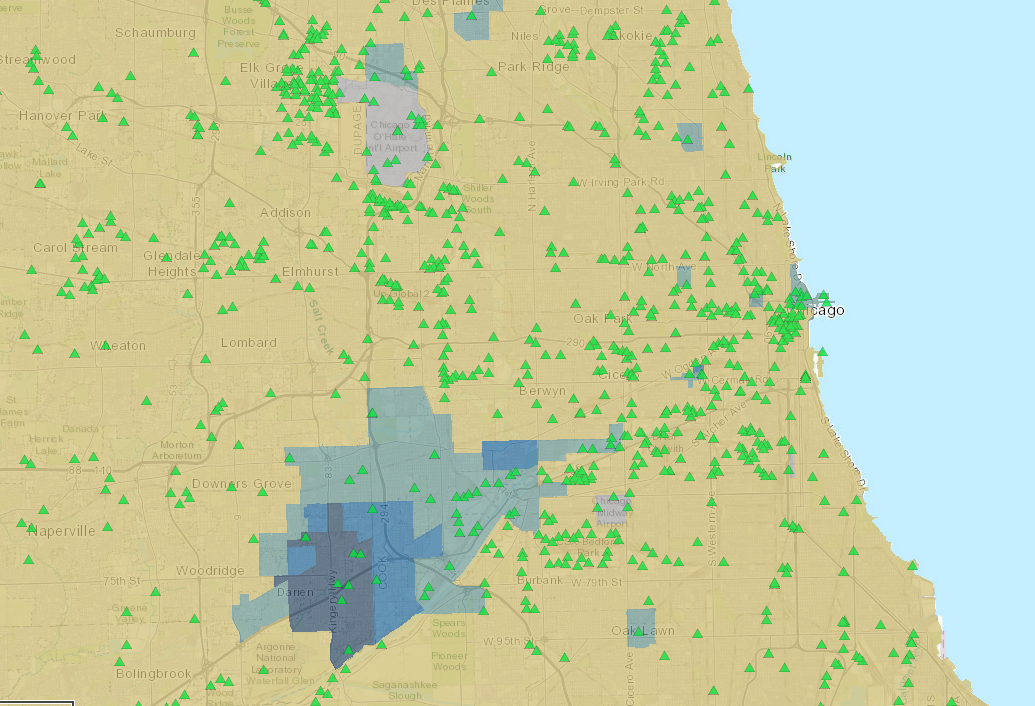

If you call up the 2014 National Air Toxins Assessment map, which estimates the risk of cancer for residents of every census tract in the United States, and type in “Chicago, IL,” you’ll see a dark patch of blue over the southwest suburb of Willowbrook:

That’s the location of Sterigenics International, a company that uses ethylene oxide to sterilize medical products like surgical trays and gowns. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, exposure to the gas can “result in respiratory irritation and lung injury, headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, and cyanosis. Chronic exposure has been associated with the occurrence of cancer, reproductive effects, mutagenic changes, neurotoxicity, and sensitization.”

Indeed, according to the NATA map, residents of Willowbrook had a cancer risk of 300 in a million, specifically as a result of exposure to ethylene oxide emitted by Sterigenics. That’s the highest score anywhere in the Chicago area, and ten times higher than the vast majority of census tracts, which ran a risk of 30 in a million.

In fact, I searched the entire map of the United States, and the only place I found that exceeded Willowbrook’s cancer risk was St. John the Baptist, Louisiana, in the state’s notorious “cancer alley” of oil refineries and petrochemical processors.

Sterigenics operates two facilities in Willowbrook. Both have recently been the site of protests, with residents wearing surgical masks and carrying signs reading “Stop Sterigenics! Say No to Ethylene Oxide Sterlization in Our Community!”

Sterigenics secured a new permit from the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency in May 2015. But since then, the federal EPA changed its assessment of ethylene oxide from “probably carcinogenic to humans” to “carcinogenic to humans,” concluding that the cancer risk of inhaling the gas is 30 times higher than normal. State Sen. John Curran, who represents the Sterigenics facilities, joined the protests, and has filed legislation to re-examine the company’s permit, which doesn’t come up for review until 2020.

A spokesperson for Sterigenics recently told the Tribune that improvements made to the plant in July had reduced ethylene oxide emissions by 90 percent. At an August 29 public meeting attended by hundreds of Willowbrook residents, Sterigenics officials assured the community that the facility has “continuous monitors to measure ethylene oxide concentrations.”

Meanwhile, Gov. Bruce Rauner, whose former private equity firm GTCR owns Sterigenics, declared the situation “not a public health immediate crisis.”

“[The] company took the actions themselves [and] put in control equipment to reduce the emissions,” Rauner said.

