The son of a prominent First Amendment scholar is now fighting his own press-rights battle against the City of Chicago

|

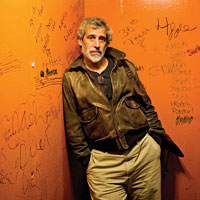

Photograph: Peter Wynn Thompson |

| Jamie Kalven's reporting and social work at Stateway Gardens have led the city to seek his notes. |

The message scrawled amid graffiti on a high-rise entryway wall advises: "Please think before you open your mouth-it could only help you in the long run."

This cautionary counsel gets heeded for the most part by gangbangers, drug dealers, and hustlers plying their trades around the concrete-block apartment building nicknamed "Trey Ball"-the last remnant of the Stateway Gardens public housing complex, on the South Side, across the Dan Ryan from the White Sox park. And even those not breaking the law around Stateway typically abide by the streetwise code of silence.

Everybody, that is, except Jamie Kalven, a self-described "human rights" reporter and community organizer. Kalven has made a name for himself as a critic of police misconduct and of the living conditions in public housing. Yet he also understands that speech has a price, and sometimes worlds can be fraught with peril.

On a recent afternoon, Kalven, 57, dropped by Stateway Gardens, wearing his standard Birkenstocks, to talk about the words that have lately led him into trouble: his account of the story of Diane Bond.

One evening three Aprils ago, Bond, a single mother then 48, returned home to her eighth-floor apartment in Trey Ball. Waiting for her at the door, according to the civil-rights lawsuit she later filed, was a coterie of plainclothes Chicago police officers notoriously known among Stateway residents as the "Skullcap Crew" because they often wore knit watch caps. The Skullcaps, all of whom are white, are members of the gang tactical unit and have fixtures for years at the ramshackle building where Bond and 50 or so other poor black families live. Bond says the officers accused her of hiding drugs in her apartment. One of the officers, she alleges, then pressed a gun against her head, seized her keys, and forced her inside the apartment. Next, she claims, she was handcuffed, as the officers beat up her 19-year-old son, Willie, and a friend who had come over to play video games. When Bond protested, she asserts, an officer slapped her face and kicked her in the ribs. After that, Bond says, the officers threatened to plant bags of drugs on her and arrest her on false charges, then forced her to expose her genitals, and coerced her son and his friend to beat up another man who also lived in the complex-as the officers watched, tauntingly.

This incident-and subsequent tales of alleged abuse-went unreported by the mainstream media, even after Bond sued the officers, the police department, and the city in April 2004. Only Kalven reported on Bond's story. Beginning in July 2005, he wrote a series of 17 articles on police misconduct in public housing titled "Kicking the Pigeon," and then self-published them on his little known Webzine, The View from the Ground.

The officers flatly deny ever having had such encounters with Bond, and investigation by the police department's Office of Professional Standards found no evidence of wrongdoing.

On June 13, 2005, the office of the city's corporation counsel, which is defending the Skullcap Crew in the lawsuit, subpoenaed Kalven, seeking his interview notes, tapes, drafts of articles, and other records he had gathered concerning police conduct at Stateway Gardens.

Kalven has refused to surrender any materials, citing First Amendment protections shielding journalists from government interference in gathering news. The city continues to press. "He's cited reporter's privilege-we dispute that that actually exists," says Jennifer Hoyle, the spokeswoman for the city's law department. Even if it did, she adds, "he's gone beyond being just a journalist in the case; he's become a witness and participant in the investigation." And now the city has asked the assigned judge, Joan H. Lefkow, to hold Kalven in contempt of court-a charge that could mean substantial fines and even jail time.

[Editor's note: Just before Chicago went to press, Magistrate Judge Arlander Keys denied the city's petition to compel Kalven to give up his notes and other reporter's materials. Keys ruled that the subpoena was overbroad and that it placed an undue burden on Kalven as a journalist, jeopardizing his ongoing reporting at Stateway Gardens. However, the ruling did not specifically address the broader questions of journalistic privilege and First Amendment law.]

