T

he sight is improbable enough to bring a passerby to a full stop and entrancing enough to keep him there, gazing skyward as long curtains in a sheer sun-yellow fabric flutter and twirl gracefully in a soft breeze. Suspended from a rooftop cable that spans the U-shaped courtyard of a new three-story burnished-block house in Old Town, these balletic sentinels shimmer across from a reflective entrance of glass and steel.

“I’ve always wanted to have outdoor curtains-as they did in Roman times, as they do in Venice at the Piazza San Marco,” says Rodrigo del Canto, the designer and owner of the house and the managing principal of the Chicago firm Macondo Corp Architects & Planners. “This is the equivalent of having the sea in front of you because the curtains move and they dance with the wind and they’re really beautiful.” (On buffeting days, to prevent them from sailing onto the roof of the house, they are tied just above their ground-level hems or secured to a fence or the columns flanking the courtyard; in the winter, they are removed and stored.)

Producing this visual reverie seems natural for an architect who named his firm Macondo after the fictional town in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the acclaimed novel by the Colombian Nobel Prize winner, Gabriel García Márquez. Originally from Chile, del Canto earned degrees in engineering, architecture, and urban design and planning in the United States and in Europe before moving to Chicago in 1977. After working for several small firms and serving as the deputy commissioner of economic development for the City of Chicago during the administration of Mayor Harold Washington, he founded his own firm in 1991.

|

At this point, del Canto believes, his profession would benefit from a touch of the magical realism that informs García Már- quez’s work. “Architecture is so complex today-the legal and the financial requirements you have to comply with,” del Canto says. “We have lost the enchantment of architecture, and few are able to exercise their minds truly the way it was meant to be.”

In 2004, he aspired to that in the design for his new house. Previously he had renovated a three-flat and a noodle factory in Lincoln Park and was then living in a town- house while deciding what he would rehab next. Now single, he has three children from previous marriages: a son, Tristan, 32, an ethnomusicologist who lives in Austin, Texas, and two daughters in Chicago, Isabel, 14, and Catalina, 18, who divide their time between their father’s place and their mother’s. Initally, del Canto had not planned to build, but a broker found land not far from Cabrini-Green that he could not resist-a 30-by-125-foot vacant lot situated on a block of Chicago Housing Authority buildings and relatively new condominiums and single-family houses. The properties were well kept, del Canto says, and his feeling was that they would stay that way.

Finding a lot that was five feet wider than the norm was an unexpected gift, but the site still presented challenges. To the south was a two-flat owned by the CHA, meaning that the brightest exposure was blocked. To the north was a vacant lot owned and cultivated as a garden by a couple who lived in the next house. “I had a fixed property to deal with and an unknown one,” del Canto says, explaining that he had to assume the lot might eventually be sold. His solution was to orient his house to the north, with a walkway leading from the street to the entrance. Even if a house were built next door, the courtyard would continue to provide openness and light.

|

|

The curtains reined in on a windy day. |

The concept for the design was simple: two separate towers-one principally for del Canto, the other for his daughters. On the first floor, a grated metal bridge is suspended between the two towers, linking the living room on the east with the kitchen and dining area on the west. “The connection is delicate,” del Canto explains, “which to some degree is what happens with your children. They grow and fly away.” An open metal stairway winds at right angles from the first floor to the third, floating free from a glass-block wall on the north that offers both illumination and privacy. Beneath the stairs is a lily pond-a more fluid, elemental connection spanning the length of the bridge on the ground floor.

In addition to the kitchen and the dining area, one tower comprises a study, the garage, the master bedroom and bath, a guest room, and two decks. Above the living room in the other tower are the bedrooms and baths of Isabel and Catalina, a family room with a small kitchen, a laundry room, and another deck.

