For a Chicago Cubs fan, history is little more than a collection of teachable moments. Take the 1929 World Series, when centerfielder Hack Wilson misplayed two routine flies, costing his club not only the game but the championship. Manager Joe McCarthy defended his star, saying, “What do you want? He lost the ball in the sun. He didn’t put the sun up there.” Or take the black cat, which made a mystifying appearance at Shea Stadium in Queens, New York, on September 9, 1969, as Cubs third baseman Ron Santo stood on deck, portending an infuriating late-season Cubs collapse. Or take the Bartman ball (please!), wherein a goofy fan reached for a foul that might otherwise have been caught by outfielder Moises Alou and then, amazingly, was blamed for the debacle that followed.

But to me, a fanatic who can almost remember Ernie Banks, no moment has had more to teach — not just about the game but about life — than the legendary clubhouse meltdown by team manager Lee Elia, who died a month ago, on July 9, with the Cubs in first and playing better than they have since 2016, the year they finally broke the 108-year curse. Known to Chicago faithful simply as The Rant, Elia’s tirade has had more to teach us than a course on philosophy.

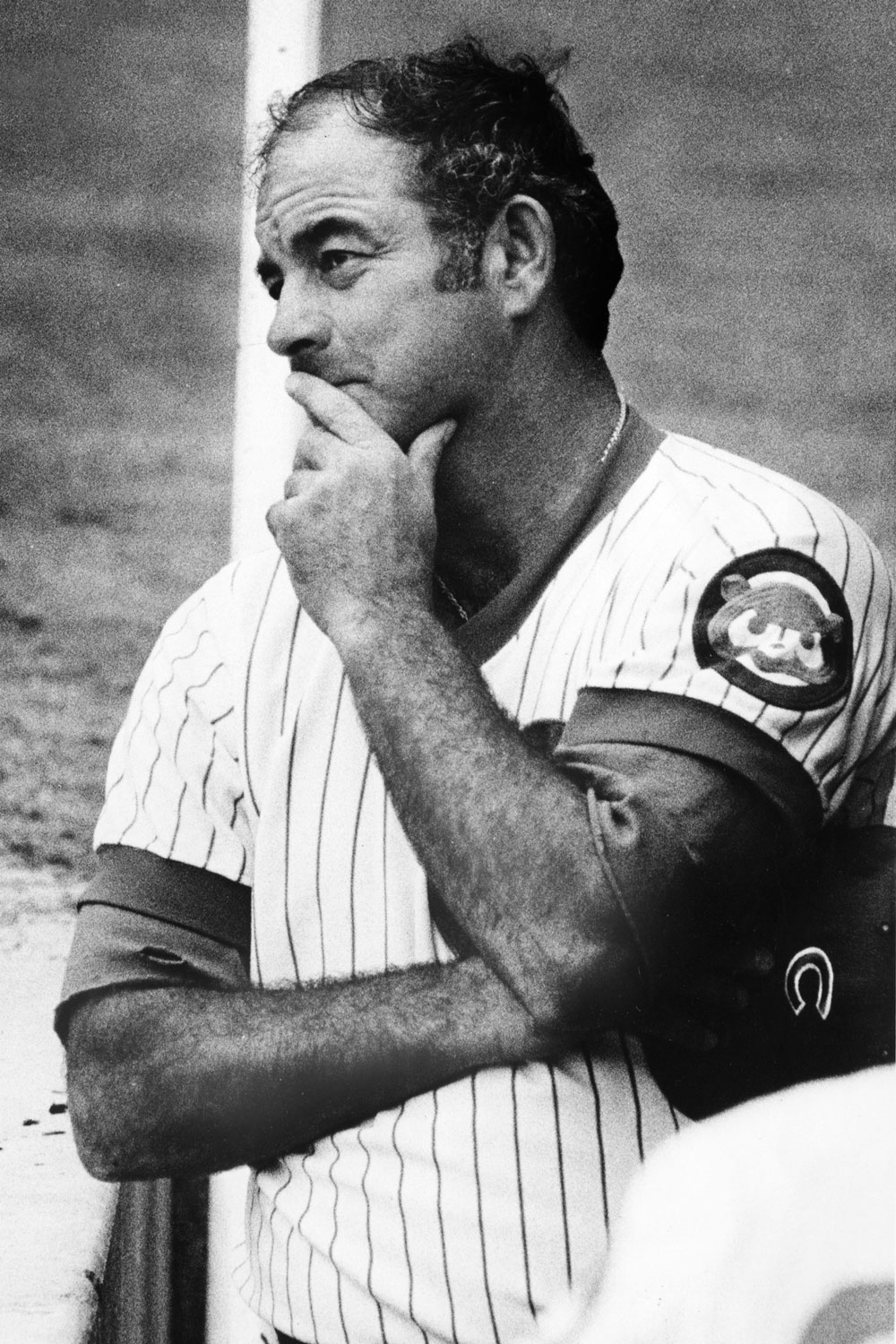

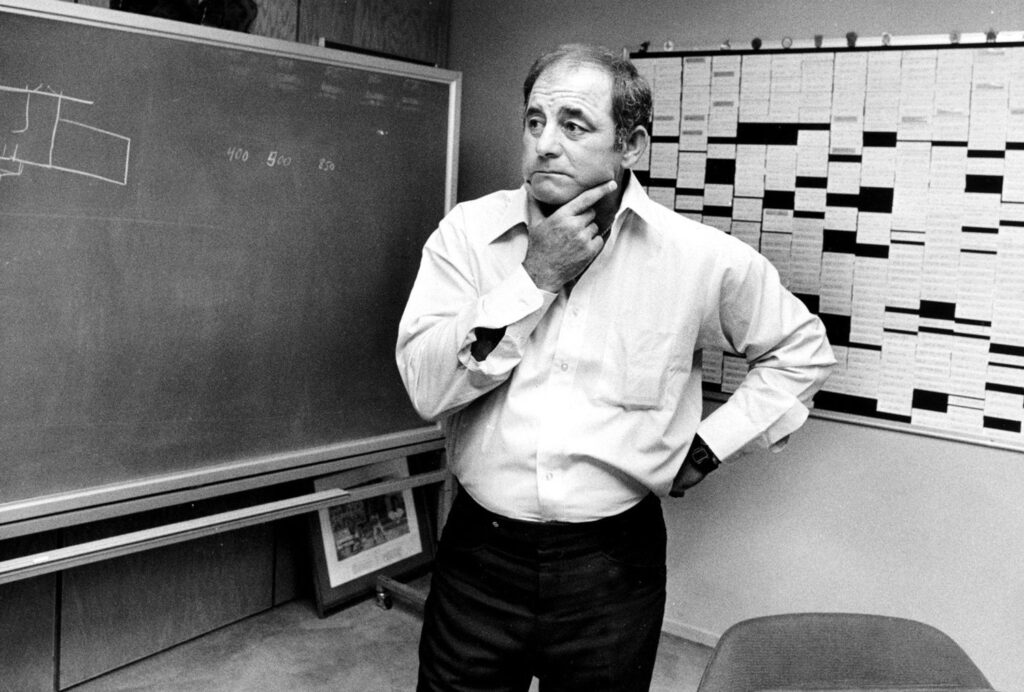

I was 14 on April 29, 1983, when Lee Elia started his second season in charge of the Cubs. That day, 9,391 people turned up at Wrigley Field — a pittance of hardcore lifers whom Elia would call “fuckin’ nickel/dime people.” These being the days before lights at Wrigley, the game began early, 2:45 p.m., in a blustery 17-mile-an-hour wind. The Cubs lost a heartbreaker to the Dodgers, dropping their record to 5–14. En route to the leftfield gate, shortstop Larry Bowa and outfielder Keith Moreland were set upon by boozy fans, doused first with garbage, then with beer. Elia was right behind. Furious by the time he reached the clubhouse, he called a handful of beat reporters into his office.

It was a single comment that set him off: “Tough way to lose a game, huh?”

The Chicago Tribune characterized what followed as “a three-minute tirade peppered with more than 50 profane words including 30 F-bombs.” But those are just stats. They tell you about as much about The Rant as the 48 home runs and 130 strikeouts in 1980 tell you about slugger Dave Kingman, who was tall, mustachioed, mean, and lived on a houseboat. To truly appreciate The Rant, which was as lyrical in its way as James Joyce and as discursive as David Foster Wallace, you must approach it less as a sports fan than as a literary critic.

The first lines served as an overture, a soliloquy that summed up an entire worldview: If those are “the real Chicago fuckin’ fans, they can kiss my fuckin’ ass, right Downtown, and print it! They’re really, really behind you around here. My fuckin’ ass!”

