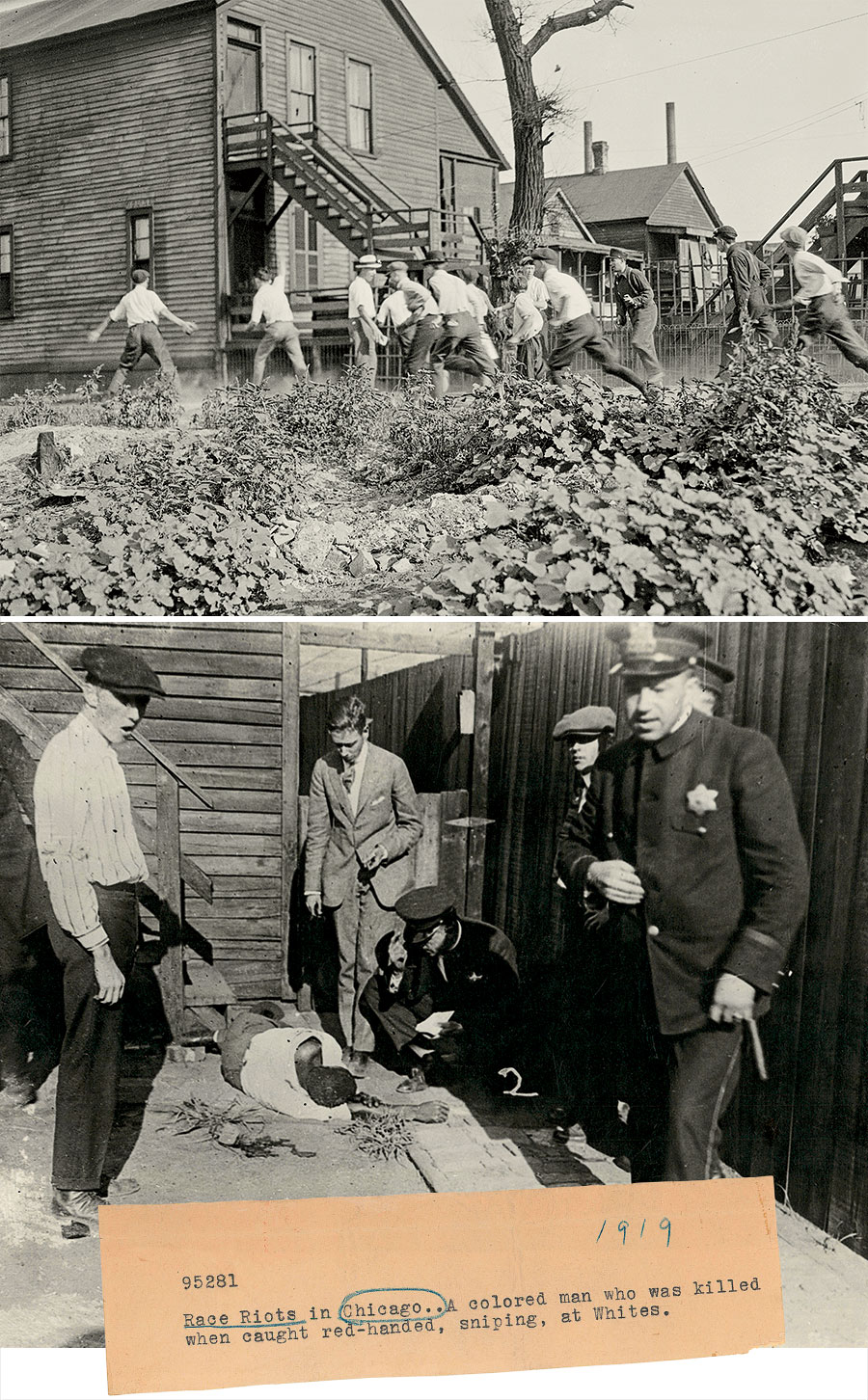

For nearly a week in the summer of 1919, Chicago descended into “a certain madness,” in the words of the city’s leading black newspaper, the Chicago Defender. White mobs assaulted virtually any black person they could find on the streets, and blacks engaged in deadly acts of retaliation and self-defense. By the time the violence subsided, 38 men — 23 of them black and 15 white — had been killed and more than 500 people were injured. “Chicago is disgraced and dishonored,” the Chicago Daily Tribune declared. “Its head is bloodied and bowed, bloodied by crime and bowed in shame. Its reputation is besmirched. It will take a long time to remove the stain.”

Jolting Chicago during the early years of the Great Migration, the riot cast a shadow over race relations in the city for decades. A hundred years later, it remains the worst outbreak of racially motivated violence in Chicago’s history — and one of the deadliest nationally.