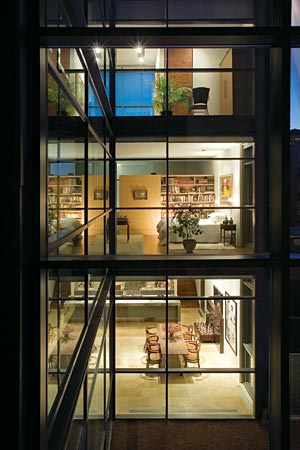

The layout is logical and well ordered; but animated by the architecture and the transparency of the space, the simple becomes visually sensational. In the central U-shape of the entrance, all three floors are planes of glass framed in steel, providing a voyeuristic view from one tower into the other. “As I circulate through the house, I’m always looking at other parts of it because it’s all glass,” del Canto says. “I am inside, and I am outside. I have the ability to experience the house objectively, but as soon as I connect to another portion of the space, that part becomes subjective.” The level of engagement and detachment is much more complicated and provocative than it is in a domestic world with standard boundaries and solid walls.

|

|

A view looking into the living room shows the connecting links between the towers: bridge, lily pond, stairs, and glass-block wall. |

Del Canto is also drawn to intense color-especially yellow. “It’s a way to bring the sunlight in,” he says. “I think of it as paradise.” But here, after consulting with his brother Gonzalo del Canto, a furniture designer in Concord, Ontario, and two Chicago-area interior designers, Maria Schmidt and Marcia Weese, he decided that a more neutral palette should prevail. “The idea was to let the forms speak for themselves,” says Schmidt, who has worked with del Canto on two previous projects. For the main floor and the common areas upstairs, they selected an off-white with a tint of blue and orange. “Very light-it gives it a little bit of warmth,” del Canto explains. “It could have been a cool color with the gray of the steel.” He chose a richly textured Jerusalem limestone for the floors on the ground level and Brazilian cherry for those above.

Weese, the daughter of the late Chicago architect Harry Weese, designed a rug for the living room sitting area made of olive green Tibetan wool with ivory silk accents-shades that complement the contemporary sofa and armchair by Cassina from Man- ifesto and the woven straw club chairs from Ligne Roset. The white marble and steel coffee table is a del Canto design, and the faint marks on it, he says, are fond memories of past revelries.

Unable to suppress his conviction that every spirit rises when yellow emerges, he introduced it in his design for the fireplace surround-a freestanding three-eighths-inch-thick section of sheet metal that curves like a Richard Serra sculpture. “I wanted to use the fireplace as a way to break up the rigidness of the living room,” del Canto says, “and add some color and sensuality to it.”

Recessed shelves on either side hold his collections of pre-Columbian sculptures and late 19th- and early 20th-century silver serving urns. Above the fireplace, 12 Malaysian masks are arranged in a grid. The photographs and paintings in the room are among those by Latin American artists that del Canto has collected over the years-Nereyda García-Ferraz, Sebastiano Salgado, and Ana Mendieta.

|

| In the living room, Malaysian masks are arranged in a grid over the curved-steel fireplace surround, a design by the architect. The other artwork (clockwise from left) is by Ismael Frigerio (two portraits in a series of 12), Nereyda García-Ferraz, and (opposite) Sebastiano Salgado, Sergio Larraín (top), Luis Poirot (bottom), and Ana Mendieta. |

Family photographs are displayed between stacks of art books on low, asymmetrically placed shelves of wenge wood. “In the same way that the fireplace is counter to what is typical, meaning it isn’t heavy, the bookends are the books themselves,” del Canto says. “These are little twists on the typical symbols of the status quo living room.”

A culinary wizard who used to indulge in 24- to 36-hour cooking marathons with friends, del Canto is even more philosophical about his kitchen and dining area. “The sensuality of preparing food is lost unless it is directly connected to the sensuality of eating,” he says. “There should be a continuum. And I have the room open because of that.” A fan of his brother’s cooking, Gonzalo, who designed all of the cabinetry in the house, gave Rodrigo ample space for collaborations-the granite-topped island and counter are both 14 feet long. Gonzalo varied the look of the quartersawn cherry cabinets with doors in wood, glass, and matte lacquer, and the interiors are custom designed for total access.

