My father sat on the front step of the farm house and threw grounders. First, one at a sharp angle to the left, then the next one to the right, putting me through my paces. I was the second baseman on my Little League team and had dreams of playing baseball professionally. Behind me the vastness of the East-Central Illinois prairie unfolded its horizon that was only interrupted by the occasional grain elevator or dairy barn. But for me the real drama existed solely in that yard, where I never wanted to let a ball get past me. And the whole time in my head I repeated, “Do it just like Ryno.”

Dad was a Cubs loyalist in a family of Cardinal fans. He took over his role as a farmer after his own father, and in a lot of ways lived a life similar to him, so he had to rebel in some way and chose baseball. Dad cut his teeth as a farmer in the early days of having radios in tractors, or more accurately, on them: There weren’t even cabs to ride inside of, just a radio bolted above one of the back wheels. One of the only channels that came through consistently was WGN, so Dad listened to Jack Brickhouse give the call and fell in love with the Cubs. He passed this passion on to my older brother and I. We grew especially fanatical when Mark Grace joined the team, as we imagined that we must be related somehow, and weren’t above lying to our friends that this was indeed the case. But even given the possible familial connection with Grace, Ryne Sandberg was my favorite player.

For most kids that don’t go on to play professionally, as I resoundingly did not, sports are a way to learn about life. One of the reasons that Ryno became my favorite was because Dad would use him as an example for me to follow. It wasn’t any technical part of his game — his steady footwork in the field even when making virtuoso plays — or his smooth, unbothered swing; it had more to do with his temperament. He was stoic regardless of the situation. He had the same expression if he flashed some dark arts glovework or if he struck out and couldn’t move the man from second to third with no one out. Even during the infamous “Sandberg Game” on June 23, 1984, when he single-handedly stole the soul of Cardinals reliever Bruce Sutter with two home runs, he dutifully jogged at a brisk pace around the bases without cracking a smile. “That’s how you do it,” Dad would say. “Never get too high and never get too low.”

Although Dad probably wouldn’t have put this in these terms himself, there was something Zen in this approach. Lao Tzu in the classical Taoist text Tao Te Ching preaches this same kind of emotional equilibrium, famously stating that “Mastering others is strength; mastering yourself is true power.” Ryno had that power, and had his own way of expressing it in his 2005 Hall of Fame speech: “Make a great play, act like you’ve done it before. Get a big hit, look for the third base coach, and get ready to run the bases. Hit a home run, put your head down, drop the bat, run around the bases. Because the name on the front is more — a lot more — important than the name on the back.” Act like you’ve done it before. Coming as we did from a family that did not run short on Midwestern repression, this sounded like a commandment tailormade for us. Keep your mind away from the far ends of the emotional spectrum and show respect. Or as Lao Tzu put it, “To the mind that is still, the whole universe surrenders.”

My father was evangelical about this sort of head-down stoicism. But our family equilibrium was rocked when my father passed away in 2004 in an accident in our machine shed on the farm. The family was devastated in the ways you would expect. I was 25 but still felt like a kid in a lot of ways, and Dad’s absence was a visceral emptiness I carried for years afterward. In terms of the Cubs, he was one of the many that didn’t get to experience the Cubs winning the World Series in 2016. He was one of those who didn’t make it.

