The City News Bureau of Chicago was the starting point for several of America’s most celebrated journalists: Mike Royko, Seymour Hersh, and Pam Zekman among others. The local wire service closed in 2005 after operating around the clock for 115 years. Stories about CNB have taken on characteristics of epic fishing tales, a mixture of fact and fiction: The bureau broke stories on the St. Valentine’s Day massacre (true), the Tylenol murders (also true), and on Pearl Harbor (not verifiable); one of its reporters committed armed robberies in order to write stories about them (unlikely); and its reporters would get yelled at by gruff editors until they cried (exaggerated).

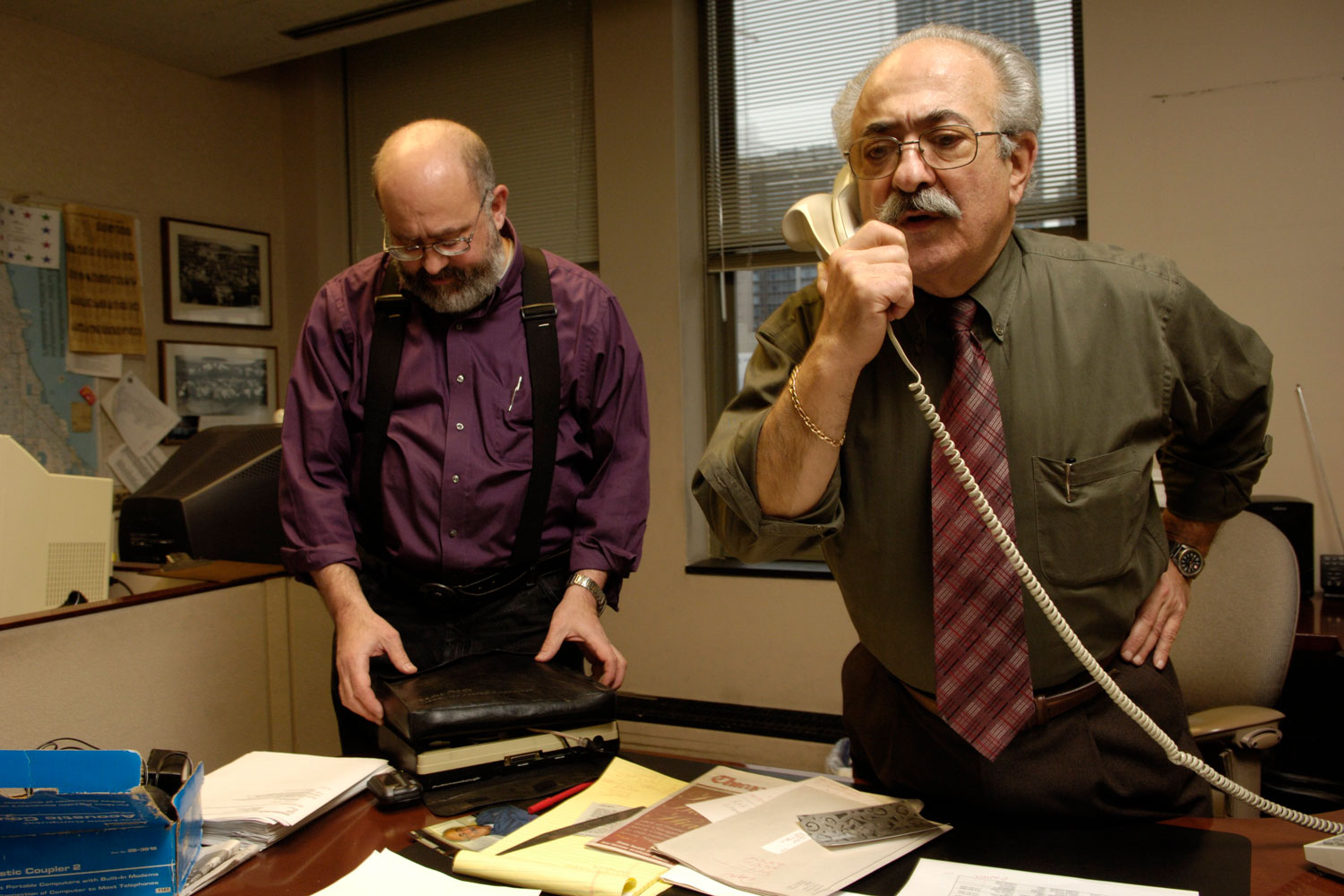

To set the record straight and to tell the real history of CNB, two former staffers have produced Sirens in the Loop: A History of the City News Bureau of Chicago, publishing February 1. The book was a passion project of Paul Zimbrakos, the legendary managing editor who worked at CNB from 1958 until its closing. Zimbrakos passed away in 2022 before finishing the book, but his friend and former employee James Elsener picked up and finished the project.

