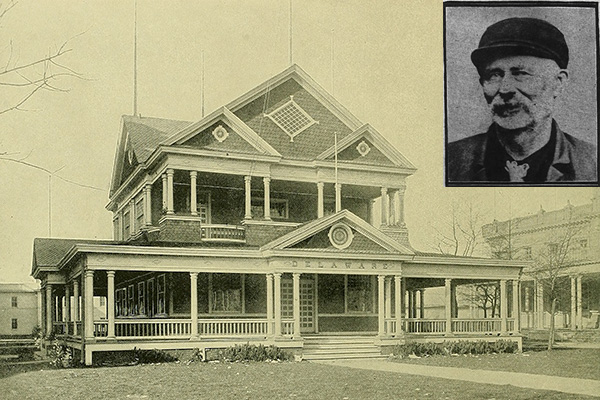

On March 12, 1904, Cook County Deputy Sheriff John Long traveled to the banks of Wolf Lake, which straddles the Indiana border, to serve Ellis Bennett an eviction notice. Long’s men hauled Bennett's furniture out into the mud, while Bennett locked himself in a bedroom with several firearms, warning that he would send to heaven anyone who tried to remove him from the hunting lodge that had been his home for the past decade—a building that had housed the Delaware exhibition during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Bennett, a grizzled frontiersman, was not going easily.

How Bennett had come to live in the Delaware House some 11 miles from its original World’s Fair site—on land he did not hold title to—is a strange tale.

In 1869, the Canadian-born Bennett and his young family arrived in the vast marshland around the Calumet River, an area the Chicago Tribune would later describe as a “solitary waste,” where “human life is only possible by the blessing of copious horns of whisky.” At the time, the shallow Wolf Lake was receding, perhaps due to logging and the diversion of water along the Calumet watershed. It was on this new hunting ground Bennett would make a living as a duck hunting guide.

Although he came off as a rough-hewn, charming eccentric in the press, Bennett was not the sort of Canadian that you would want as a neighbor. In 1873, he torched a widow’s shanty to initiate his own claim to her land. Four years later, a court ordered Bennett to compensate her. According to the Chicago Inter Ocean, Bennett had such trouble with house fires that people in the region joked that he was operating a lighthouse. After his fourth house burned down, Bennett took up the extraordinary opportunity to buy the Delaware House from the World’s Fair.

Constructed entirely out of wood imported from Delaware at the cost of $7,500, the 18-room Southern Colonial-style building was described by one guide as small, though “handsomely built,” just like the First State itself. The economic depression that followed the World’s Columbian Exposition had killed hopes to have the building taken apart and reconstructed in Delaware. Facing the threat of demolition, Bennett bought it for a mere $400 in June 1894.