Kalven says he is not looking for a First Amendment showdown; he claims that he is simply trying to call attention to abusive policing in public housing. But the saga provides, perhaps, an appropriate twist of fate for him. His father Harry Kalven Jr., was a renowned First Amendment authority at the University of Chicago who once defended the comedian Lenny Bruce and taught torts to John Ashcroft, U.S. attorney general during President George W. Bush's first term. In 1974, when Harry Kalven died of a heart attack, at 60, he was working on a first draft of an exhaustive book on free speech and civil liberties. It was to be his masterpiece. Jamie, the oldest of four children, felt that his father's unfinished work was too important to go unpublished. Then 26, Kalven put his fledgling freelance-writing career on hold and spent the next 14 years turning the 1,000-page manuscript into a finished title, A Worthy Tradition: Freedom of Speech in America.

When it was finally published in 1988, the 600-page-plus tome won plaudits; reviewing it for The New York Times, Benno C. Schmidt Jr., then president of Yale, singled out the son's labors as "an extraordinary act of intellectual and filial devotion."

Now, 32 years after his father's death, the world of First Amendment law has tugged on Kalven again. His story-part bildungsroman, part legal drama-showcases the uneasy balance between First Amendment traditions and the government's powers, and it comes at a time when the legal status of reporters in notable unsettled.

Of course, there were the travails last year of Judith Miller, the former New York Times reporter who spent 85 days in jail for refusing to reveal sources to a grand jury investigating the leak of CIA officer Valerie Plame Wilson's identity. Miller's case arose at a time when several reporters around the country were also involved in high-profile court battles because of their refusal to reveal confidential sources. The latest showdown happened in May, when a federal prosecutor issued grand jury subpoenas to two San Francisco Chronicle reporters who covered the ongoing investigation into the Bay Area Laboratory Cooperative, or Balco, which allegedly had distributed steroids to Barry Bonds, among other professional athletes.

Geoffrey R. Stone, a law professor at the University of Chicago, and the author of Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime, says the courts are increasingly reluctant to grant the media any special protections. "For the most part, governments have not wanted to take on journalists because it's bad publicity," says Stone. "But for the last several years we've seen the government more aggressive about picking that fight."

The idea that the First Amendment affords journalists a "privilege"-the right to refuse to divulge sources and other newsgathering details-is murky at best. The supposed privilege stems from Branzburg v. Hayes, the landmark 1972 U.S. Supreme Court case in which the Court, on a 5-4 vote, rejected First Amendment protection for reporters facing grand jury subpoenas. While the majority opinion was a scathing rebuke of the journalists' position, reporter's privilege advocates have argued since then that newsgathering deserves at least some protection, a suggestion offered by Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. in his concurring opinion in Branzburg and supported by the four dissenting justices. Because the five justices supported First Amendment protection, the advocates argue, reporter's privilege should exist. Unfortunately, for these advocates, only the majority opinion, which finds no reporter's privilege in the First Amendment, carries legal weight.

Adding fuel to the fire for supporters of reporter's privilege are state laws and court decisions protecting reporters from being compelled to reveal confidential sources, on the books in all the states except Wyoming. These laws, however, do not protect reporters subpoenaed in cases prosecuted in the federal court system, such as the case involving Kalven.

The legal tide against journalists really began to swell in 2003, after a prominent federal appeals court judge in Chicago, Richard A. Posner, in a case involving a Sun Times reporter, disavowed the existence of any constitutional right to protect confidential sources. The case opened the floodgates to other First Amendment confrontations. (Consistent with the chain of coincidences in this story, Posner was a colleague of Harry Kalven's at the U. of C.)

Jamie Kalven clearly recognizes that the law has been turning against journalists. But he argues that surrendering his confidential research and working materials would jeopardize his reporting. Many of the people he writes about are a part of the network that he has built over many years at Stateway. "For me," he says, "these are friends, colleagues, neighbors." He continues: "If I turn my papers, and thereby become a de facto agent of a hostile state investigation, it would severely damage my ability to report on important public issues-to do the sort of reporting that I do. People wouldn't tell me things knowing that I could be forced against my will to give up the information."

But Kalven's fierce defense of free speech rights is also intensely meaningful and personal. The thought of turning over his papers, he says, is horrifying, "as visceral as being poked in the eye." Especially since he has a family legacy to uphold. "In some ways," he says, complying with the subpoena "would nullify what my life and work have been about."

|

Photos: Courtesy of the Kalven Family |

| Jamie, pictured here as an infant taking flying lessons, followed in the footsteps of his father, Harry Kalven Jr., organizing and editing Harry's First Amendment book after his death. |

|

Harry Kalven died at this desk, working on his book. Jamie Kalven remembers that ill-fated day, the one when-as he puts it-he "came back home and took over the family farm." He was living in San Francisco at the time with his wife, Patricia Evans, a photographer, and had just begun his career as a freelance writer, having given up on other pursuits, like climbing mountains on far-flung continents.