Elsener, who worked at CNB from 1970 to 1972, stayed friends with his former boss, often having lunch with Zimbrakos while Elsener worked for the Chicago Tribune, The Business Ledger, and the Daily Herald, where he retired in 2017.

Elsener says he wasn’t aware that Zimbrakos was working on a book until around 2019, when they had lunch with another former CNB alum, journalist Gary Washburn.

“Gary asked Paul if he ever thought of writing a book and he said, ‘Yeah, I have been’ and told us the story,” Elsener says.

A few months before he passed, Zimbrakos asked Elsener to be part of the project, and Elsener would inherit three large containers of notes, pictures, and stories about CNB. In 2024, he set about finishing the book.

“It was more of an editing and organization job than a writing job,” Elsener says. Along the way, he received help from CNB veterans Wayne Klatt, Bob Saigh, and Anne Hennessy. Klatt worked more than 40 years as CNB’s assistant city editor and thought up the title of the book, as a nod to the fact that CNB would send out bulletins to customers whenever sirens in the Loop were heard.

For those unaware, the brief history is this: City News Bureau was founded by the newspapers of Chicago in 1890, serving as a wire service for the papers, television, and radio stations in town. The bureau was famous for long hours, low pay, and turning aspiring reporters into tough veterans in short order by covering crime, coroner cases, and a series of hard-news beats such as courts, city hall, and education. CNB editors would notoriously send reporters back to the scene of a crime to confirm the smallest detail. As the bureau’s mantra went: “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.”

Reporters would then call their info in to “rewrite” men and women who would turn their words into a story, which was disseminated to CNB’s clients. This model worked for more than 100 years — from the days when literal copy was sent through pneumatic tubes under the city streets to the computer age — until the wire service failed to increase its prices as costs rose. In 1999, the TV and radio stations of Chicago unanimously balked at the service doubling its fees, but the Chicago Tribune came to a last-minute agreement to keep CNB going with a smaller staff, still led by Zimbrakos, and renamed City News Service. By 2005, the curtain would finally come down on the service for good.

Elsener, who worked at CNB more than 50 years ago — making $120 a week, including an extra $10 a week for his previous service in the Marine Corps — says the most surprising thing he discovered was how hard Zimbrakos worked to keep CNB open in 1999. Zimbrakos approached numerous entities to purchase the bureau: a company out of Los Angeles called City News Service, the MacArthur Foundation, and other individual investors. He even tried calling on Columbia College and Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, all to no avail.

That same year, Zimbrakos asked CNB alums to send in stories and memories of their time at the company, which ultimately landed in Sirens.

“Fifty years after I worked there, so much of it came back, especially reading the comments and memories that people sent,” Elsener says.

The book is divided into 23 chapters, including sections on the history of the bureau, Zimbrakos’ story, the various beats, notable alumni, and the fight to save CNB. The book highlights some of the major stories that CNB reporters covered: the Our Lady of the Angels fire in 1958, the 1979 crash of American Airlines flight 191, and the Tylenol poisoning murders of 1982. A chapter called “Lore Galore” addresses the many exaggerated stories about the famed outfit.

Among the misconceptions about CNB was that young reporters would be routinely yelled at by editors, like recruits being dressed down by drill sergeants in the military. Elsener explained that while that may have been the case in the early days of the wire service, Zimbrakos had a different approach, often using guilt more than anger to motivate him.

“He’d say my name with two syllables, ‘Ji-im, you’re one of my better guys. This shouldn’t happen this way,’ ” Elsener recalls. Zimbrakos would also remind his young staff that they were “professional reporters” to build their confidence, rather than attempting to motivate them with negativity.

“It really was a great lesson in leadership and how to handle people,” Elsener says.