This summer, the city put out a call to all taxi drivers and passengers—it was determined to find Chicago's Top Cabbie.

Five hundred nominations or so came in; some cabbies were more self-promotional than others (one enterprising driver even handed out slips of paper with the contest information), and the city's panel whittled a field of 86 cabbies down to 12. Voting ended last week.

Considering the grand prize—a taxi medallion, or license—it was a surprisingly low turnout among the city's 12,000 or so licensed taxi drivers. Though the winner is yet to be crowned, the lukewarm interest in an item that once would have been coveted is a pointed example of how decimated the industry is becoming.

Sean Farkye, a Ghanaian taxi owner-operator who acquired his medallion nearly two decades ago, says that the license that once gave him “a little independence to be able to live the American Dream” now feels like a dead weight.

“The taxi industry is being overregulated, and taxes are going up and ridership is going down, [and] at some point nobody would like to own a taxi medallion in the city,” says Farkye, who is a member of Cab Drivers United, a union that has been advocating for better conditions for drivers and stricter regulations on competitors like Uber and Lyft. “It’s just gonna be a headache—you have to buy your own car, pay a lot of taxes, ground transportation taxes. Some people don’t want to be bothered with it anymore.”

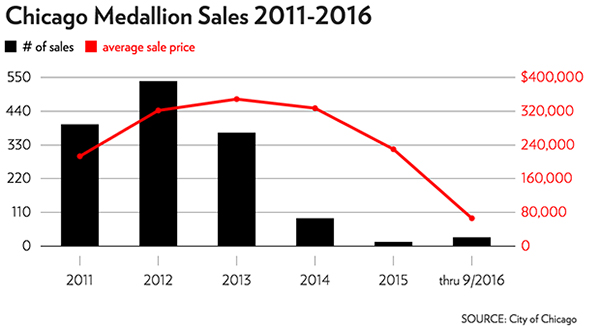

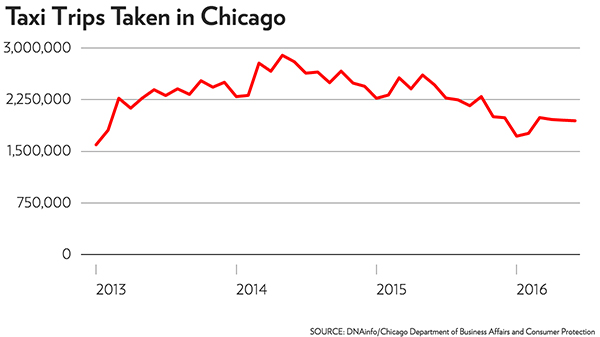

Over 70 percent of Chicago’s taxi drivers are first-generation immigrants like Farkye, according to a CDU survey. Driving a taxi, sometimes paired with owning one’s own medallion, or license, was long viewed as a way to work into the middle class. That narrative is now falling apart; just three years ago, the city announced an auction of 50 medallions for a base price of $360,000 each; this year, the average value of a medallion transaction has been $66,458. Taxi rides are down 23 percent this year compared to 2015, according to data obtained by DNAinfo Chicago, continuing an overall trend beginning in 2014, when UberX was introduced in the city.

Perhaps that’s why the Top Cabbie competition, announced a month before City Council declined to apply the same regulations to Uber and Lyft as taxi companies have assented to for decades, rang a little hollow to those who work in the industry.

“I think it’s great that there’s acknowledgement [of] great cab drivers out there. I think it’s wonderful,” says George Lutfallah, longtime publisher of the monthly cabbie-oriented newspaper the Chicago Dispatcher and a member of the city panel that sifted through Top Cabbie nominations. However, he adds, “There is this disconnect between doing these positive things for taxi drivers and sort of ignoring the other [things]. Are other issues not being addressed? Yes, that’s true.”

In the 1930s, as detailed in The Taxicab: An Urban Transportation Survivor, people became fed up with various failings of the private market—breaking-down cars, fare wars, drunk taxi drivers, and the like. At the urging of the higher-ups of the taxi industry, many municipal governments, including Chicago’s, began passing stringent taxi industry regulations, the most substantial of which was the requirement of a taxi medallion, or license, to operate a cab. The regulation allowed local governments to control the quality, safety, and quantity of taxi services, essentially classifying them as public utilities.

Despite its intent, Chicago’s medallion system was easily taken advantage of; by the 1980s, just two companies had control of the majority of the city’s medallions, allowing them to exploit their drivers and keep prices inflated. Now, though most of the city’s approximately 7,000 medallions are owned by these large corporations and outside firms that buy hundreds of medallions and then lease them out, nearly a third of medallions are owned by drivers like Farkye who own four or less, according to data provided by CDU.

Advertisement

It’s hard to argue that this monopolistic system was perfect, but the entry of competitors like Uber and Lyft has disrupted a delicate balance in the industry—solving a problem for consumers, but not for drivers caught in the middle.

