As Rick Perlstein reflected in my Q&A with him, an immense part of Barack Obama's appeal as a candidate was his promise to bridge a politically polarized nation. It was the subject of the DNC speech in 2004 that all but created his national profile and provided its legendary climax, as Chicago's David Bernstein wrote in 2007:

The momentum built when Obama proclaimed: “Tonight, there is not a liberal America and a conservative America; there is the United States of America. There is not a black America and a white America and Latino America and Asian America; there’s the United States of America.” Then the speech climaxed with the edited red-state, blue-state assertion. Even Obama was caught up in the moment. “I remember standing behind him and watching his feet move,” recalls Stephanie Cutter, Kerry’s former campaign press secretary. “It was like he was dancing at the podium. His feet were moving to the rhythm of the speech.”

So, yeah, that didn't work. A decade later, polarization is considerably worse. "The White House no longer believes Obama can bridge divides," Ezra Klein recently and convincingly wrote. "They believe — with good reason — that he widens them."

What's going on? Checking a theory of Clarence Page led me towards an interesting answer. He recently offered several thoughtful reasons for the current polarization of the country, one of which should be familiar:

Tribal media. That's what I call the fragmentation of media in the age of cable TV news, AM talk radio, social networks (Twitter, Facebook, etc.) and targeted marketing like Amazon's chained book recommendations ("If you liked … then you might like …") that are tailored to the narrowest of tastes. Endangered is the refreshing and often-enlightening serendipity of running into unexpected ideas, people or experiences that one might encounter while browsing through a newspaper or bookstore. (Remember those?) Instead, it's easier to slip into an information silo of news and views that reinforce what we already believe, correctly or not.

Having been involved with online media for a long time, it's an assertion I hear regularly. And one, admittedly, I can be quite skeptical of—as a fairly hardcore user of social networks and the fragmented conversation of media that's proliferated outside the traditional gatekeepers of old, I stumble across "unexpected ideas, people, or experiences" all the time. Siloing is obviously easier in the age of the self- and algorithm-driven newsfeed, but the panopoly of voices stands in contrast to the editor-curated feed of the newspaper. (Twitter users, FWIW, are worried about changes to the service that could make it less

Poking around, I discovered that political scientists do in fact believe that the massive expansion of media outlets that essentially occured in my lifetime has polarized the public. Cable television in particular. But the how is unexpected.

Last year, Princeton's Markus Prior published an immense literature review on how the media drives political polarization (or doesn't); it's as good a review of the current thinking as I've ever seen. He writes, regarding his own research (emphasis mine):

Compared to print media, broadcast television helped less educated viewers learn more about politics. Even people with little interest in news and politics watched network newscasts because they were glued to the set and there were no real alternatives to news in many markets during the dinner hour. News exposure motivated some of these less educated, less interested viewers to go to the polls. And because their political views were not particularly ideological or partisan, their votes reduced the aggregate impact of party ID, so elections were less partisan in the broadcast era.

If the goal was to find a connection between media and more partisan elections, we can stop looking. The culprit turns out to be not Fox News, but ESPN, HBO, and other early cable channels that lured moderates away from the news—and away from the polls.

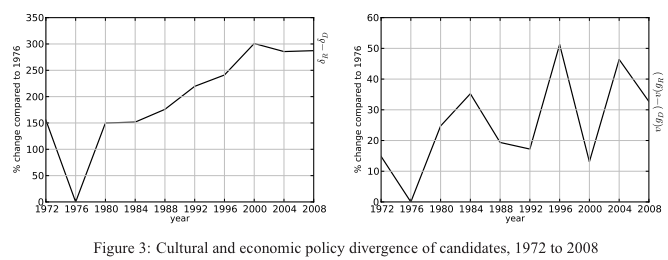

This timeline syncs up with the recent findings of two University of Illinois profs, Stefan Krasa and Mattias Polborn, on the polarization of political candidates as explained by voter preference. They find that since 1972, the 1976 election was the least polarized, and polarization has increased steadily since—mostly attributable to cultural polarization.

Obviously, there are other causes than "cable television." Rick Perlstein's work, in particular his most recent book, is particularly good on this account—1976 was a very strange year. The Republican Party was breaking apart at the seams in the wake of Watergate, but the Democratic party was also abandoning (and being abandoned by) the New Deal coalition as future Reagan Democrats began their split from the party. Jimmy Carter, mythos aside, was a conservative Southern Democrat; young political star Gary Hart led the charge of the "Watergate babies" against the old progressive coalition.

Arguably, it's something of an outlier. But the pattern is nonetheless clear. Partisan media outlets stepped into this growing divide, and if political scientists are not sold on the idea that Fox News and its ilk are particularly responsible for it, they did find an engaged audience at the ends of the political spectrum.

The evidence suggests that the media may contribute to polarization, but in a more circumscribed way than many commentators suggest. Take first the question, of choice, and in particular, whether people seek out media choices that reinforce their existing beliefs. The answer is (perhaps not surprisingly) yes: Republicans are more likely to tune in to Fox News and liberals are more likely to watch MSNBC. Researchers have also found that these effects are stronger for those who are more partisan and politically involved.

[snip]

But what about the effects of partisan media on those who do watch these programs? While this research tradition is still relatively young, scholars have found a number of effects: on vote choice, participation , and attitudes toward bipartisanship and compromise, among others. The research looking at effects on attitudes finds that while there are effects, they are concentrated primarily among those who are already extreme. This suggests that these programs contribute to polarization not by shifting the center of the ideological distribution, but rather by lengthening the tails (i.e., moving the polarized even further away from the center).

Another thing Perlstein said to me in the interview: he recalled, from his 1970s childhood, "whenever those old white men were on your television set for half an hour every night, you could just expect to be sad." Shortly thereafter, you could banish those old white men and their sad news from your television—and the silent majority did.