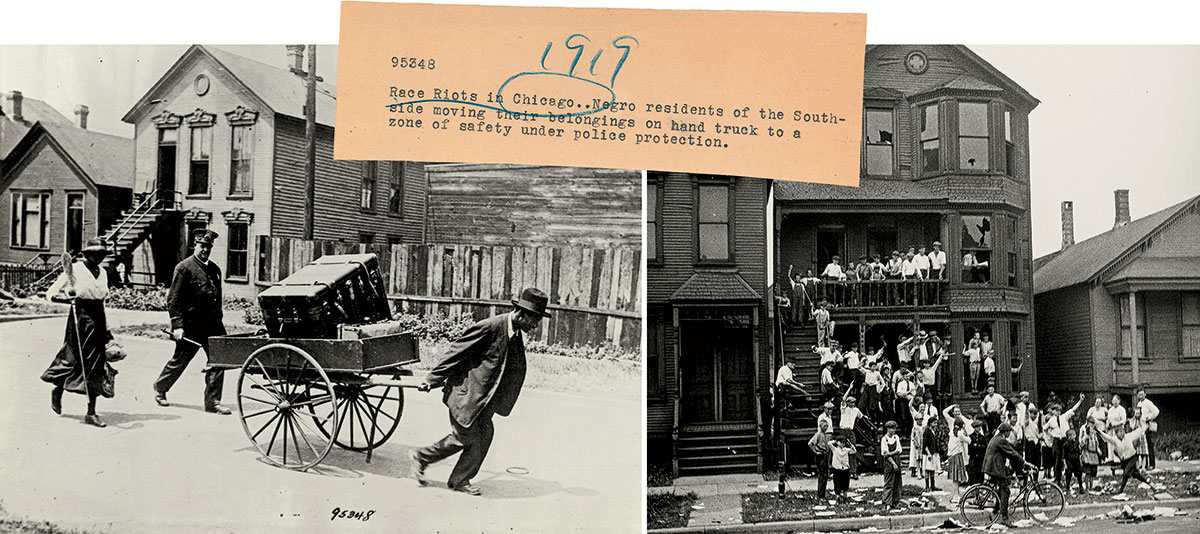

At the time of the riot, the composition of the city was changing, fueling tensions. From 1910 to 1920, Chicago’s black population grew from about 44,000 to nearly 110,000 — still just 4 percent of the city’s 2.7 million residents — as Southern blacks moved north to flee Jim Crow laws. Previously, most black Chicagoans lived in an area called the Black Belt, from 22nd Street (now Cermak Road) south to 39th Street (now Pershing Road) and from Wentworth Avenue east to State Street. Now they were starting to move into bordering neighborhoods. “Their presence here is intolerable,” the Kenwood and Hyde Park Property Owners’ Association said in its March 1919 publication. “Every colored man who moves into Hyde Park knows that he is damaging his white neighbor’s property.” Meanwhile, white men returning to Chicago after fighting in World War I found themselves working alongside and competing with black men for jobs in the stockyards and meatpacking plants.

