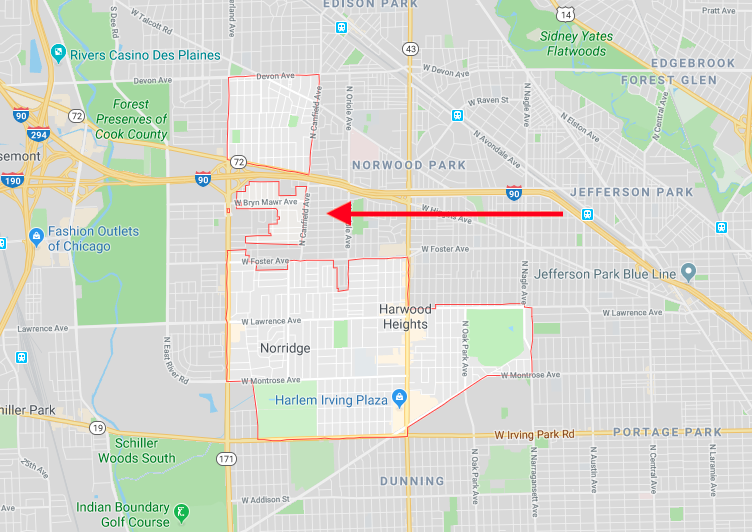

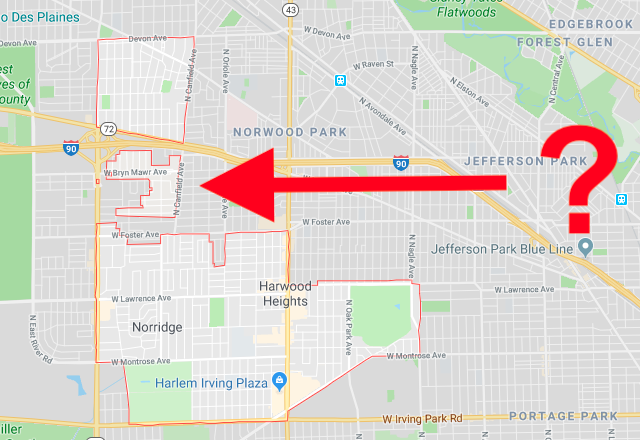

Look at a map of Chicago, and you'll notice a little hole on the Northwest Side — a few blocks, shaped like a backwards C, between Oriole Park and the Cook County Forest Preserve.

That's unincorporated Norwood Park Township, a leftover piece of land that never joined Chicago or its quasi-suburban neighbors, Norridge or Harwood Heights.

Unincorporated Norwood Park Township is best known as the home of serial killer John Wayne Gacy, who buried dozens of boys in the crawlspace of his home at 8213 West Summerdale Avenue. The neighborhood, though, prefers to advertise itself as “An Island in the City.”

UNPT, as we'll call it for short, is kind of a pain for Cook County. The township has no police force, so the county is required to patrol it with sheriff's deputies, along with 51 other miles of unincorporated land.

When she took office in 2011, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle set a goal of eliminating all unincorporated land by the end of the decade. But UNPT is still there, freeloading police protection off the rest of the county.

It's not just urban counties that find remnant townships burdensome. Some rural counties want to get rid of their townships, too. Last month, State Rep. David McSweeney, R-Barrington Hills, passed a bill that would allow McHenry County townships to dissolve themselves.

“My goal is to reduce the number of governmental bodies — it’s one of the reasons our property taxes are so high,” McSweeney said. “Consolidation, I think, is the key to reducing property taxes and administrative fees.”

Here's a bigger, better idea: let's get rid of every township in Illinois. All 1,428 of them — a big reason the state leads the nation in number of taxing bodies. Townships are an obsolete layer of government that has no place in the 21st century. Most states get along fine without townships, including all the low-tax, high-growth states of the Sunbelt. Illinois can learn to live without them, too.

A hyper-local form of government peculiar to the Upper Midwest, townships were established by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 as a method of selling land to farmers. Typically 36 square miles — six miles to a side — townships suited rural residents who couldn’t ride their horses to the county seat and back in a day.

But long after the land has been settled, and horses replaced by cars, townships are still with us. Their only governmental functions are road maintenance, aid to the poor, and property tax assessments. Cities and counties could do all those things, better and more cheaply. (McSweeney's bill requires that property taxes for functions formerly performed by a township would drop 10 percent.)

In a report titled “Why Townships Don’t Add Up,” the Better Government Association concluded that townships are wasteful and redundant:

There’s already a county assessor, so why have separate township assessors or assistant assessors? Roads get plowed and maintained by overlapping municipalities or the state, so why do the township road crews do it too? And general aid and assistance to the poor is handled by a plethora of government-supported human services agencies, so what exclusive support role do townships perform?

In 2013, Evanston Township voted itself out of existence — the first Illinois township to do so since 1932. Since the township's borders were coterminous with the city, and the aldermen also served as the board of supervisors, nobody misses it. In fact, absorbing the township's functions into the city saved property owners $250,000. (The high school, however, kept its Evanston Township name.)

Like most Illinois counties, Cook was originally platted with a grid of townships. The townships now contained by Chicago, including Rogers Park, Hyde Park, and Lake View, passed out of existence upon annexation. In the suburbs, townships still exist, even if all their land has been incorporated. In Cook County, remnant unincorporated bits of township could be required to join the nearest municipality, which would then take over township duties, as Evanston did.

There’s a saying that bureaucracy perpetuates itself, and that's certainly true of townships. They're so hard to get rid of because they're a juicy source of jobs, patronage, and double-dipping for elected officials.

Take state Sen. Steve Landek, who climbed the political ladder by serving as Lyons Township Road Commissioner, which required him to oversee a grand total of 20 miles of roads on unincorporated suburban land. Landek left that job to become Lyons Township Supervisor, a job he briefly held onto while also serving as mayor of Bridgeview and Illinois state senator. (Landek's predecessor in the senate, Lou Viverito, simultaneously served as Stickney Township Supervisor.)

Townships even have their own Springfield lobbying group, the Township Officials of Illinois, whose executive director, Bryan Smith, recently wrote in a letter to the Sun-Times:

"…in Illinois, the smallest local governments generally spent half as much per capita as those with local governments of populations between 10,000 to 250,000 residents. That means Illinois taxpayers will likely be required to pay more if their communities are required to assume the duties of township government because of consolidation or elimination."

More government = lower taxes sounds like an Orwellian argument, especially in a state with the most government and, according to USA Today, the fifth-worst tax burden in the nation.

Townships certainly aren't to blame for all of that, but given how easily their duties could be absorbed by overlapping governments, getting rid of them is a good place to start.

Comments are closed.