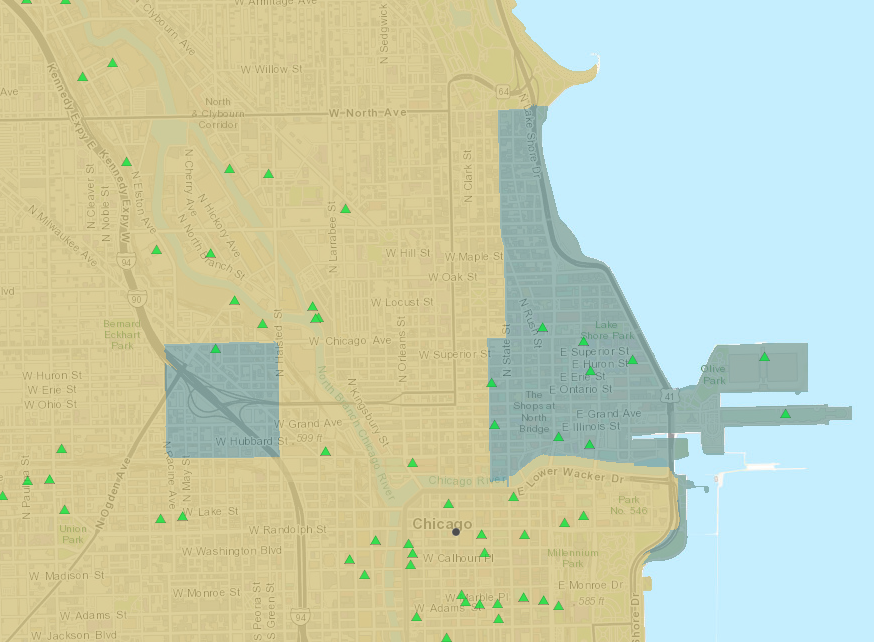

Beyond Willowbrook, the NATA map shows a number of spots in the Chicago area where cancer risk was higher than surrounding areas — in some cases as a result of ethylene oxide emissions — though still within the EPA's acceptable risk range:

- Near Douglas Park, on the Southwest Side of Chicago, the risk was between 70 or 80 per million.

- Just north of O’Hare Airport, the risk was 70 per million.

- The risk was 50 per million in a portion of Des Plaines near Lutheran General Hospital, which was emitting ethylene oxide.

- In North Chicago, home to Medline Industries, which also deals in medical equipment, the risk was between 100 and 200 per million.

- In Lyons, an industrial area, the risk was 90 per million, also attributed to ethylene oxide.

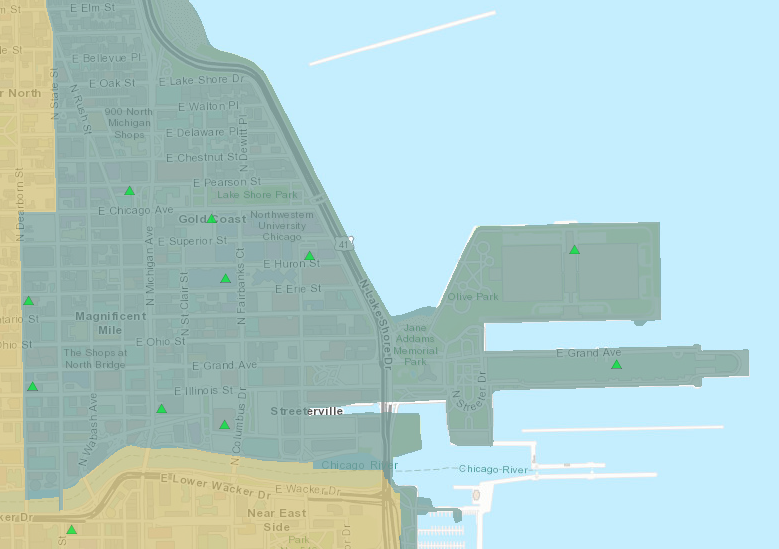

- And most notably, in heavily populated, touristy Streeterville, the risk was 50 or 60 per million.

According to the NATA map, airborne toxins in Streeterville are attributable to a number of sources, primarily cars but also office buildings and facilities such as hospitals. The map data shows that Northwestern Memorial Hospital was emitting ethylene oxide, formaldehyde, and hexane (a noncarcinogenic toxin), and that the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital was emitting formaldehyde and hexane — but both at levels that are permissible and that the EPA doesn’t consider cause for concern.

Meanwhile, someone on Navy Pier was emitting trace amounts of toluene, a solvent used to make paint, paint thinner, nail polish, and adhesives. The site claims it was coming from “Rocky’s Restaurant,” but there's no such eatery there. There was, however, once a Rocky’s Bait Shop in the area, which served fish and shrimp before Navy Pier became a tourist attraction.

Other Streeterville institutions contributing to the slightly elevated cancer risk are the WMAQ tower, whose most significant emission is benzene, and the Tribune Tower, which emitted acetaldehyde, a compound “widely used in the manufacture of acetic acid, perfumes, dyes and drugs, as a flavoring agent and as an intermediate in the metabolism of alcohol.” (Reporters drink a lot, so the Tribune’s move to Prudential Center may have relocated that threat.)

In the cases of Willowbrook, North Chicago, and Lyons, NATA cautioned that “[r]isks in this tract from ethylene oxide are based on 2014 emissions data, which may have changed since 2014.”

Still, one resident who attended the Willowbrook meeting didn’t want any ethylene oxide, at any level.

“I think I speak for the majority of people here. We want you out! Goodbye,” the resident told a Sterigenics representative, according to WGN. “We don’t want you in our community. Shame on you putting a place like you run in our community around four schools and a daycare. Cheers.”