How much is inequality in the news? So much so that Benjamin Page, a veteran political scientist at Northwestern with the wonderful title of "Gordon S. Fulcher Professor of Decision Making," was invited to The Daily Show with co-author Martin Gilens to plug and discuss an academic paper. Not a popularized crossover book; not an academic tome; a journal article. Jon Stewart is known for opening up the TDS show to academics, but even by his standards a journal-article promo is deep in the weeds.

In truth, Princeton's Gilens is really the star, so to speak, here; he's the primary author, and, as they both acknowledge, did the vast bulk of the effort on the piece, "Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens."

You may have already come across their work in news reports with exhausting headlines like STUDY: U.S. IS AN OLIGARCHY, NOT A DEMOCRACY. But if America was actually an oligarchy—Gilens and Page use the term "elite economic domination"—their job would be a lot easier, since their subject would consist of a lot fewer people who would pretty much get what they want. (Tl;dr version: instead of an oligarchy we have "biased pluralism" with "economic elite domination," which I will grant sounds less sexy.)

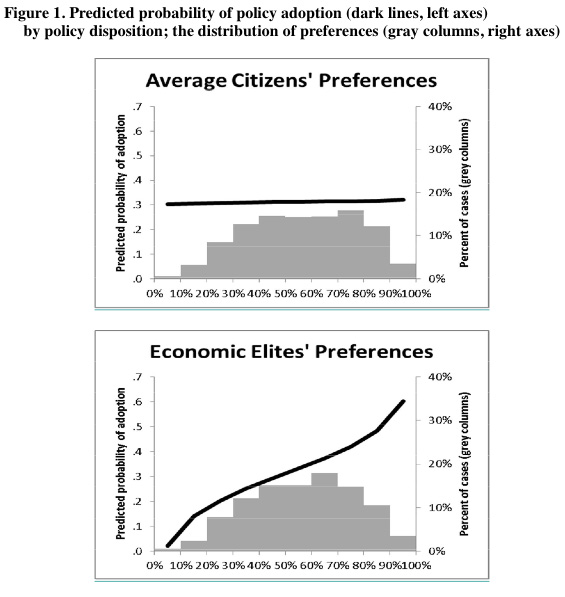

What Gilens and Page do, using ten years' worth of data collected by Gillens and his research assistance, is gather "a large, diverse set of policy cases: 1,779 instances between 1981 and 2002 in which a national survey of the general public asked a favor/oppose question about a proposed policy change." Those opinions are then assesed by income level to estimate the opinions of the poor (10th percentile), middle class/average/"median non-institutionalized adult American" (50th percentile), and "fairly affluent" (90th percentile), the last of which correlates pretty well with the much more than fairly affluent. Then they matched those opinions up with actual policy change.

Envelope please:

As Gilens and Page point out, this doesn't mean that average citizens never get their way—in fact, there's substantial correlation between the preferences of the average citizen and the economic elite. Nor does it mean that the economic elite always get their way; at best, i.e. when both economic elites and interest groups strongly favor a thing, that thing happens about 56 percent of the time.

What it does suggest: "When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites and/or with organized interests, they generally lose. Moreover, because of the strong status quo bias built into the U.S. political system, even when fairly large majorities of Americans favor policy change, they generally do not get it."

And this, perhaps, goes some way towards explaining why a lot of policies that will look very familiar exist—and that's where Benjamin Page's work comes in. If you're remotely familiar with the Chicago School of sociology, you're well aware that we have staggering amounts of knowledge about the poor, going back to the origins of the field.

The very wealthy are more mysterious to academic study, not least because they're very hard to pinpoint. When Page wrote up his pilot study on the political and policy beliefs of a handful of very wealthy Chicagoans, it began with a fascinating (if you're into that sort of thing) account of the hurdles involved in actually building the sample from available data. (There's an interesting parallel study out of Boston College.)

Page's initial work, again a small sample, points towards an understanding of the policy preferences of the extremely wealthy. 87 percent ranked budget deficits a very important problem; 16 percent ranked climate change as very important. 79 percent ranked education as a very important problem; 56 percent ranked child poverty.

Numbers like this are where Page's work could be quite significant: if, say, you believe that education and child poverty are inextricably linked, then that 23-point gap is worrisome, because of the trends identified by Gilens and Page. And it's also a target for action.

(Then again, if Page's sample reflects the greater reality, support from the very wealthy isn't a magic bullet: in terms of spending priorities, the biggest gap between "expand" and "cut back," on the "expand" side, was "improving public infrastructure," and that hasn't been going so hot. The biggest gap on the "cut back" side was farm subsidies. Again, not a magic bullet. Of course, Chicago, as an economic entity, is really dependent on infrastructure, and Page's sample has an obvious regional bias.)

And that's where Page's and Gilens's work intersect, besides their collaboration: the paper that Gilens and Page discuss on TDS is crunching the numbers for correlation, while Page's nascent studies on the beliefs of the rich is an attempt to trace those results back to their origins.

(Extended interview here.)