In today's big political news, Illinois GOP legislators want the state to have fiscal control over Chicago Public Schools (which has happened before) and for CPS to declare bankruptcy.

It is not especially likely. The governor's all for it, but the GOP has to peel off enough downstate and suburban Democrats to pass it, and House Speaker Michael Madigan has already cast the specter of Flint's water crisis as an example of what can go wrong with a takeover.

The comparison to Flint (here's a good piece, written by a friend and Flint native, on what a disaster that city's emergency fiscal management has been) is extreme, but there's some actual precedent for it. In 1979, CPS went all but bankrupt—it can't actually declare bankruptcy, but the GOP's new proposal would allow it to do so—and fell under the control of the Chicago School Finance Authority.

CPS eventually righted its fiscal state, but as I've written before, after a decade of state fiscal control, school infrastructure problems had reached a crisis state. When Richard M. Daley regained control in 1995, CPS used its then-strong bond ratings to borrow money for capital improvements intended to stem the bleeding of students to the suburbs.

One reason students were bailing was the general instability. As noted in this compelling piece by WBEZ’s Becky Vevea:

There are few reasons to argue that CPS was at its best in the ’80s, because (among other reasons), CPS ran into financial troubles throughout the decade. Also, between 1979 to 1987, Chicago teachers went on strike nine times. Districts started measuring achievement and looking at dropout rates, and in Chicago, things did not look great.

In 1987, then-U.S. Secretary of Education William Bennett famously characterized Chicago schools as “the worst” in the nation. More than half of all students were dropping out of high school at the same time the value of a high school degree was increasing.

The headline is "Were Chicago Public Schools Ever Good?" "Good" is a relative term, but Vevea makes the case that they're better now than they've ever been.

