On a couple of occasions, I've written about the work of Marc Berman, a University of Chicago psychologist, on the concept of "attention-restoration theory," how it's grounded in the effects of green, natural space on the mind and the implications for that in how we design our surrounding environment.

The basic idea is simple: exposure to certain types of natural environments can restore our our ability to pay attention and reduce our mental fatigue. Green space essentially makes our brains more resilient and better able to deal with difficult tasks, such as doing academic work or taking care of a difficult child.

One of the pioneers in that work is a University of Illinois professor of landscape architecture, William Sullivan, and he has a new study out, led by graduate student Dongying Li, on one possible practical application: school landscaping.

Li and Sullivan are extending recent work by Rodney Matsuoka, who also teaches in UIUC's landscape architecture department. Matsuoka looked at 101 high schools in Michigan and found "consistent and systematically positive relationships between nature exposure and student performance," including graduation rates and how many students planned to go to a four-year college.

But Matsuoka's study was correlative; Li and Sullivan wanted to know about causation. So they set up an experiment investigating the effects of visual exposure to green space on stress and mental fatigue on high-school students in central Illinois. They set up shop in five different schools. In each school, one classroom had no windows, one had a "barren" view, and one had a view to greenery.

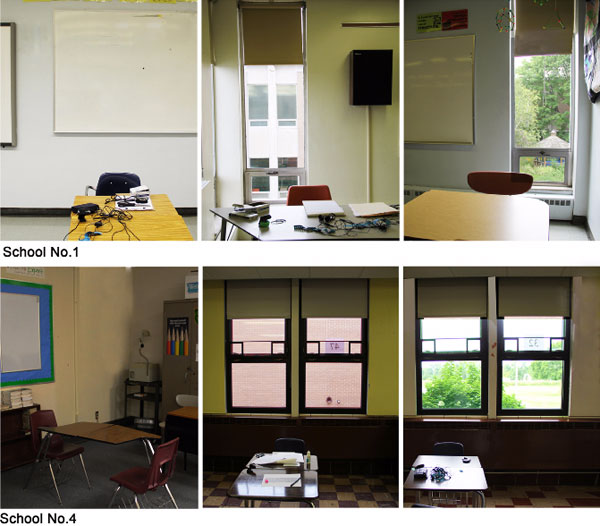

The green view was nothing special; we're not talking about a lush, perfect Frederick Law Olmsted expanse. Really, this is all it is.

They gave the students a stress test, had them work for half an hour, tested them again, gave them a 10-minute break—inside the classroom—and tested them again.

The results lined up with what you'd expect from attention-restoration theory. Physiological stress declined after the break for all three groups but declined most for the green-view group. For attention, the score increased after the break for the green-view group—but basically didn't change at all for the no-window and barren-view group. But the effects only kicked in after the break; having a view to green space didn't change stress levels during the work period.

Which really does line up with attention-restoration theory. Having exposure to green space—even just a view, for a relatively brief period—gives the brain a chance to restore itself and reduce fatigue, but you need a chance to actually take the green space in. Just having it around while you're working isn't enough, because the brain is focused on the task at hand. It needs that pause that refreshes.

I spoke to Li and Sullivan about attention-restoration theory, how the study fits into it, and the implications for how we can use it to better build our environment.

What is attention-restoration theory?

Sullivan: It's a really robust and helpful theory. It says, in essence, that you have two modes of attending to things. One is what we call involuntary, and the other we call directed attention, or what normal human beings call paying attention. You can look at each of those two kinds in terms of two dimensions. One dimension is the amount of effort it takes. Involuntary attention takes no effort at all; if a hawk lands outside your window right now, your attention's going to be called to it.

There's many, many things like that. Waterfalls, fires in a fireplace, wild animals, babies. There's another kind of attention, directed attention, paying attention. That does require effort. The work that you're doing right now, listening to us, the next piece that you're going to write, that takes effort on your part.

The first kind, involuntary attention, doesn't fatigue. You can look at that fire in the fireplace for a long, long time, and you won't get tired. You might get bored, but it's not going to fatigue you. But writing a proposal to write your next book, or working on a budget for some project, that kind of attention, using that directed attention, does fatigue.

The reason it fatigues is pretty clear. When you decide to pay attention to something, your brain works to exclude two sources of competing stimuli. One source of competing stimuli is all the stuff that's going around you in the physical environment. The conversation down the hall, the smell of popcorn someone's cooking two doors down, all that stuff can come into your attention and fight with you for your focus.

The second source of competition for your attention while you're focusing on the work at hand is all the stuff running around in your head in one moment. All the stuff that says, Hh my goodness, I forgot that deadline, or forgot to pay that bill. This top-down attention mechanism keeps that stuff at bay, and allows us to add salience to whatever we're focusing on in the moment.

The problem with that mechanism is that it fatigues. For me, I have a good hour in the morning when I can focus hard, often I can focus really well for an hour and a half. But after that 90 minutes, I find I need a break. I have to stop my writing, editing, analysis work. That mechanism is starting to fatigue. It's taking increasing effort just to focus on what, an hour ago, didn't seem to take much effort to focus on at all.

The brilliance of attention-restoration theory is to say that physical settings contribute to our use of attention, directed attention, and to our capacity to recover from mental fatigue when that mechanism is fatigued.

Why is it that natural views are especially good for attention restoration?

