Earlier this year, Mayor Rahm Emanuel stood beside CTA president Dorval Carter in Roseland’s Block Park and tried to convince a gaggle of reporters that a 5.3-mile southern extension of the system’s Red Line—a project Far South Side residents have been promised since the 58-year-old mayor was in grade school—is really going to happen this time.

“I’m confident we will… secure the resources because of the significance of the project and the investment the city is willing to make,” Emanuel said of the $2.3 billion endeavor, according to the Sun-Times.

Emanuel and Carter stood before a blown-up map showing a projected alignment for the new route, which would hug existing Union Pacific and Metra Electric tracks before ending at the city’s southern border at 130th Street. The alignment—plus the $75 million the CTA has already laid down for an official Environmental Impact Statement—show the city is serious, officials said.

It would be the first time since the completion of the Orange Line in 1992 that the CTA built a new stretch of track. But it would not be the first time since 1992 that the CTA has tried to do so.

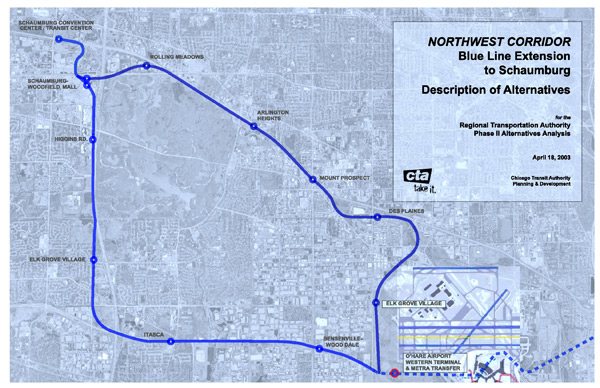

On the evening of May 8, 2003, neighbors milled through the alumni building at Roosevelt University’s Schaumburg campus and squinted at a blown-up map showing a dotted blue line starting at O’Hare Airport and ending a few blocks from where they stood. At the top of the map was the CTA’s Helvetica logo, alongside its graffiti-style early-2000s tagline: “Take it.”

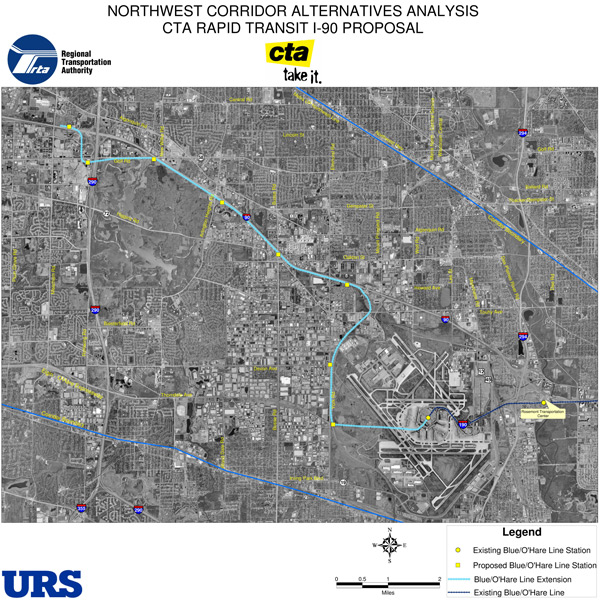

The CTA was one of three transit agencies asked to draw up plans for new infrastructure along the region’s northwest-suburban corridor, then—as it is now—one of the fastest-growing regions in Illinois. Tacking another 10.5 miles onto the Blue Line, which had been extended to O’Hare in 1984, was what they came up with.

“Looking back to the ‘90s, there was an explosion of development along the Northwest Tollway corridor, with a lot of new offices and industrial capacity in Elk Grove Village and Schaumburg,” said Larry Bury, deputy director of the Northwest Municipal Conference, a coalition of 45 suburban mayors.

“There was clearly a great need for providing additional transit services, to handle all these new commuters coming into the area,” said Bury, then a member of the group’s transportation committee. “So we coordinated with the [Regional Transportation Authority] and all the municipalities in that corridor to start getting some detailed reports on how to get new ridership going.”

CTA planners published a 54-page analysis of the proposal, first dreamed up in the agency’s 1998 “Destination 2020” strategic plan. The plan mapped out two routes, each of which would stop at six suburban stations before pulling into a terminus at the Schaumburg convention center.

But when it came time to choose the proposal they liked best, mayors like Al Larson of Schaumburg, one of the transit campaign’s loudest backers, liked Metra’s plan better.