For a more primal cooking experience, Rodrigo had a hook installed in the kitchen fireplace-a perfect place to prepare a stew, he says. He can watch his pot simmer while sitting on a pew that he bought decades ago from a French Huguenot church in Charleston, South Carolina. (In the racks on the back, however, hymnals have been replaced by copies of Wine Connoisseur and Cigar Aficionado.)

Del Canto’s granite-topped dining table is equipped with a steel base mounted on wheels; 30 years ago, he explains, this design was more likely to be found in a morgue.

“That’s appetizing,” I say.

“It’s part of the process of living,” del Canto insists. “Life and death and everything in between is nothing but food.”

|

|

In the dining area are works by Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons and Roser Bru. |

The stamped-wood chairs that surround the table are by Thonet; those nearby of a similar design are from a Czechoslovakian manufacturer. Dispensing with formality, it seems, does not mean abandoning the accouterments of civility. Even at casual dinners, del Canto’s French and English silver candlesticks appear in multiples, and his silver napkin rings encircle the linens.

Blessing this scene from on high are sculptures from Mexican churches-a pair of angels beaming from a vivid yellow niche, four tall wise men presiding from the top of the cabinets. On the wall behind the table is a self-portrait by the Cuban photographer Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons. Inscribed to del Canto, the work next to it, by the Chilean painter Roser Bru, explores the relationship between the Inquisition, the rise of the Nazis, and the fall of Kosovo.

Culinary debates aside, politics is a major subject of discussion at most of del Canto’s gatherings. When the weather complies, one of his three decks might be the destination of the assembled crowd-to the east, there is a bright-lights, urban-drama perspective of the North Michigan Avenue skyline. Facing west, the other decks offer a grittier, more intimate back-porch look at city life. “Rear Window,” del Canto says, invoking Alfred Hitchcock. “It shows you the private lives of people. You see their kitchens, their eating areas-it’s a connection to reality.”

|

| In the kitchen, to accommodate multiple cooks, both the granite-topped counter and the island are 14 feet long. The angels in the yellow niche are from a Mexican church. |

His world goes round and round. The traffic-stopping fantasy in silk organza that he devised for the entrance of his house encountered daunting conflicts as 2005 came to a close: unfortunately, in the contest of curtains against nature, the former lost. But del Canto and Tem Struggle, a Chicago designer of fashions and interiors, decided that once they found the right wind-resistant substance, style would indeed triumph. Early this spring, they plan to unfurl a new set of curtains made of a durable synthetic mesh-in yellow, of course. Paradise regained.

Resources

Brava Kitchens

(Gonzalo del Canto)

399 Applewood Crescent

Concord, Ontario, Canada

905-669-5871

Interior design and custom-made cabinetry.

Ligne Roset

56 East Walton Street

312-867-1207

www.ligne-roset-usa.com

The woven straw chairs.

Macondo Corp Architects & Planners

(Rodrigo del Canto, managing principal)

21 West Illinois Street

312-644-5500, extension 222

www.macondocorp.com

The architect.

Manifesto

755 North Wells Street

312-664-0733

www.manifestofurniture.com

The sofa and the chair by Cassina.

Midmac Builders

715 Pfingsten Road

Glenview

847-502-5912

The general contractor.

Schmidt Design

(Maria Schmidt)

707 Clinton Avenue

Oak Park

708-524-5404

Interior design.

Struggle Dezign Company

(Tem Struggle)

2660 West Wilcox Street

Suite 1

773-826-7165

The maker of the curtains.

Weese + Design

(Marcia Weese)

2739 West Windsor Avenue

773-866-2878

www.marciaweese.com

Interior design and the custom design of the living room rug.

Photography: William Zbaren