The last chapter of Ebony magazine’s storied history in Chicago got a final footnote last week when the publication and its Texas-based owner reached a settlement with about two dozen freelancers and agreed to pay them nearly $80,000 worth of delinquent invoices.

The public, and at times bitter, feud drew widespread attention on social media with the #EbonyOwes campaign. Dozens of black creatives, many of whom grew up admiring the brand, tweeted regularly to remind the public (and Ebony brass) that the iconic black lifestyle magazine had stiffed them on payment.

Several of the plaintiffs who spoke to Chicago described a mix of emotions from relief (some were owed in excess of $6,000) to resigned sadness; no one, they say, ever wanted to have to sue a magazine they held in such high regard.

But the way #EbonyOwes was resolved also serves as a valuable lesson to legacy media brands. Some publications, like Ebony, have long relied on freelancers for the bulk their content. And as shrinking magazine and paper staffs force more of the labor force into being independent contractors, freelancers are getting organized.

AJ Springer, a D.C.-based writer, says he’s “incredibly happy” with the outcome. Springer’s payment, among the most outstanding, was invoiced in mid-2016. What he’s happiest about, however, is what he hopes will be a new precedent in the industry.

“Because we were loud and did not take this quietly and solely handle it in the courts, I hope it shows people that freelancers don't have to accept non-payment as the cost of doing business—whether it's from a startup or a legacy publication,” Springer says. “I want this to go down as the example that freelancers can not only fight, but also win when we organize.”

Several of the freelancers say they thought they were the only ones not getting paid and felt they had little power, especially once Ebony’s accounts payable representatives stopped responding to their queries. Once the freelancers saw the breadth of the problem—due largely to the #EbonyOwes campaign—they were ultimately able to organize with the National Writers Union.

Finding other freelancers in the same situation wasn’t the only challenge. Tiffany Walden, an Ebony freelancer who co-founded and serves as editor-in-chief of Chicago’s young black-interest outlet The TRiiBE, says challenging Ebony stirred real internal conflict.