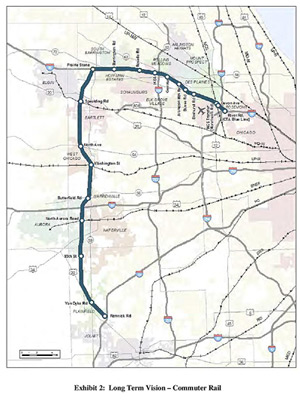

The Metra Suburban Transit Access Route, or Star Line, would run from O’Hare to northwest suburban Hoffman Estates, then loop back south to Joliet.

“There was talk of a high-speed Blue Line, but I don’t think that was ever as seriously considered as the Star Line, which a lot of communities saw as really viable,” said Larson, now in his eighth term as mayor. “You had even had towns putting aside land for future stations, and developing around where they thought the stations would go.”

The Blue Line extension also met political resistance from within the city, according to Jon Hilkevitch, who covered transportation for the Chicago Tribune from 1996 to 2015.

“[Mayor Richard M.] Daley was never really behind the Blue Line,” Hilkevitch siad. “The CTA had enough problems on its existing lines, which include track going back to the 1800s, and it still does.”

But almost as soon as Metra started formal planning for the Star Line, they ran into their own set of roadblocks.

Surveying revealed natural gas lines along I-90 that Metra would have to pay to relocate. The Canadian National Railway company bought the Elgin Joliet & Eastern railway, imperiling the proposed western leg of the route. In 2010, Metra CEO Phil Pagano, one of the Star Line’s key architects, stepped in front of a morning commuter train.

But it wasn’t until Metra started applying for federal funding—the stage in which libraries full of transit proposals have met their ends—that the $2.7 billion Star Line proposal finally died.

“The alternatives analysis was completed, but then we had to put together a financial analysis, showing that we’d be able not just to build it, but to fund it,” Metra spokesman Michael Gillis said. “That’s where it got held up. Every year, we had the same problem: there just wasn’t enough financial wherewithal to move forward.”

In the past 20 years, the faucet of state and federal funding for Chicago transit projects has only shrunk. New Start, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s hallmark transit grant, slid from covering 80 percent of the cost of new rail projects to just half.

The city can no longer rely on political heavyweights like former House Speaker Dennis Hastert and Rep. Dan Rostenkowski to haul earmarks back from Washington, and Springfield’s transit funding has slowed to a trickle since the state passed its last capital improvements package in 2009.

The aborted Blue Line and Star Line proposals offer a cautionary tale for those who are hopeful for the Red Line extension, according to author and transportation researcher Joe Schwieterman, who leads the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development.

“It’s remarkable that we haven’t had any mega-projects move ahead on the transit side, but the combination of slow population growth and looming budget woes have undermined so many great ideas,” Schwieterman said.

But the Schaumburg extension saga may also show a way forward for the transit-starved Far South Side, he added.

Last year, the Pace suburban bus agency launched an express bus lane along the Jane Addams Tollway, a route Larson has called a “mini Star Line.” The route has led to an explosion of new ridership along the corridor, according to Pace officials.

“The Red Line extension solves a problem of inequitable transportation, but the costs are likely out of proportion with the benefits,” Schwieterman said. “There are so many other ways to serve that region, like better bus service, at a fraction of the cost.”

Pace had offered its own plan in 2003 for a “bus rapid transit” system along the northwest corridor, brandishing sketches of spaceship-like “trains on wheels” as an alternative to the Metra and CTA visions.

Suburban mayors swatted Pace’s proposal aside because of a universal “perception that upper-middle class suburbanites just wouldn’t ride buses,” no matter how sleek they looked, according to Hilkevich.

But Pace was well-positioned to pick up the pieces from the crumbled rail projects, according to Pace spokeswoman Maggie Daly Skogsbakken.

“Rail is expensive and would cost billions to implement,” Skogsbakken wrote in an email. “Bus service is a flexible, affordable service that can respond and change as needed when a region grows.”

Still, CTA leaders insist the Red Line rail extension is moving ahead full-steam, far beyond the stage that saw the Blue Line plan break down in 2003.

“The Blue Line study never passed the conceptual stage and at no point were ‘funding and interest’ discussed,” CTA spokesman Steve Mayberry wrote in an email. “By contrast, the Red Line Extension is a real project—not a conceptual proposal—that is proceeding through the federally-required initial planning and analysis phases.”

Another glimmer of hope for the project comes from the omnibus spending budget passed by Congress this week, which includes a surprisingly hefty $2.64 billion for New Start transit funding around the country.

And despite the herculean funding effort still faced by CTA planners, 50 years’ worth of pent up political pressure may just be enough to push them past the finish line, Hilkevitch said.

“We’re talking about something that’s been promised to the black community for half a century, and meanwhile Mayor Emanuel is surrounded by critics asking why the North Side is getting all the projects,” Hilkevitch said. “So yes, I think the extension will happen. But it won’t be any time soon.”