Sullivan: I think the consensus is that they're softly fascinating. You can think of fascinating things along a continuum. Some sporting event that you're deeply fascinated in—that's hard fascination. There's not much space in your head other than what's happening in the next few seconds in this particular game. Movies are like that too. With a captivating movie, you don't have time to ruminate on what you're going to do tomorrow. You're totally sucked up into the story. That's referred to has hard fascination.

At the other end of the continuum, looking at a campfire for instance, or taking a walk in the woods, that's pretty soft and fascinating. It leaves you engaged with the activity, but there's still a lot of space in your head to have things bubble up. You can gently ruminate, think about the issues you're dealing with, think ahead. I think the notion is that natural environments, or even urban environments that include green infrastructure, are softly fascinating, but they don't demand us to use that top-down mechanism. And have the added benefit of not completely filling our head.

It's been interesting to me, following the research, is that I immediately went to the idea of evolutionary psychology…

Sullivan: Like Gordon Orians's work on landscapes and habitat selection? It's fascinating. It talks about how any animal that can move seeks out any habitat that is most conducive to their survival and reproduction. It's kind of the foundation of habitat-selection theory. Animals that can move seek out and compete for favorable environments. I think Orians and [Rachel and Stephen] Kaplan would argue that humans are hard-wired to function effectively in natural settings. And therefore our brains respond to them differently than intensely urban environments.

What was interesting to me about your study is that the exposure to green space was not that intense.

Li: We followed up with the Matsuoka study because, for one thing, he measured school-wide student performance. It's a correlational study. There can be other things effecting school environment and school-wide student performance.

Sullivan: He couldn't prove cause and effect.

Li: We tried to figure out if we could establish a causal relationship between views onto green space and students' attentional capacity, and how they would perform in tests.

Sullivan: We did a randomized, controlled experimental design, in which we randomly assigned kids to three different kinds of classrooms in their own high schools. That kind of study has a great strength in terms of proving causality, but it's less ecologically valid than the Matsuoka study that looked at 100 high schools over a much longer time frame. But together, the weaknesses and the strength of the two studies combined start giving you a sense that, my goodness, there's something really interesting going on here, and maybe the findings have implications for how we design schools and school neighborhoods.

How does it work in terms of causation? You found two pathways in which it does.

Sullivan: We wanted to test two pathways because both could be impacting students and their capacity to learn. A student that is mentally fatigued is not as good a learner as the same student who is less mentally fatigued. And the same is true for stress. If a kid is less stressed, she's in a better state to learn.

But there's an underlying, geeky reason to do it too. There's some discussion in the literature, some debate, whether stress leads to mental fatigue. Or whether mentally fatigued people end up being physiologically stressed. This research allows us to look at the main effects and interactions, and to see mental fatigue was mediated by stress, for instance. It gave us a nice research design to explore these various ideas, some of which have policy relevance, and some of which are relevant only to geeks.

Was there anything that surprised you in the results?

Li: What was surprising for me was that during the class activities, the window view doesn't matter. But when the students are taking a break, it matters a lot if you have a green window view.

Sullivan:If you look at the charts in the paper, you'll notice that at the end of the period in which they were engaged in the academic activities, and we tested it after they paid attention, there were no differences in the students in the three kinds of classrooms. So while they're focusing on the work at hand, we found no impact on the setting on their attention function.

But after the 10-minute break, there is a significant measurable boost for the kids on the green room, while the kids in the barren room, and the room with no window, it was like they didn't have a break at all.

I thought about how when I was in college, and spring came, teachers would be like, let's all go outside and have a class! And I always found it very difficult to concentrate.

Sullivan: Oh my goodness, going outside for class is a huge waste of time, if your intention is to teach anybody something. Here at the university, I see people outside in the quad—and it's almost always graduate students taking kids out—and I'm just thinking, It's impossible to get anything academic done in that setting. Because it's so rich with stimuli, especially if you've been cooped up all winter. It's nearly impossible to concentrate. There are way too many demands on your function.

While you're trying to concentrate, what you want in that situation is a setting with few distractions. Not much or no noise, no elements in the physical environment that compete for your attention. If you try to go into that kind of setting and focus, it's going to generate a lot of mental fatigue. Because you're going to be fighting against the constant urge to see who's walking by, to watch those birds, smell the barbecue over there, or whatever's going on.

I was surprised that the green space environments, there was nothing dramatic. Just a typical view.

Sullivan: None of the settings would make a photo that would be reproduced in Chicago magazine, or National Geographic. They were not in any way spectacular or wonderful. They were just everyday examples of exposure to nature.

When you talk about possible policy implications, one is obviously how we design these spaces. It seems to suggest that they don't have to be dramatic interventions.

Li: Our group has a study suggesting that trees at people's doorstep might be more significant in bringing health benefits than parks in central locations.

Sullivan: We've invested huge amounts in Chicago in Millennium Park, or the new Northerly Island park, or even the 606 park. Wonderful cities have great parks like Millennium Park and Northerly Island. But it's clearly not enough. It looks like what you need is nature at your doorstep. You need nature out your window. And what neighbors need is green space that pulls them outside that increases the opportunity for them to see each other.

When neighbors see each other, they begin to recognize each other, they begin to treat each other as neighbors. Greener neighborhood spaces are really important in terms of developing neighborhood social lives. While parks are great, and we have to have them, and they're necessary, they're not enough. They're not sufficient to create healthy individuals and healthy neighborhoods.

Comments are closed.