The other day a guy yelled at my wife for crossing at a crosswalk. It's on a racetrack stretch of street where cars generally won't stop even if you're partway into a street with a bus pulling up, so I wasn't surprised, but I was still cross about it.

Then I thought for a minute: wait, it's a transverse crosswalk on a relatively high-speed, de facto four-lane street. Of course no one stopped. Transverse crosswalks don't work very well.

When trying to explain why anyone does anything on a street, a good rule is to look at the infrastructure. Bad drive behavior, bad cyclist behavior, bad pedestrian behavior: look at the infrastructure.

One bad behavior that's been noted recently is that drivers infrequently stop for pedestrians in Chicago. And one way to look at it is this: "Many Drivers Ignore Crosswalk Law: Study."

It's kind of an unfortunate headline; the story, by the Trib's Jon Hilkevitch, points out that the new Active Transportation Alliance study (which is somewhat informal), found that the city's recent attempts to increase the number of drivers who stop for pedestrians at crosswalks is actually working:

| Number of trials | Initial compliance | Partial compliance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmarked crosswalks | 88 | 4 | 12 |

| Common marked (painted) crosswalks | 84 | 15 | 13 |

| Marked crosswalks with other safety features (bricks, raised, in-street signage, parkway signage, flashing beacons) | 36 | 22 | 4 |

(Initial compliance means the first car stops; partial compliance means that at least one car in the wave of traffic stops.)

So that's pretty good, an increase from 18 to 61 percent compliance moving from a regular painted crosswalk to a crosswalk with additional features.

The ATA study didn't distinguish between types of common marked crosswalks. But it's entirely plausible that some drivers barely saw the crosswalks, if they're transverse crosswalks, like the one that got my wife yelled at:

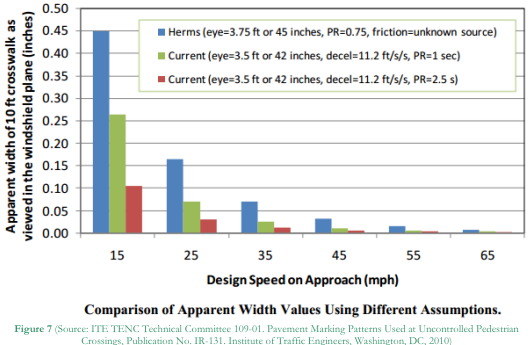

Transverse lines are particularly difficult for motorists to see, and for this reason, many agencies are beginning to change crosswalk markings to patterns that provide greater visibility. In 2010, the ITE Traffic Engineering Council Committee analyzed a 1970 study by Bruce Herms that looked at the apparent width of a crosswalk as viewed from an approaching vehicle. Using current standards for motorist eye height and perception-reaction time, the committee determined that transverse crosswalks were “essentially not visible” because the apparent width of a 10 foot crosswalk was often below a quarter inch when viewed in the windshield pane.

At 35 to 45 miles per hour—typical for where my wife was crossing—the width of the crosswalk is virtually indistinguishable from zero.

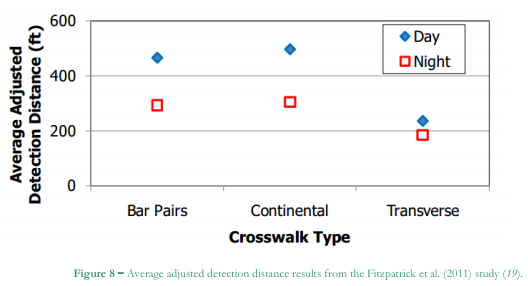

Another recent study looked at the distance at which different types of crosswalks became visible:

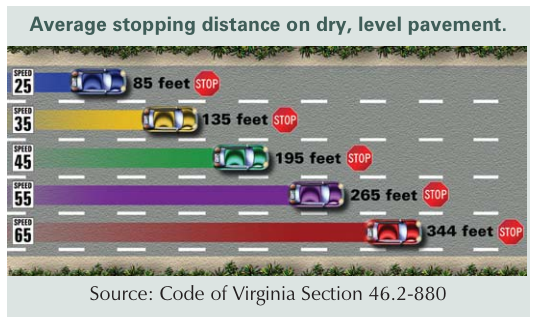

Compare that to average stopping distances (via; inclusive of recognition, response, and actual braking distance):

At 45 miles per hour, a driver has virtually no leeway to stop after noticing a transverse crosswalk; at 35, a little more than a second. The big, thick bar pairs, running parallel to the street, become visible at a much greater distance.

Pedestrian cones—basically like the spring-loaded signs you've probably seen popping up around the city—have been found to increase stopping further still, and are particularly cost-effective. Even cheaper, if kind of sad, are flags that pedestrians can wave to indicate that they're crossing and wish not to get run down. (There's an ever-more elaborate range of elaborate crossing devices like beacons and overhead signs, but there's simply not much money, particularly at the federal level, for pedestrian infrastructure.)

So look both ways when you're crossing the street in Chicago. And look down, too: the design under your feet makes a difference.