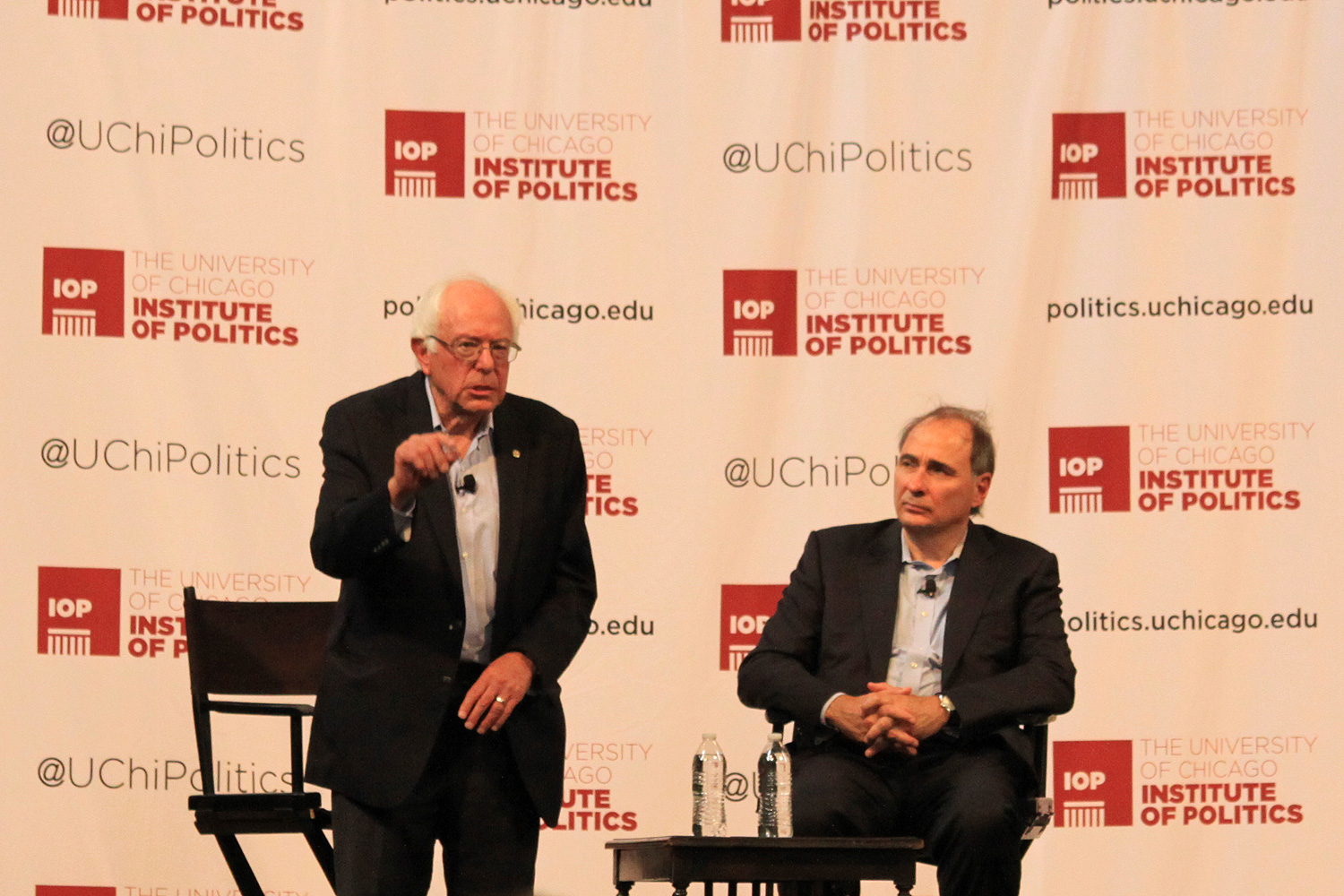

Bernie Sanders began his talk today at the University of Chicago, his alma mater, like so many other candidates—with a story of his modest upbringing. In Rockefeller Chapel, introduced by another alumnus who made good in politics, Institute of Politics director David Axelrod, Sanders might have dwelt on the opportunities it gave him—the place where he led the school's first civil-rights sit-in, the place where, he said, "I learned here about democratic socialism."