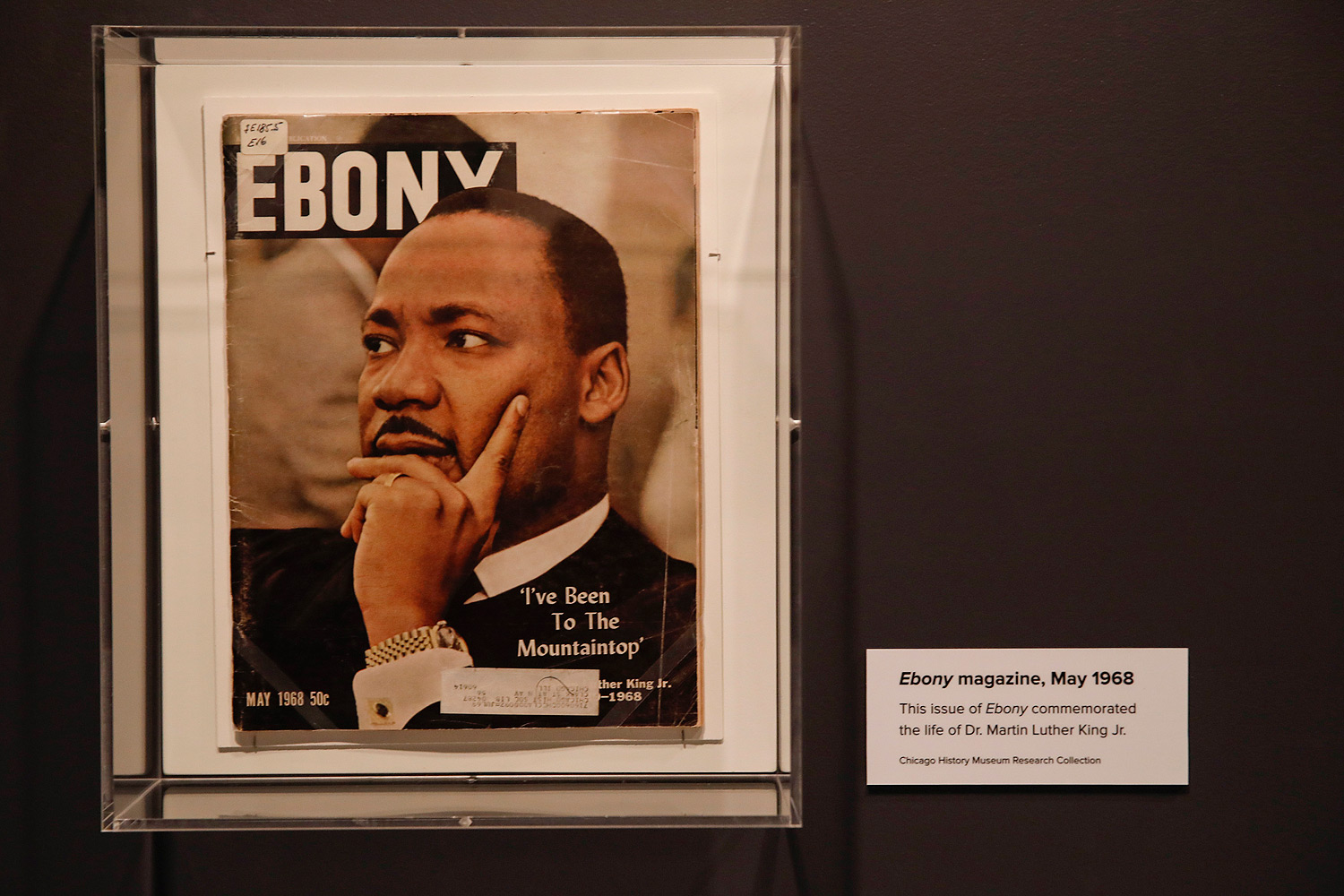

“Ebony magazine is black Chicago history. It’s black history period,” Walden says. The lifestyle-focused Ebony, along with Johnson Publishing’s weekly digest, Jet, were go-to publications of the civil-rights movement; the latter famously published photos of Emmett Till’s mutilated body, sparking a conversation about the state of racism in American.

“Ebony’s been a stalwart in the community for so long—something our grandmothers and parents grew up buying and reading and subscribing to,” Walden says. “It felt like I would be a traitor if I said, ‘look, Ebony magazine isn’t paying me.’”

Walden and others say they worried they would be accused of trying to tear down an iconic black institution, especially at a time when so few black-owned and black-oriented media organizations exist.

“The black journalism community is a small community. I didn’t want to come off as someone who was a rebel-rouser or someone who was blowing things out of proportion,” Walden says.

Per terms of the settlement, Ebony and its private equity firm owners, Clear View Group, will pay the freelancers without admitting to any wrongdoing or confirming the plaintiff’s allegations.

“They know they’re getting off cheap: if they had gone to court, there’d be interest added on. And it’s a fraction of the freelancers,” says National Writers Union president Larry Goldbetter, noting that the number of unpaid Ebony freelancers is likely twice the number of actual plaintiffs who joined the suit.

The Chicago-based Johnson Publishing Company sold Ebony and Jet—its print version defunct—to CVG in 2016 for an undisclosed sum. Months after the sale, Ebony continued to hit newsstands, but subscribers weren’t getting their magazine deliveries.

Meanwhile, Walden says payments slowed down but still came in. And, she notes, Ebony executives were still conspicuously spending cash on parties and events, as evidenced by their own social media posts.

Walden says she emailed her editor, Adrienne Gibbs, hoping to get answers. Gibbs, a Chicago-based former Ebony staffer who in recent years oversaw some of the magazine’s biggest special issues as a freelance managing editor, says the magazine was never clear-cut on where the freelancers’ money was.

“A lot of [freelancers] thought it was happening to them individually—and a lot of them thought the check was in the mail. And at that point, accounts payable was responding saying it would be paid by a certain time,” Gibbs says. “For me, people were cc-ing me on emails they were sending to accounts payable. And when accounts payable stopped responding, people would ask me privately what was happening.”

Because payments slowed but didn’t stop completely, it was unclear to a lot of the freelancers if and how they should escalate the situation, especially since many of them planned to continue freelancing for Ebony.

“Payments were a week late. Or two. Then they stopped. It was like a faucet being slowly shut off,” Gibbs says.

She ultimately played a strong role in organizing the freelancers, many of whom she had recruited to work on Ebony special issues.

“It was appalling. And I can’t have my name mixed up in that,” Gibbs says. Like Walden, her decision wasn’t easy, either.

“Having Ebony on my resume is a tremendous source of pride. I created columns, franchises, planned the 50th anniversary party…” Gibbs says. “Being in church, people would say ‘there goes Adrienne, she’s writing for Ebony; lets pray for her, let’s pray for her stories.' It was really difficult for me to decide to go this route.”

Walden says despite the public battle and the settlement, the freelancers largely have their ire directed at the people managing the Ebony brand.

“They represented a brand that was larger than themselves, and sullied it. But I still hold the brand in my heart,” Walden says. “I wouldn’t have started The TRiiBE without [Ebony and Johnson Publishing founder] John H. Johnson.”

“I know for sure John Johnson would’ve made sure everyone got paid, or else he wouldn’t have hired them,” Gibbs adds.

Goldbetter says the issue of late payment and non-payment is widespread in the freelance industry. Because the freelance labor force is growing, he hopes freelance payment laws like the “Freelance Isn’t Free” act, which went into effect in New York City last year, will spread.

“I think it’ll be city-to-city before it goes state-to-state. The passage of the law in New York was kind of the right moment, with a progressive mayor and a progressive city council.”

He predicts the #EbonyOwes settlement will have an even larger impact than the recent victory the union won for freelancers of Nautilus, the award-winning science magazine with a similar history of shorting writers.

“We’re torn having to say these things on social media,” Walden says. “But in this age, if you don’t say things on social media, Ebony would still be doing this. It’s not us damming Ebony magazine itself. It’s a pillar and a period in black history, but it’s the mismanagement we’re disappointed in.”