A little more than eight years ago, when we were casting about at Chicago for a feature story to accompany a “sex and love” package, I suggested a piece on Playboy’s halcyon days in the city where it all began.

That was the ’60s and early ’70s, when the original Playboy mansion at 1340 North State Street served as “both the epicenter of a new sexual freedom and an object of scorn,” as I wrote at the time.

More concretely, it was the setting for some of the most notorious, celebrity-filled parties of its time. … Where else might you see Frank Sinatra chuckling at a gorgeous naked woman diving into an indoor pool filled with other gorgeous naked women? Meet Joe DiMaggio and Dean Martin and Warren Beatty and the Rolling Stones in the same ballroom? Slide down a fireman’s pole to an underwater bar lit by the sparkling green of an aquarium window through which yet more gorgeous women could be seen cavorting like so many mermaids?

In those days, Playboy boasted a circulation of seven million—a number nearly impossible to fathom today (last year its print circulation was just over 670,000) and had its name on a theater, the original Playboy Club (on Walton), the late-night TV show Playboy After Dark (originally taped at 190 North State Street, now home to ABC7’s studios), and, most visibly, atop the Palmolive Building in an illuminated sign that would rival the monstrosity, at least in size, that currently scars the Trump Tower. Then there was the Playboy Club in Lake Geneva, one of the first adult resorts.

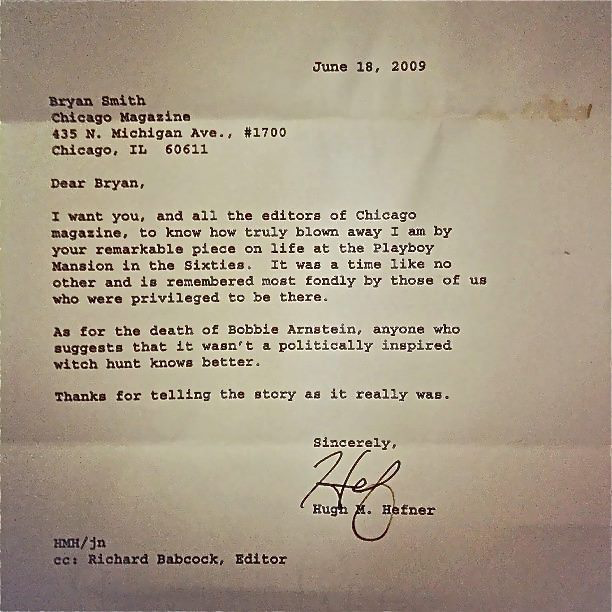

To do the story justice, however, meant talking to the man who famously started it all on a card table in an apartment in Hyde Park with $8,000 he raised through hawking his furniture and borrowing from family and friends: Hugh Marston Hefner. And that meant a trip to the far better known mansion near Beverly Hills, to which Hefner decamped after being cleared in a federal drug investigation.

I wanted him to walk me through that time—when Playboy bunnies could be seen riding horses through Lincoln Park and Hefner’s “Big Bunny” jet sat parked at O’Hare.

And so it was that I arrived one afternoon at a gate at the bottom of a hill that wound up to the mansion featured in so many movies and TV series, to meet a man who by then, in 2009, was a legend.

I parked my rental next to Bentleys and a Rolls Royce parked in the curving driveway and was led into the iconic dwelling. Because it was the afternoon of a weekday, the place was utterly quiet—not a cavorter of any kind, male or female, to be seen. I was walked past Hef’s movie room, one of his favorite places, where he watched first-run features with every celebrity imaginable. It was dark and gloomy and rather rundown, I thought with a pang of wistfulness.

I was told to wait at the opening to a hallway that led to the mansion’s library, where Hef and I would chat for a good two hours, a room that featured a large framed oil painting of Hefner in his signature red smoking jacket with the black collar, pipe held rakishly to his cheek.

I waited. And waited. And then … there he was. He appeared out of the gloom like an apparition, robed, sure enough, in the same smoking jacket in the painting.

We were led into the library/parlor, where I recorded my impressions:

He sits on a plum-striped couch in the library, a dim parlor that features a bare-breasted ceramic bust of Barbi Benton, one of Hefner’s enduring loves and the woman partly responsible for his leaving Chicago for good in 1975.

He is 83 now, his hair thinned and woven with white. He is hard of hearing in the right ear, so I am asked to sit to his left. He wears his trademark crimson smoking jacket draped, as always, over silk pajamas, which today are black. He discarded his pipe many years ago, on his doctor’s advice, after a mild stroke in 1985. But that missing piece of stagecraft, deployed in the fifties to make himself look sophisticated, hasn’t diminished the image, the bearing, the great natural charisma, the reality of who he is. He is talking about the L.A. mansion, telling me, as he does all interviewers, that it is his spiritual home. Moving here, he explains, was the best thing he’s ever done.

Still, as he speaks, his voice conveys wistfulness, and he concedes that he looks back to those years in Chicago fondly. Seeing him so at ease in the lap of his current luxury, it’s hard to imagine he would long for the grit of the Windy City, particularly given the painful chain of events that sealed his desire to leave. But so powerful were those days, those memories, that the King of Fantasy, in this late afternoon of his life, admits he would love to turn back the clock, if only for a moment. ‘What I would love to do,’ he says, his voice taking on a curious poignancy, ‘would be to get in a time machine and simply walk back into that mansion in 1965.’

And so we did, metaphorically, at least. I had heard about his intellect and sharpness, even at his advanced age. Still, I marveled at his ability to recall in detail his Chicago days, the great parties at the State Street manse.

When we were through, he bid me goodbye and an attractive publicist gave me a tour of the grounds—the “woo grotto,” just as I’d seen it in so many documentaries and feature films, the game room filled with Playboy pinball machines. I was hoping to see at least some wild life. What I saw instead, was wildlife—peacocks that roamed the grounds, spreading their tails in agitated splendor, huge zoo-worthy enclosures in which monkeys swung through branches past chattering birds of all colors.

There were no leggy blondes, no stray centerfolds stretched on the chaises that sat empty in the backyard. But truly, it was fine by me. I was wonderstruck enough.

And today, on hearing the news of Hefner’s death, I’m wistful yet again. I know, I know. But still. Still. He was Hef.