Did you know? There's a plan to eliminate Illinois's budget deficit within a decade. It's not the grand bargain that's developing in the Illinois legislature, though it bears resemblance. It's from Richard Dye and David Merriman of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois, and it lays out five different things the state can do that, all combined, would eliminate the state's budget deficit by 2027, from around $13 billion now to a tiny surplus.

All of it would be unpopular. And, well, it wouldn't exactly eliminate the state's budget deficit, because it doesn't take into account the current $10 billion bill backlog—nor does it address the future bill backlog that would be created while the state whittles down its deficit.

But it's a good look at what sorts of policies could actually put us back in the black, even if the state doesn't implement this exact prescription in the end.

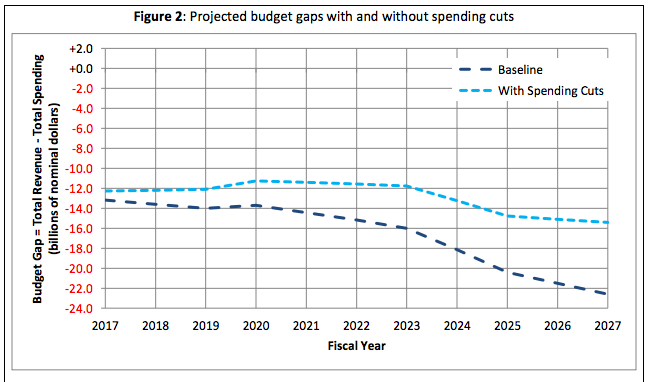

Cutting discretionary spending

The authors model what would happen if we cut two percentage points of spending growth, every year, through 2027. That's cumulative: after a decade, discretionary spending is down 20 percent.

"Discretionary," under their definition, includes things that they consider "operationally" required, even if they could legally be cut, like K-12 state grants, transportation spending, debt service, local-government transfers, and so forth. Those exclusions are two-thirds of state expenditures, reducing the dent a two-percent-per-year cut would make. Still, it adds up over time.

That's over $7 billion in the last year of the cuts, but it's gets us a third of the way back to break-even. And, as they note, "cuts of this magnitude on the remaining "discretionary" spending categories would be quite substantial and would undoubtedly result in substantial hardship to vulnerable populations if they were introduced on an across-the-board basis as we simulate here."

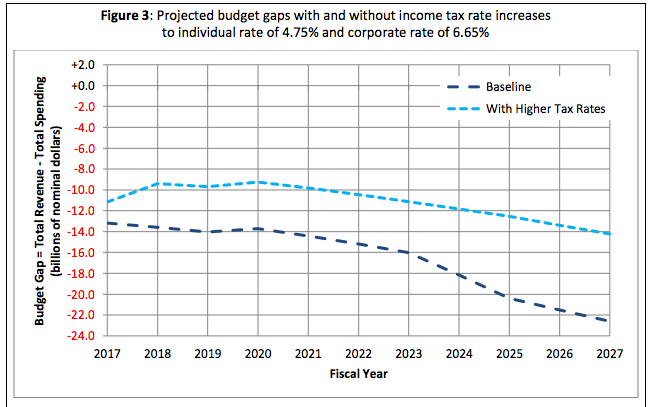

Higher personal and corporate income taxes

They estimate what would happen if the personal income tax was raised from 3.75 percent to 4.75 percent, and if the corporate income tax was raised from 5.25 to 6.65 percent (keeping the same personal/corporate rate ratio). The numbers floating around the grand bargain are different: raising the personal rate to 4.95 percent, with no indications that the corporate rate would go up, though unspecified loopholes would be closed.

Given that the individual income tax is a far greater revenue source than the corporate income tax—$15.3 million versus $2.4 million in 2016—their calculations aren't a bad ballpark figure.

Those are the two big components of their menu. In 2027, the spending cuts would reduce the budget gap by over $7 billion; the income-tax increase by over $8 billion. That's about two-thirds of what would otherwise be a $22 billion budget deficit—over three times what it is today—by 2027.

More ways to increase revenue

They chip away at the remainder of the budget gap with other revenue increases. Increasing the sales-tax base, something the governor has mentioned and also potentially a piece of the grand bargain, would close the gap by about $2 billion in 2027.

They also estimate clawing back about 40 percent of the revenue lost to other income tax exemptions, like retirement income, a K-12 education expense credit, and the residential real-estate tax credit. (Taxing retirement income is sometimes brought up as a faux pension cut, but eliminating tax exemptions doesn't seem to be part of the grand bargain.) That'd be almost $2 billion.

How much would income growth help?

Finally, they estimate what would happen if we got actual income growth, in theory the point of any "pro-growth" policy. They assume one-half of one percent growth every year, which doesn't sound like much, but is "quite different from past history and likely extraordinarily challenging."

That would add about $1.5 billion in revenues to the state budget in 2027, which would finally push the state into the black, assuming all their other estimates worked out—but would be the smallest component of their fix.

The outlines of their grand plan aren't what the grand bargain appears to be shaping up to be; in particular, it's hard to imagine the state cutting the growth of discretionary spending enough to reach 20 percent, even over a decade—in part because it would so affect the state's most vulnerable citizens. But even if it's a road not taken, it shows how steep an even longer road would be.