Kalven immediately returned to Chicago, to his parents' Tudor revival home on Woodlawn Avenue in Kenwood. Up in his father's third-floor study, the unfinished manuscript-the culmination of five years work and decades more of scholarship-lay spread across the floor in a series of binders, along with heaps of other papers, notes, briefs, and news papers clippings. "My first thought upon learning of my dad's death was, Who will I talk to now?" says Kalven. And being in the study that day, seeing his father's life's work incomplete, his next thought, he says, was, "Who's going to finish the book?"

He brooded over the question for months, and with his family's blessing, he took it upon himself to carry on his father's work. Though not a lawyer, Kalven immersed himself in all things First Amendment. With the help of Owen M. Fiss, one of his father's former colleagues at the U. of C. (now at Yale), Kalven painstakingly deciphered the massive manuscript-and intricate puzzle with 600 notes in the margins and annotations, 800 pages of handwritten notes outlining 300 court cases, and 400 or so odds-and-ends pages. He also studied his father's other published writings and even sought out some former students to comb through their class lecture notes. And like a forensic investigator, he pieced together his father's last words.

Fiss recalls Kalven's unwavering dedication to the task, despite, he says, the "tremendous psychological weight" it carried. "I think it did put strains on him," he says. "But there were not moments of ‘I give up,' ‘I can't do this.' The metaphor of mountain climbing comes to me. He was a climber, and this was a climb. And very few climbers turn back."

To help support himself over the 14 years it took to finish the project, Kalven relied on foundations grants, freelance writing fees, and weekend work as a general handyman. "When I finally finished the book, a lot of people were really concerned that I would have all sorts of postpartum depression," says Kalven. "I didn't have any of that." Rather, he adds, working on the book was a labor of love that deepened his commitment to his father's great passion: the First Amendment.

Even so, he adds that he did not want the book to typecast him for life as a First Amendment writer. "I didn't want to be the public voice coming to the defense of First Amendment principals," he says. "I believe in ultimately defending the First Amendment by exercising it."

One violent day in the fall of 1988 led Kalven eventually to Stateway Gardens. The date was September 21st-the afternoon Patricia, his wife, was brutally beaten and sexually assaulted in broad daylight while jogging on the lakefront near their Hyde Park home. In the attack's aftermath, Kalven set out to learn from his wife's trauma and, perhaps, comprehend the deeper roots of poverty, violence, and America's racial divide (Evans's attacker was black; she is white). He accomplished this partly by writing a gut-wrenching memoir, Working with Available Light: A Family's World After Violence, and also by becoming a community organizer at Stateway-one of the poorest and most violent areas of the city.

Kalven set up an office in a vacant first-floor apartment in the now demolished high-rise known around Stateway as the "House of Pain," and he because a regular presence in the sprawling network of buildings. He organized projects to transform gritty vacant lots into public gardens, parks, and playgrounds, and to help ex-offenders and gang members get jobs. In time, he became an adviser to the Stateway Gardens residents' council, befriending a spectrum of people, he says, including "sociopaths and some of the loveliest human beings I know." Likewise, he also witnessed the demolition of Stateway Gardens as part of the Chicago Housing Authority's so-called Plan for Transformation, a ten-year strategy to tear down blighted, crime-ridden high-rises, replacing thousands of units with a mixture of new public housing apartments, condos, and pricey town homes.

Not long after arriving at Stateway, Kalven began collecting stories of suspected abuses against residents by the Skullcaps. He spent several years investigating these incidents-interviewing victims and witnesses, assessing the accuracy of their stories, and examining the police department's monitoring and disciplinary policies and practices. Unsatisfied with how the police handled his complaints, he took matters into his own hands: persuading Craig Futterman, of the U. of C.'s Mandel Legal Aid Clinic, to represent Diane Bond in her lawsuit. In fact, the clinic filed five other civil-rights lawsuits stemming from alleged police abuses at Stateway; all but Bond's and one other case have been settled. The most recent was a $499,000 class-action lawsuit filed in 2001 involving about 250 Stateway residents who claimed that police had illegally searched them during a basketball tournament.