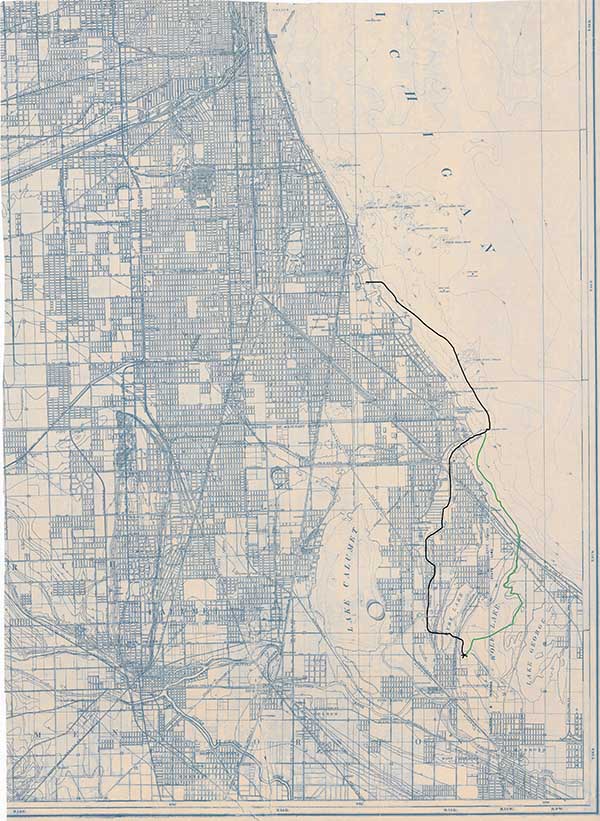

He had the house put on rollers and hauled to two scows in Lake Michigan, which floated along the lakeshore and down the Calumet River. Finally, the house was dragged to dry ground at Wolf Lake.

(Based on newspaper accounts, the map below depicts two possible routes the Delaware House could have taken to Wolf Lake.)

He wasn't alone there. Knickerbocker Ice Company held a competing claim to the land, and though it was an unloved company, Chicago had a voracious need for ice.

By 1890, the city was consuming an estimated 2 million tons of ice a year. Artificial refrigeration was not yet economically viable, and the stockyards of Chicago depended on slabs of ice harvested from Wisconsin and Illinois lakes to keep meat from rotting while being shipped by rail. “Besides that used in the homes, hotels, saloons, cafes, butcher shops, packing houses, by steamboats and railroads, in dining cars and trains,” the Chicago Herald noted, interests from “New Orleans, the West Indies, Mexico and Central and South America all bought here.”

Knickerbocker claimed to have the largest ice houses in the world. During the winter months, hundreds of seasonal workers labored around the clock, sawing one-foot thick slabs of ice from the lake. The company claimed that its product was pristine, but chemists from the reform-minded Civic Federation discovered that it was as pure as one would expect coming from a weedy lake home to enormous flocks of ducks. They also had a reputation for buying out or underselling competitors in the spring, then raising prices in the summer.

In 1895, Bennett filed an unsuccessful suit against Knickerbocker, claiming the company thugs had roughed him up, stolen his pillows and blankets, and framed him. In the past, the legal complexities of sorting out land ownership on a reclaimed lakebed, combined with Bennett’s willingness to defend by force his dubious stake to a marsh, seemed to have protected Bennett from eviction. Eventually, Bennett’s arguments about “squatter sovereignty” cut no ice with the court. Deputy Sheriff Long brought 25 men with him to evict Bennett, who held out in his windowless bedroom for 36 hours.

In the early morning of the siege, Bennett shot twice through the bedroom door after Long knocked. Hearing snoring around noon, Long broke through the door with an ax. Bennett’s act of defiance made national news. “The hull [sic] thing was gigantic bluff, an’ I didn’t try to hit nobody,” Bennett told the Inter-Ocean from the Cook County Jail a week later.

Bennett not only faced a challenge from the Knickerbocker Ice Company, but also from John Jaman, a house mover who claimed the Delaware House through an unpaid promissory note. Bennett had apparently stiffed the company that had transported the Delaware House to Wolf Lake in the first place.

Mysteriously, Bennett was able to move back to Delaware House. Court records give no guidance as to how Bennett came to a settlement with either Knickerbocker or Jaman.

Yet the ornery, deadbeat pioneer did not hold on until his death. In 1915, Bennett was shot in the groin by one of his sons after he ordered the younger man to move out of Delaware House. In 1922, Bennett returned to his hometown in Canada to marry for the fourth time. He died in Seattle in 1931.

Reminiscing about the grand house by Wolf Lake where the Bennetts reportedly served muskrat to guests like Anton Cermak, the Chicago Tribune noted in 1943 that the Delaware House stood as a crumbling ruin “among the trees Bennett planted around it ‘to prove it’s mine.’” According to the Southeast Chicago Historical Society, the house came down in the '50s. Unlike his contemporary, unscrupulous squatter George Streeter (for whom Streeterville was named), there is no monument to Bennett; his kingdom has been taken over by industry, a quiet neighborhood, and parkland. Despite it all, the ducks still come back, the most stubborn holdouts of them all.