So, nice weather we're having. It's actually official: as summer ended yesterday, the Chicago summer came in with below-average temperatures, notably in the often miserable month of July, which finished at 3.6 degrees below average.

And by one especially important measure, it was one of the nicest summers on record: "Summer ended Monday with only three days at or above 90 degrees, the fewest since 2004. This is only the 10th time in 143 years that there have been three or fewer, according to the National Weather Service."

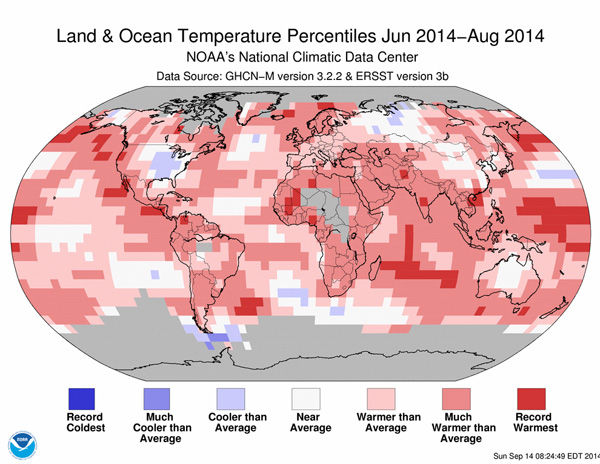

How lucky were we? The center of the country—basically the Midwest, the Southern Appalachians, and the Gulf—was practically the only place on earth that was cooler than average from June through August, with the exception of one swath of Siberia and comparatively small parts of central Russia and Alaska.

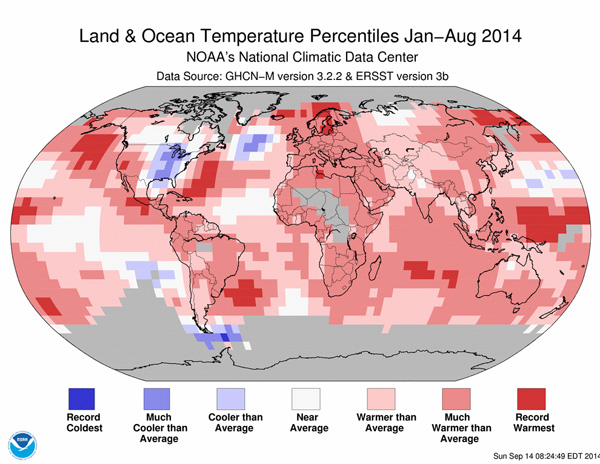

Expand the timeframe from January to August of this year, and the corridor along the Mississippi has been the only place on earth with much-cooler-than-average temperatures.

Worldwide, it's been one of the warmest years on record so far. And it's been warm pretty much everywhere but here. It's been a very strange year: cool weather over the Midwest, while California figuratively and literally burns:

Even among these years, 2014 is unprecedented: never before has the country experienced such large areas of simultaneous, opposing temperature extremes in the same January-July period. At a combined 40% of the country, the area affected by extremes so far this year is nearly double the size you’d expect due to chance.

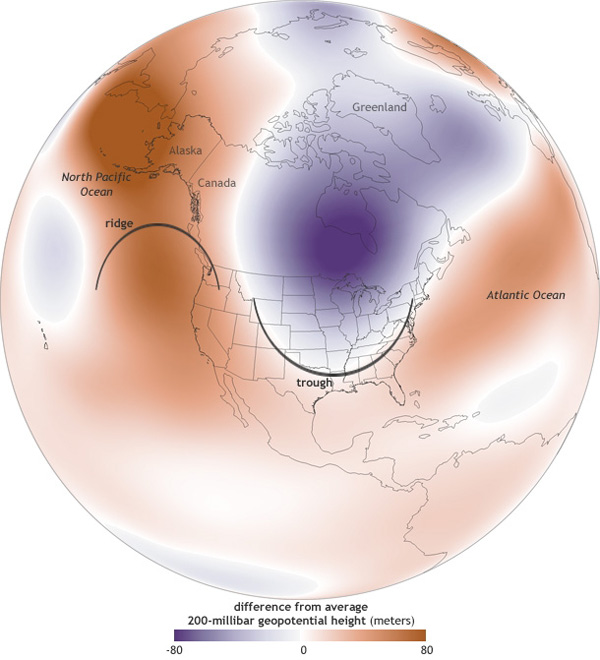

And the two are related. The "ridiculously resilient ridge" behind California's immense drought is the flipside of a ridiculously resilient trough that's aimed arctic air directly at Chicago. Here's what it looks like for our long period of cool weather from November through July:

Translation: "The polar jet stream repeatedly followed a path of steep ridges and troughs over North America during this period; the unusual configuration occurred frequently enough that it left a permanent impression on the average pressure patterns during the period."

No one's sure why; meteorologists are even arguing about whether or not to call it a "polar vortex." But one thing is clear, as Eric Holthaus writes: "the first five months of 2014 were collectively the fifth warmest such period globally since records began. This winter was a temporary cold blip in a small corner of the Earth. We just happen to live there."