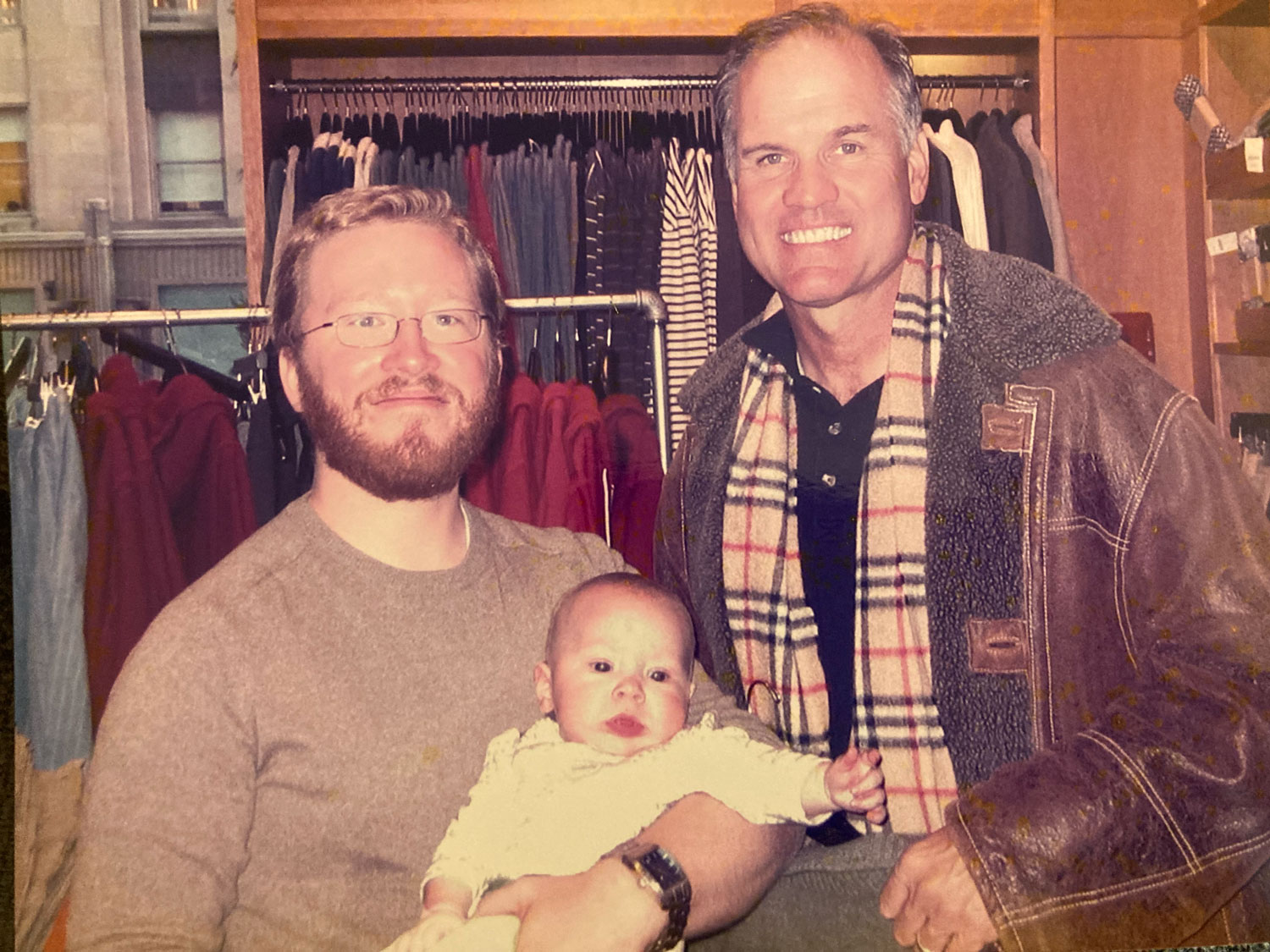

In 2008, four years after my father’s passing, I had a chance encounter with Ryno at the J. Crew at the Water Tower mall in downtown Chicago. It was our first trip to the city with our first daughter, visiting my brother who after the farm became a longtime Chicagoan. I felt my brother’s hand grip my arm with surprising urgency; I thought something was wrong. “Look,” he hissed in my ear. “It’s Ryno!” Sandberg was languidly perusing the flannels, and had an armful of clothes to try on. I didn’t plan anything to say before rushing up to him — and it showed. I stuttered my way through a litany of effusive praise that he bore with elegant patience. At that time he was the manager of the Cubs’ Class-A team, the Peoria Chiefs, and I remember throwing in a “Go Chiefs” in my firehose of flattery, which seems especially embarrassing now.

He let me come to an awkward end before responding, “Thanks. Who’s this?” and pointing to my infant daughter, who I had kind of forgotten I was carrying in my arms. He asked her name, what stage she was in as far as crawling, sleeping through the night, etc. To his enormous credit, he was far more interested in her than he was in me. We chatted for a few minutes as Lily squirmed, staying still for long enough to take a picture with Ryno. I was buzzing afterward. I was glad to have had the chance to tell him what he meant to me as a kid, but he showed me what he was more interested in than adoration, which was family. It’s a startling irony of my life that Ryne Sandberg got to meet my daughter and my father never did.

The next time I shared a space with Ryno was Game 7 of the World Series on November 2, 2016, in Cleveland. My brother and I were in the left field bleachers for the excruciating emotional odyssey that was the deciding championship game. I had strayed very far from Lao Tzu that night, as I got too high, too low, and everything in between. I didn’t see Sandberg that night, but read later that he was there as a team ambassador. When it was all over, I found myself reaching both of my arms up to the sky. My brother hugged me from behind. Sports can be called the most important least important thing, but if I’ve ever felt my father’s presence move toward me, even a single inch, it was when the Cubs finally won the World Series.

Whenever I saw Sandberg on television in the years after my father’s death, I had a similar, if not as intense, feeling of Dad being with me, that he was still telling me that I should be watching Ryno and doing what he did. Seeing him keep his trademark even keel throughout his battle with cancer — from the triumphant announcement that he was in remission last August to his upbeat message in what were to be his last days — is a clinic on how to cherish life. In his last words to his fans, he struck a balance of resilience and satisfaction, both “continuing to fight” but also “making the most of every day with my loving family.” Even in death, he acted like he’d been there before.