It was less the manager’s anger that amazed us than his style, the energy and verve, the dazzling swear-to-non-swear ratio. The Rant electrified me and my friends the same as the first paragraphs of Catcher in the Rye, or the voiceover in Goodfellas. It was like eavesdropping on the grown-up world, a nighttime landscape of poker tables, pool halls, and Rush Street taverns. Here was an adult portion. Here, finally, was the truth. The message and the message behind the message were all about demystification. In just three minutes, Elia called into question nearly everything we’d been told about our city and our team.

Since grade school, we’d been told that Cubs fans were the best in baseball: We packed the stands in good years and bad, we’d been the first rooters in the MLB to throw enemy home runs back onto the field, rejected like a dog rejects a heartworm pill. Here was Elia saying that we were not the best fans and possibly even the worst: nickel/dime people who come out to boo. “We’ve got guys bustin’ their fuckin’ asses and those fuckin’ people boo … and that’s the Cubs?” he’d said. “My fuckin’ ass! They talk about the great fuckin’ support that the players get around here, I haven’t seen it this fuckin’ year.”

We’d been told that ownership’s devotion to day baseball was about purity — proof that Wrigley was the last real temple of the national game, as orthodox as the Catholic liturgy before Vatican II. Here was Elia saying that the result of all that day baseball were seats filled with the weird and unemployable. “The motherfuckers don’t even work! That’s why they’re out at the fuckin’ game! Eighty-five percent of the fuckin’ world is working” and “the other 15 percent come out here.”

We’d been told that professional athletes play for the love of sport, that Ted Williams worked so hard because he wanted people to look at him and say, “There goes the best hitter that ever lived,” that Shoeless Joe Jackson, a banned member of the dreaded 1919 Black Sox, would’ve played the game for free. But now here was Lee Elia saying it was not love but hate that motivated him, a desire for revenge against his own team’s fans. “I’ll tell you one fuckin’ thing: I hope we get fuckin’ hotter than shit just to stuff it up them three thousand fuckin’ people that show up every fuckin’ day.”

The manager apologized the next day, but it was too late. He had told us what he really thought, and the most honest of us knew that he was right, that we were lowdown, nickel/dime, fair-weather front-runners. We felt bad about ourselves every time he took the field, and so he had to go.

He managed his last Cubs game — a win against the Reds — four months later, on August 22, 1983. But I will never stop appreciating him. For the profanity, for the poetry, and for the true motivation of The Rant. He was defending his players. Stick by the boys, stand up for the team — that’s what Elia was doing at Wrigley Field that day. Forget the city, forget the scoreboard, forget the fans — play like it’s us against the entire world. You do that, nothing else matters.