But he had another story.

"I also think about what is something of a painful, difficult memory—of coming here as a young man from a family that did not have a lot of money, a family whose mom and dad did not go to college, and suddenly interacting with a whole lot of young people whose families did have money, whose families were often professional," Sanders said. "I would be less than honest if I didn't tell you that that transition was a difficult one."

En route from Des Moines, doing his job as a presidential candidate, to Washington, DC, to do his job as a senator, Sanders stopped in Chicago to speak to a full house at the university's immense chapel. Following from his reminiscence of his student days, Sanders focused on a message of reengineering government to provide opportunity.

That reengineering would begin with the highest court in the land, and that opportunity would extend to presidential candidates…candidates like Bernie Sanders.

"I am often asked by media and others, 'well, Bernie, you touch on a number of issues, which is the most important issue'? There is one issue that is unique, because it impacts every other issue. And let me be as blunt in telling you what many of you already know. And that is, as a result of the disastrous Supreme Court decision in the Citizens United case, the American political system has been totally corrupted," Sanders said in defending publicly funded elections.

"When you have a situation, which is what we have today, where one family, the second-wealthiest family in America, the Koch brothers, are spending $900 million in this election cycle, that is more money than the Democratic party is spending and the Republican party is spending. When you have one family, an extreme right-wing family, that spends more money than either of the two major political parties, my friends, you are not looking at democracy, you are looking at oligarchy.

"I have not made many campaign promises so far. But one promise I have made that I reiterate to you today: no nominee of mine to the Supreme Court will get that job unless he or she is loud and clear that one of their first orders of business will be to overturn Citizens United."

Sanders made a few more campaign promises, focusing on somewhat modest gains in economic and workplace protections: guaranteeing 12 weeks parental and medical leave; raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour; eliminating the $250,000 cap on Social Security contributions, and using it to increase benefits by $65 a month.

As a candidate, Sanders has cut away at what was once a substantial polling disadvantage to Hillary Clinton, and has surpassed Clinton in recent Iowa and New Hampshire polls. He's struggled with support from black voters, and activists have, in the words of Salim Muwakkil, "forced Sanders to readjust his policy platform and stump speeches, which now include diatribes against institutional racism and the criminalization of the black community."

Today Sanders mentioned the inequalities of the criminal-justice system. But he brought it back around to economic inequality as well.

"We've got 5.5 million young people hanging out on street corners all over America, without jobs and not being in school," Sanders said. "If anyone here thinks there is not a correlation between that fact, and the fact that we have so many people in jail, you would be mistaken. In my view, it makes a hell of a lot more sense for us to be investing in education and jobs, than in jails and incarceration."

Many have also wondered if Sanders could translate his unusual political resume—mayor of the small, homogenous city of Burlington and independent senator from the small, homogenous state of Vermont—to nationally elected office. One questioner broached this topic politely: Could Sanders, well-known for his regard for constituents, care for a country?

"To be very honest with you, I know my own state, and I know what I do in my own state," Sanders said. "But the United States is a bit bigger than the state of Vermont. You raise an issue that I hope we all think about, and that is—I'm influenced by what Pope Francis has recently said—how do we care for each other?

"What you're asking for is a cultural revolution. And I believe in that. And it's not easy. I think what you're talking about is to create a nation—and it's pretty radical stuff—in which we actually care about each other, rather than looking at the world as, I'm in it for myself, and to hell with everybody else. So there's a lot of work to be done, and I don't have all of the answers, but clearly it will involve millions of people at every level."

Axelrod ended the questioning there. After asking millions of people for help in changing the government, Sanders had to fly back to Washington to cast a vote to just not shut it down.