wage-earning. Tar paper, roofing paper, homemade tiles, hardly seem sufficient to shut out the weather; older houses, complete with windows, doors, porches, fences, and gardens, indicate that some day these shelters will become real houses. In 1920 the village took out its incorporation papers, and while there are some who regret this independence and talk of asking Blue Island to annex it, in the main the citizens are proud of their village and certain of its future.

Infrastructure and housing remains a problem in Robbins to this day. But it inspired pride of place then as now: "men and women together are living as pioneer families lived—working and sacrificing to feel the independence of owning a bit of ground and their own house."

The appeal of Robbins grew organically out of its failure as a planned suburb, and its semi-rural, small-scale agricultural nature became part of the pitch, even as more traditional developments began to neighbor the settlers' homes as the the Great Migration swelled a segregated Chicagoland.

"A 1946 campaign for 'homesites' in the Lincoln Manor subdivision," Weise writes, "depicted children playing in the front yard of a new home while a woman sat on the front steps…. Blending elements of old and new, the ad portrayed a square-brick-faced bungalow typical of Chicago's southwest suburbs, plus a large garden plot—tilled for row crops, no less—at the back of the lot." Robbins grew slowly—431 residents in 1920, 1,300 in 1940, 4,766 in 1950—and it changed slowly as well, maintaining its semirural nature as it grew.

The comparatively undeveloped nature of Robbins was also its curse. As early as the WPA report, it was noted that "the total volume of business is low, for the chain stores in Midlothian and Blue Island got most of the grocery trade." Almost 70 years later, a transit-oriented-development study for Robbins concluded that "Robbins does not compete favorably with these clusters."

In 1949, the Tribune reported that half the homes in Robbins, many of which had been built on empty lots by the homeowners, had no running water, and that "73 percent of the dwellings in 1940 were 'in major need of repairs,' and only one area of the village, comprising a new subdivision, now has a sanitary sewer system. Problem No. 1 for improvement of the village, however, is the elimination of surface water." In 1971, the Trib reported that Robbins had "only four paved streets with curbing"; the rest was "macademized, a mixture of tar and gravel," a familiar aspect of the rural suburban landscape.

Visually, Robbins both subtly and unsubtly reflects this lack of infrastructure; when the town paved its streets and put in a sewer, it incurred substantial debts just before the deindustrialization of the south suburbs began.

As Smith's piece for Chicago makes clear, Robbins's physical infrastructure is mirrored by its civic infrastructure: "According to Dart’s office, the staff at that time consisted of only one full-time officer—the chief—and a collection of poorly trained part-timers. Their reports, Cara Smith says, were so lacking in basic information that they were essentially useless to a prosecutor."

But Smith's piece also details the small town's extraordinary history: the second black-governed community in the North, home of the first black-owned airport, home of several of the Tuskegee airmen. And that's mirrored in the landscape as well—a singular town, that looks like nothing else in Chicagoland.