The other day, Chicago made the list of Amazon's 20 "finalists" for its second headquarters. This was in one of the first pieces I read about it:

"Cons: Shootings in the city have become national news, and the state is still emerging from dire financial straits."

Unsurprisingly, it wasn't the last piece about HQ2 to make this point.

NYT: "The city’s association with violence—it led the nation in murders with 765 in 2016—coexists alongside a cultural scene that features some of the most celebrated food and art in the country."

Crain's: "Violence and crime in Chicago have made national headlines."

WBEZ: "Every month it seems like President Donald Trump is tweeting about Chicago’s gun violence."

Tribune: "What’s more, we don’t know if the city’s reputation for violent crime will factor into Amazon’s thinking."

Tribune, again: "Another factor is violent crime. Chicago’s high number of shootings and killings, though mainly occurring in disadvantaged neighborhoods, is a red flag for Amazon and anyone else contemplating a move here."

USA Today: "Possible negative: An alarming if declining homicide rate"

Chicago has both a lot of violence and a lot of "association with violence" which has "made national headlines." Why's that? In part because it's in the headlines a lot. Who puts it in the headlines? Journalists… who then wonder about the effects of the city's association with violence.

Amazon might look at the headlines. But they will, presumably, look at the data, since that's what they're supposed to be good at. What does the data say?

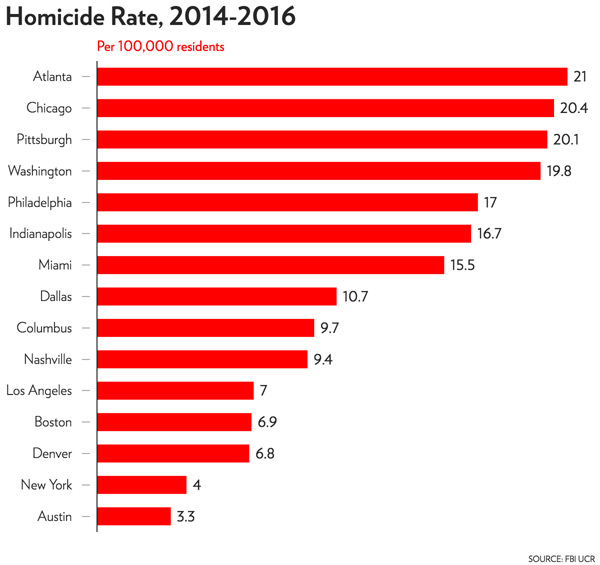

(I've eliminated Newark, Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill, Montgomery County, Northern Virginia, and Toronto from the list of finalists because of data-availability issues. All data is from the FBI's Uniform Crime Report and calculated against each city's estimated population in 2016.)

When The Trace looked at homicide rates for major cities from 2011-2016, Atlanta was above Chicago, and Philadelphia and Washington were not far behind; Pittsburgh and Indianapolis were farther down the list. But Atlanta's homicide rate doesn't seem to come up when it's reported on as a finalist, despite being bandied about as having some of the best odds.

Of course, homicide isn't the only crime to worry about. It's rare compared to other violent crimes and tends to group within social networks. How about all violent crimes?

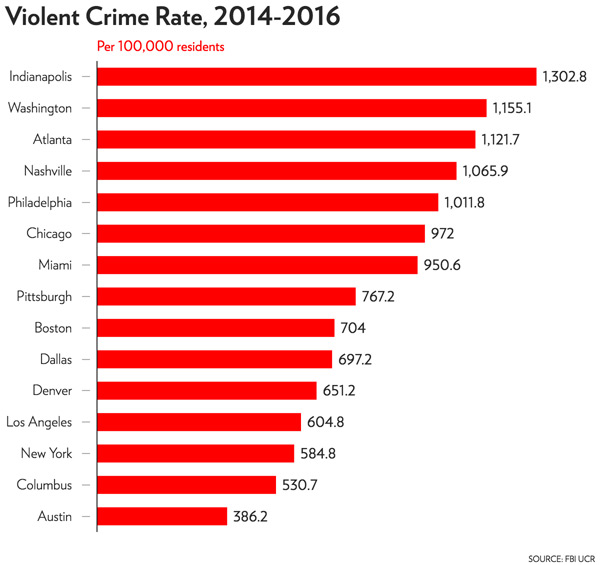

(It's worth noting that the FBI warns against using this data to rank cities, for a lot of good reasons, but if Amazon is looking at crime data, this seems like a likely place to start, so better to think about it in those terms than some absolute truth about the comparative violence in these cities.)

Violent-crime stats don't get the headlines that homicide stats do, but they're arguably more important to the average urban-dweller. Five cities, including conventional-wisdom-favorite Washington, are ahead of Chicago.

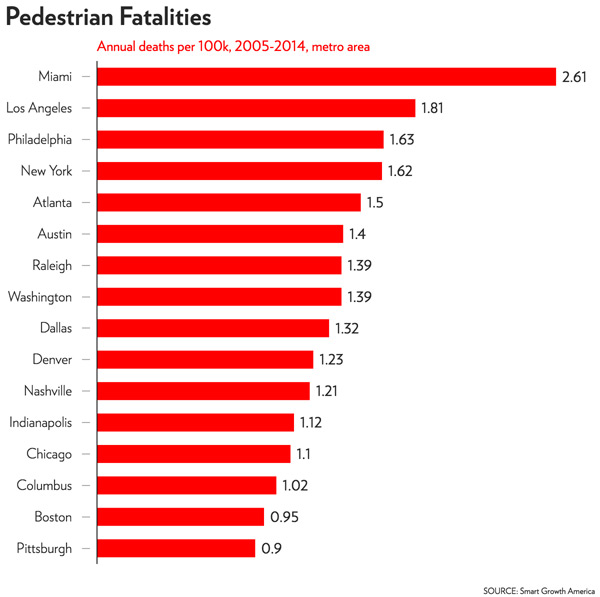

But what really doesn't get the headlines is people dying in car crashes—despite it being a common risk. Amazon says it wants "'walkability and connectivity between densely clustered buildings through 'sidewalks, bike lanes, trams, metro, bus, light rail, train, and additional creative options.'" Other motivations aside, getting its employees out of cars is another way thinking about their safety.

So how does Chicago stack up? Unfortunately, the best metro-level data I could find was from 2009. But here it is:

.jpg)

If you get employees out of cars, that raises other risks. Pedestrian fatalities has a much narrower range across the finalists, but we fare well there, too.

It's not that the headlines are undeserved, but they distort the picture. In some neighborhoods, it's a crisis; as Daniel Kay Hertz observed in 2014, the safest third of Chicago's neighborhoods have homicide rates comparable to the safest third of neighborhoods in New York City and Los Angeles, while the most dangerous third of Chicago neighborhoods are much more dangerous than its biggest-city peers.

“The conversation we are used to hearing is, 'Is a city safe?'” Hertz told the AP when it was investigating such neighborhoods in Indianapolis and Chicago. “But there’s no citywide statistic that tells you the story of a city.”

Chicago's story isn't even told through citywide statistics; it's told through headlines about those statistics, and then in stories based on those headlines. Amazon might drill down even further than the above data; hopefully, they'll drill down on what cities are or aren't doing about it, and how the company can help, such as devoting a modest boost of its property taxes for community mental-health clinics. But even just the basic data tells a different story.