Frustrated by the lack of attention given to the conditions of public housing, particularly to the police conduct there, Kalven began publishing The View in 2001 as a Webzine, reporting, he says, "from a committed and engaged and embedded perspective, and never disguising that." To his critics, however, Kalven is an activist masquerading as a journalist. He freely admits that his dual role as a Stateway insider and "objective" investigative reporter is complicated, and he knows that he walks a very fine line. But he says that it's wrong to "assume that if you're not doing on-one-hand, on-the-other-hand kind of journalism that you can't be rigorous." He continues: "I was a writer when I first went to Stateway-I've been a writer throughout my involvement there. It's possible to be both a witness in the case and continue to function as a journalist, with all the requisite protections under the First Amendment."

But Jennifer Hoyle, the law department spokeswoman, says Kalven is too personally involved in the case to be granted special privileges or immunities. "He had had extensive contact with the plaintiff in the case and he's worked with the plaintiff's attorney," she says, referring to Bond and Futterman. "He's taken himself out of the position of simply being an objective observer and, at this point, he's a witness in the case. And as a witness, we are entitled to take the same discovery that we would [with] any other witness."

Futterman calls the subpoena a "fishing expedition," and argues that the city's actions against Kalven amount at least to legal overkill, if not suggesting "a certain whiff of retaliation." "It's not just any reporter," he says. "They've targeted a reporter who has exposed government abuses."

Indeed, this case does raise the question: Is it coincidental that Kalven in the only journalist in recent memory to have been subpoenaed by the city? (The law department does not keep records on how many subpoenas it has issued to journalists, but Hoyle admits that the city has never taken a reporter's privilege case as far as Kalven's.)

Kalven has an idiosyncratic view of his legal predicament. "What the city is doing now-I'm not without sympathy for it," he says. "Certainly, if I were on trial for a serious crime and somebody was in a position of having evidence that could bear on my defense, I would want to have access to it, too."

But he maintains that he had cooperated-for the most part-with all of the attorneys involved in the lawsuit. In April he gave a deposition, refusing only to answer questions unrelated to the Bond's complaint. He says today that he is not protecting anonymous sources; all the sources referred to in his writings either are included already on the witness list or can be found through other means. "It seems to me that there are major First Amendment consequences-in order to achieve a mysterious and, at best, a pretty attenuated state of interest."

Kalven speculates that the city's true aim in subpoenaing him is to keep his public scrutiny of the police under wraps and shut down his efforts to expose human rights abuses committed by some problem officers-a point, he says, that is overshadowed by the First Amendment confrontation. "I think we often think it's just a matter of, Will you be found in contempt, or not? Will you go to jail?" says Kalven. "People overdramatize heroism of taking these steps. What the real cost is, which you're going around being a hero, it displaces your real work."

In October, Diane Bond's case is scheduled to go to trial-the same month that she and the other Stateway families are supposed to be evicted and relocated. If the judge rules (separately) to hold Kalven in contempt of court, it is not clear what sanctions he would receive. He could be forced to choose between giving up his reporting materials and going to jail. Short of imprisonment (which, in all likelihood, would last only the duration of the Bond case), Kalven could be fined. But unlike Judith Miller of The Times, Kalven does not have the backing of a newspaper conglomerate; he says he would have to empty the family's coffers to pay the legal bills.

Of course, the judge could always quash the city's subpoena, but even Kalven is skeptical that will happen, given the way the courts have leaned against journalists lately. A friend of Kalven's father, former U.S. attorney Thomas P. Sullivan, now a partner at Jenner & Block, has taken on Kalven's case pro bono.

These days, Kalven lives only a few blocks away from his family's old home on Woodlawn, and he often walks by the 97-year-old Tudor. With salt-and-pepper hair now covering his head and pronounced bags under his eyes, Kalven seems far removed from the days when he was a grieving son grappling with completing his father's work. And that book, he says, now seems "like a time capsule." But even so, Kalven's connection with his father persists and is perhaps stronger than ever. "It's kind of amazing," he says, "to see it now as sort of a prelude to this other drama that's now unfolding."

Comments are closed.