There's no official number of drivers for ride-hailing apps in Chicago, but most estimates put the number at around 90,000, compared to about 12,000 licensed city cab drivers. Ride-hailing app drivers are free from many of the fees, taxes, and other requirements cab drivers are saddled with—including the lease or mortgage payments on the medallion, ground transportation taxes, and a one-day training course and test at Harold Washington College.

Because of the decreased barriers to competition, “It’s that much harder to find fares, in order to squeeze out a living driving a cab when the underlying asset—the medallion itself—is falling in value. It’s reflective of an industry that’s either in crisis or that is shrinking,” says Robert Bruno, director of the University of Illinois’ Labor Education Program and lead author of a comprehensive 2008 study of the city’s drivers, which was affiliated with a now-defunct cab drivers’ union.

“There’s been a ratcheting down of the workplace conditions,” he says. “We’ve actually degraded the ability of people to earn a living driving a cab in the city.”

This spring, the fight made it to City Council in the form of an ordinance regulating ride-hailing endorsed by CDU and sponsored by Transportation Committee chairman Ald. Anthony Beale (9th). The proposal would require Uber and Lyft drivers to obtain restricted chauffeur’s licenses (the same license limo driver are required to get); require ride-hailing companies to have at least five percent of their fleet be handicapped-accessible, the same as small cab companies (though just 2.7 percent of all city cabs are wheelchair-accessible); cap the age limit of eligible vehicles at six years; reinstate a program providing financial incentives for cabbies to service underserved areas outside of the Loop and Near North Side; and, most controversially, require ride-hailing drivers to take drug, fingerprint, and background checks, which taxi and limo drivers are all required to do.

Uber and Lyft were unsurprisingly not supportive of Beale’s original ordinance, which made it through committee and prompted a chaotic vote in the full chamber. "This … forces part-time Lyft drivers into an onerous, outdated model — requiring hundreds of dollars in fees just to share a seat in their car," said a Lyft spokesperson. "Hurting one industry to help another is the wrong approach,” agreed Uber.

Advertisement

The clout involved in the fight, particularly from Uber’s side of the ring, was substantial. Uber’s lawyer was Michael Kasper, Michael Madigan’s top legal deputy and the lawyer who represented Emanuel in his successful 2011 court battle to prove his residency. The company was particularly opposed to the fingerprinting requirement; former attorney general Eric Holder, whose law firm advises Uber, wrote a letter to Beale denouncing fingerprint checks as racially discriminatory. Not to mention that Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s brother, Hollywood agent Ari, is an Uber investor.

Both companies threatened to pull out of the city, as they did this year in Austin, Texas. By the time the final ordinance passed in late June, reportedly pushed through at the last minute by Emanuel over the objections of aldermen who said they did not have enough time to fully analyze the rules, its only major changes were a new licensing category for ride-hailing app drivers, a commitment by the city to study the fingerprinting issue, and a commitment by ride-hailing companies to study wheelchair-accessible vehicles.

(Unsatisfied with the latter compromise, local disability rights group Access Living sued Uber this week, accusing them of violating the Americans With Disabilities Act and only providing 14 wheelchair-accessible rides between 2011 and 2015. This August, Lutfallah wrote in the Dispatcher about prohibitively long wait times or completely unavailability for Uber and Lyft rides for people with disabilities.)

As the Tribune reported, “Ald. John Arena (45th) said the watered-down rules will lead toward a ‘Wal-Mart economy’ in Chicago, where ‘everything is cheaper, but you're not safer.’”

The city’s Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection, which launched the Top Cabbie competition and is charged with regulating the taxi industry, has made some changes as it tries to adjust to the reality of the market. Last month it introduced some reforms to the regulatory system, making it more difficult for police officers to issue seemingly arbitrary tickets, a practice nearly half of the drivers surveyed by Bruno found to be unfair. CDU put out a rare release that praised the BACP, but again called for equitable regulations between cab drivers and ridesharing companies.

And, in an effort to help cab drivers compete with Uber and Lyft, the city last year commissioned two taxi-hailing apps, Arro and Curb, which theoretically would be required for all city cabs. However, Cometas Dilanjian says the heavily-advertised apps are not available to everyone yet. As president of City Service Taxi Association, which has over 400 vehicles under its banner, Dilanjian says they have not been able to use the apps yet, because Arro and Curb keep saying they are "tweaking" them. The BACP denied a FOIA request for usage data about these apps, saying that they constitute a "trade secret," so it's impossible to say how well the apps are truly working for drivers.

Even a fare increase passed by the city in December is a “double sword,” as Farkye refers to it. “From the North Side to O’Hare airport was 30, 35 dollars. Now you can go for 40, 45. Maybe a total of seven to eight dollars more. But on the other side, if the riders can get an Uber ride to the airport for 20 dollars, why wouldn’t they take an Uber than go with a taxi driver?”

When asked if the BACP has any position on how ride-hailing companies have affected the day-to-day financial lives of the city’s cab drivers, spokeswoman Mika Stambaugh says, “The City of Chicago is focused on expanding and improving safe and reliable transit options for residents.”

