Since becoming a parent I've gained a new appreciation for Chicago's parks. On Sunday, I went to the local park—just a block and a half away—twice, once for a couple hours in the morning and a second time to toddle my daughter through the fountains. It's a small park, far from the sylvan langour of nearby Humboldt Park, but a heavily used one; one weekend will bring a rugby match, the next a T-ball parade (complete with fire-truck escort), the next slackline hobbyists. Should we need or choose to leave the neighborhood, leaving the immediate vicinity of the park will be a tougher choice than the restaurants or the amazing coffee shop or decent corner grocery.

So I was a bit flummoxed to see Chicago come in a mere 16th in the Trust for Public Land's interesting new ParkScore index, which is constructed to compare park systems across cities. Minneapolis comes in at the top, because of course it does. Rounding out the top five are small, dense cities (New York, San Francisco, Boston) and another green western city (Portland). After that it starts to get surprising: Sacramento at #7? Virginia Beach, at #10, ahead of the city in a garden?

Well—as usual, it depends on the methodology. The TPL's methodology is pretty neat, and arguably it gives some sprawling cities due credit for a benefit of sprawl, the ability to create massive expanses of public land with considerable ease.

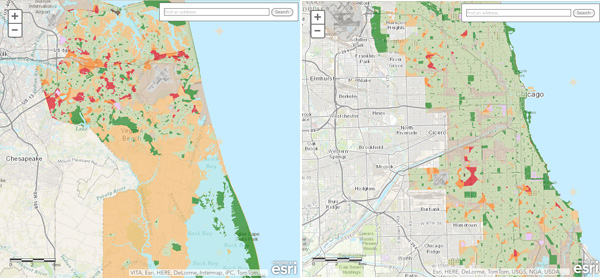

Take the case of Chicago and Virginia Beach, for instance:

Virginia Beach is astonishingly large: bigger than Chicago by 30,000 acres, about a quarter as large. Its median park size is twice as big, 4.1 acres versus 2.2—part of the ParkScore methodology. Two massive state parks within the city boundaries will do that.

But its access isn't very good:

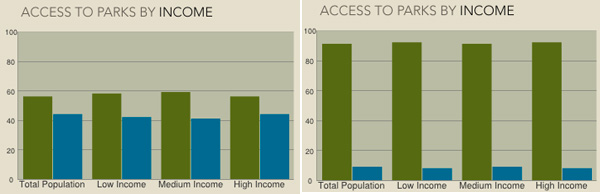

Access is judged on the proportion of the population within a 10-minute walk to a public park, or about half a mile. Chicago does very well on this count, with a score of 36 out of 40, but the differences at the top are pretty marginal. Chicago is at about 90 percent, and the cities above it range from 90 percent to just shy of 100. Of the cities ahead of it in access, only New York is physically bigger. (ParkScore removes "unpopulated railyard and airport areas from the baseline city land area," which, in Chicago, is a lot; all the gray areas in the above map) New York does it with small parks: the median park size in New York is half as big.

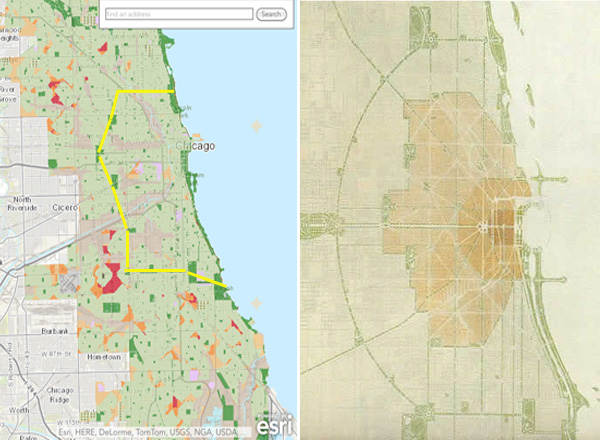

Chicago does quite well on park density in the center city; the "park poor" areas, as Blair Kamin has pointed out, are well off the lakefront. The dividing line between park-rich and park-poor is, or at least closely resembles, Daniel Burnham's plan for the city.

Burnham envisioned a series of large parks connected by green boulevards, and his ideas mostly came to pass. Here's a rough approximation of how the park-connecting-boulevards turned out:

(There was supposed to be a boulevard at Diversey connecting Lincoln Park to the west side, but politics killed it.)

Chicago was supposed to have better parks on the west sides of the city, but politics killed that, too. The landscape-architect genius who arrived on the scene was Jens Jensen, who developed a plan for a Greater West Park System. Jensen's plan was not just an expansion on the park system proposed in the Plan of Chicago; it was a response to it, specifically an aesthetic and political critique, as Jensen wrote in 1911 (via Robert Grese's Jens Jensen: Maker of Natural Parks and Gardens):

On the face of it, this idea of city planning is a fine thing—broad boulevards, ornate arches, formal promenades, all give one a feeling of excitement, as of being dressed in one's best clothes for some festive occasion. But right here is one of the most salient evils of such a city. It is too often a show city; it is at once the city of palaces and of box-like houses where humanity is packed together like cattle in railroad cars. To build civic centers and magnificent boulevards, leaving the greatest part of the city in filth and squalor, is to tell an untruth, to put on a false front, which vitiates the whole atmosphere of the town. The formal show environment reacts upon the people: the spirit of being on parade, of striving for superficialities, makes of them a city of spendthrifts desirous of a gay life.

Jensen's park system was remarkably forward-thinking. Rather than merely decorative, he planned what he called "municipal kitchen gardens," basically shared urban gardens of the kind that WBEZ's Odette Yousef profiled recently in Albany Park, and intended for the same reasons.

But the plan largely fell through. The parks commission blamed Jensen's "artistic temperament"—talking smack about Burnham probably didn't help—but Jensen's posse proposed a familiar culprit:

On the other hand, it is stated by friends of Mr. Jensen that policies may have played a part in the selection of certain laborers who hold minor jobs at the parks to the detriment of discipline and good service…. It is said also that Mr. Smulski has not agreed with Mr. Jensen’s ideas concering shrubs and flowers and park beautification, preferring landscape gardening of the old school.

Mr. Jensen is reported as being aggressively and militantly “nonpolitical,” and it is recognized that there is a constant pressure on the park administration from politicians seeking patronage.

Eventually Jensen got booted out for "a Lundin-Thompson organization man."

In that sense, perhaps Chicago's #16 ranking is fair. Within the city's core, there's equitable access that dates back to Burnham, an impressive density of parks for a city that's both dense and sprawling; outside of that, in the outer rings, there are areas that aren't as well covered. Had Jensen won his political war, perhaps Chicago would break the top 10, but urbs in horto is in historical tension with ubi est mea.