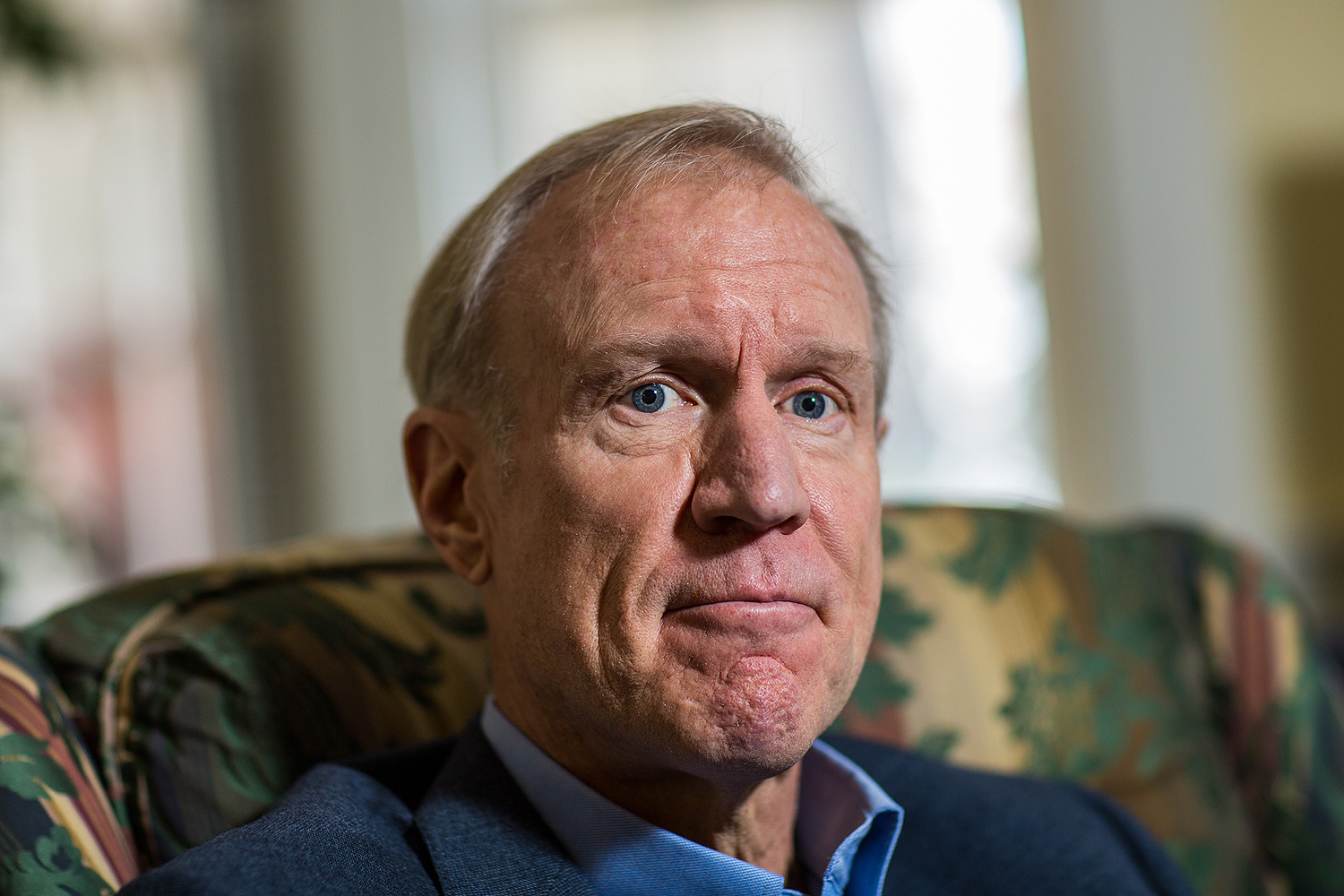

And a lot of people are wary about bankruptcy as a solution. Way back in April of last year—this is how long Governor Bruce Rauner has been pushing the idea—Greg Hinz of Crain's got dire warnings about the idea from Civic Federation president Laurence Msall, former Illinois Finance Authority chair Bill Brandt, and even Fitch Ratings. Hinz writes:

Private companies … usually can fire their entire workforce with relatively minor harm to the larger society. [I]nstitutions such as schools … can't just drop math instruction this year because it's unprofitable.

For reasons like that, veteran Chicago bond lawyer James Spiotto suggested in recent state House testimony, government bankruptcy is rare—fewer than 700 cases nationwide since the Depression, only six involving schools. “Chapter 9 is not a solution to the problems of a financially troubled (government). Rather, Chapter 9 is a process” to bring about compromise, he testified.

That's what Kristi L. Bowman, a law professor at Michigan State University, has found, and it's why she dismisses it as a solution in her article "Before School Districts Go Broke: A Proposal for Federal Reform":

In the long term, adjustments to CBAs [collective bargaining agreements] and debt obligations often, but not always, place the district on more advantageous fiscal footing. Although bankruptcy courts have the authority to unilaterally modify CBAs and to oversee the renegotiation of municipal debt, they are especially reluctant to do the former. Thus, unions and creditors sometimes attempt to renegotiate their contracts without the involvement of the court in an attempt to secure more advantageous terms.

Pensions compound the issue, too. When Detroit and Stockton went through bankruptcy, the cities managed to cut health care benefits, but pensions remained fully (Stockton) or mostly (Detroit) intact, in part, as Stanford Law's Michelle Wilde Anderson explains, for the same reasons pensions exist in the first place:

First, the plan authors in Detroit saw that cutting their retirees’ benefits would sink many retirees below the poverty line in the city and the region. This was a painful humanitarian reality, but so too was it an economic one: a municipal debtor has to be stable enough to pay its obligations under its bankruptcy plan. More concentrated local poverty does not help. A second main argument against cutting pension benefits showed up in Stockton. Officials determined that cutting benefits and thereby being excluded from the state pension system would make the city uncompetitive for public employees, especially police. That was a hard pill to swallow for a city with a spiking homicide rate and no cash to spare on competitive wages. Many other concerns surfaced in both cities as well, but they amounted to a bottom line determination that there were vanishingly few fat cat pensioners to be found, and the municipalities would be even worse off—as a debtor, as a city—if they cut into their retirees’ payments.

The Chicago Teachers Pension Fund has been paying between $70-$80 million a year in health insurance subsidies to retirees this decade. It's not a trivial sum, but it's not a lot to fight for in a process that could drive up borrowing costs.

Greg Hinz calls the bankruptcy trial balloon a "threat," which appears likely, as it seems impractical as a fix. The other alternative, state control, has happened before—and the state has a lot to learn from it.