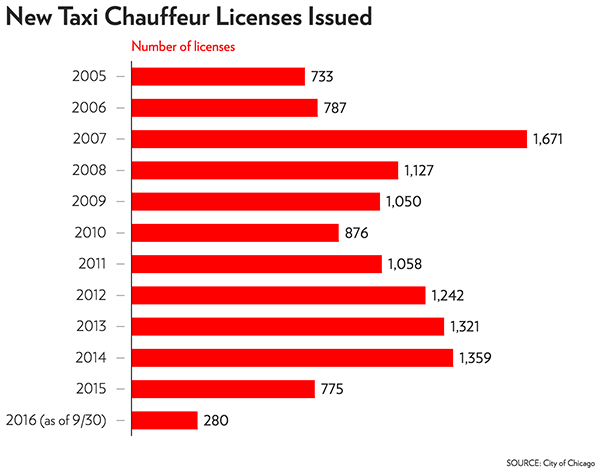

However, there’s no doubt the industry is rapidly contracting; according to data released by the BACP in response to a FOIA request, the amount of new taxi drivers obtaining city licenses has dropped steeply over the past three years; there are just 263 new drivers on the road as of August—73 percent less than the same time period in 2014. Additionally, between 2002 and 2014, the city averaged 44 taxi medallions surrendered or foreclosed on a year; since 2014 when UberX entered the market, the city has averaged 89, with 141 given up in 2016 alone.

“At this point, I would not recommend anybody to drive a cab,” says Elias Lopera, a CDU member who has driven a city cab for over two decades ever since emigrating from Colombia. “They’re not gonna get pickups. They’re not gonna make a living. I’m not going to recommend something that is not profitable at all.”

Lopera owns two cabs and corresponding medallions, one of which he drives and another that he leases out to other drivers. Recently, though, he says he’s had difficulty finding anyone to drive the cab, which sits unused in his garage. “It’s been hard to find drivers at this point, [but] I still have to pay the lease and insurance and all the taxes,” he says. Dilanjian notes that “probably 90 percent” of the 400 drivers affiliated with his company are six figures in debt from purchasing multiple medallions to expand their businesses during better economic times.

And though the city increased taxi fares some 15 percent last winter, recently introduced rebates for small fees for new drivers, and reduced some fees and fines, the economic climate for drivers is so drastically different for cab drivers due to ride-hailing that more sweeping reforms are required, according to Bruno, the labor researcher.

Earlier this year, Ald. Raymond Lopez (15th) proposed an ordinance that would require the city to determine a fair price for medallions and buy them back from owners to help them “recoup some of their losses,” but never actually filed the legislation. His spokeswoman, Joanna Klonsky, says in an email that Lopez has “raised the idea in discussion with his colleagues and the [Emanuel] administration, but an ordinance along these lines has not been introduced to date.”

Advertisement

Compounding the situation further is a revamping of the city’s taxi regulations Emanuel and the BACP undertook in 2012, which increased lease rates and city fines while capping the amount of hours drivers can work and vehicle mileage limits.

There have been attempts by drivers to bring about reforms through the courts, most notably a lawsuit by driver Melissa Callahan that made the case that the city’s onerous regulations on cab drivers should require them to be considered city employees. Both a district and appeals court have found in favor of the city, and the Supreme Court decided earlier this month to not hear her case, effectively ending her suit.

Just last week, a federal appeals court dealt a blow to a separate lawsuit brought by the taxi industry group Illinois Transportation Trade Association, that called for the city to regulate ride-hailing app companies as it does taxis. Though a lower court ruled that the lawsuit could proceed, federal judge Richard Posner reversed the decision, writing that ride-hailing and taxi companies are as different as “cats and dogs.” According to Dilanjian, a vice president of the ITTA, the industry group is “reeling” and is considering whether or not to make an appeal to the Supreme Court.

Cab drivers interviewed for this story say they know of a lot of colleagues who ditched cab driving for Uber, but the numbers there are even murkier, especially when it comes to income. Uber says Chicago drivers earn an average of $16 an hour, but their accounting is regularly called into question. Taxi earnings are hard to nail down as well: Bruno’s 2008 study found cab drivers make around $12,000 a year, but the city commissioned a study in 2014 finding that cab drivers make over $33,000 a year. Pro bono research conducted for the city in 2011 by an environmental consulting firm came to just over $19,000 a year. (That research was not released publicly; it was provided to Callahan in response to a FOIA request and later obtained by Chicago.) Additionally, many of the regulations imposed on taxi drivers provide benefits, like workers’ compensation, that Uber and Lyft do not provide.

“In the long-term situation, I’m just hoping for some reason the city will change their minds and will think cabs are needed in Chicago,” says Lopera. “That’s what I’m [hoping will] happen, but I’m just trying to hang in there until then. Hope is the last thing you lose, and that is what I have right now.… At this point, I would like to run and stay away from this business, but because of those two medallions, I cannot run.

“[I’ll] hope that something happens, [that] someone with common sense will come and say, ‘this is wrong what is happening right now.’”