In the two years leading up to the riot, bombs were thrown at two dozen homes of black Chicagoans. The police solved none of these crimes. A 6-year-old girl named Garnetta Ellis died in one explosion. And early in the summer of 1919, several attacks on blacks by white mobs were reported on the South Side. “It looks very much like Chicago is trying to rival the South in its race hatred against the Negro,” the renowned black journalist Ida B. Wells wrote in a letter published by the Tribune on July 7, 1919. “Will no action be taken to prevent these lawbreakers until further disaster has occurred?”

Twenty days later, her words would prove prophetic.

This is the story of the 1919 race riot as told by eyewitnesses. Their words are drawn from official reports, newspaper articles of the time, court records, and historical archives. Several of these passages have never before been published.

Some quotes have been lightly edited for conciseness and clarity. Offensive language has been left in to reflect sentiments of the time.

Sunday, July 27

“Oh my God!”

It was the hottest weekend of the year, with temperatures hitting 95. Chicagoans crowded the beaches, many of them seeking to cool off in Lake Michigan. That afternoon, a black 15-year-old South Sider named John Turner Harris headed for the lake with four of his friends, catching a ride on the back of a produce truck.

Harris(in the unpublished transcript of his interview for William M. Tuttle Jr.’s 1970 book Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919): We got off on 26th Street and went to the 25th Street beach. This is where most of the Negroes went. Now, on 29th Street, the white people formed the little beach right behind Michael Reese Hospital. The funny thing is, I didn’t question it. If you don’t want to be bothered with me, I don’t want to be bothered with you. They had their little beach. And they were welcome to come over to ours anytime they wished — and they did, when they wanted some seclusion. We were not allowed over there, because there was always a fight. Nothing I wanted was over there anyway. So we added a colored lifeguard and a colored policeman [to the 25th Street beach].

We were in this little area right in back of the Keeley Brewing Co. and the Consumers ice company. We called it “hot and cold,” because in cleaning out the beer vats, naturally the water was cold. But this water had lime and stuff in it, and it was hot — and Jesus, I would be as white as you when I got done. No women or nothing ever come through, so we didn’t even wear a suit — just take our clothes off and go down on the bank. We’d go up on this little island, then we would put in our little raft. Four different groups of about 20 boys worked on this raft for about two months. It was a nice size — about 14 by 9 feet. Oh, it was a tremendous thing. And we had a big chain with a hook on one of the big logs, and we’d put a rope through that and tie it.

We were pushing this raft in the water, not getting too far. None of us were accomplished swimmers, but we could dive underwater and come up. We would push the raft and swim, kick, dive, and play around. As long as the raft was there, we were safe.

Chester Wilkins,a black 25-year-old Mississippi native who lived on the South Side (in an interview for Tuttle’s book): There had been bad feelings over there, especially in that swimming area. They wanted to bar the Negroes from going swimming in the lake at all. Kids would always have to collect a group of kids, because if you went individually and run into a couple of white kids, you would end up with a bloody nose.

Chicago Evening Post:The trouble started, it is said, when two Negro couples appeared on what is called the “white section” of the improvised 29th Street beach and demanded the right to enter the water there. When refused, according to whites, they became abusive and threatened to return soon with a crowd of their friends and “clean up the place.”

Chicago Commission on Race Relations(in its report on the riot): It was not long before the Negroes were back, coming from the north with others of their race. Then began a series of attacks and retreats, counterattacks, and stone throwing. Women and children who could not escape hid behind debris and rocks. The stone throwing continued, first one side gaining the advantage, then the other.

Around 3 or 4 p.m., Harris and his friends pushed their raft southeast, passing a breakwater that jutted into the lake at 26th Street and nearing the white area. One of the boys was Eugene Williams, a black 17-year-old Georgia native who worked as a grocery porter.

Harris:This Polish fellow was walking along the breakwater. It had to be between 75 and 100 feet from us. We were watching him. He’d take a rock and throw it, and we would duck. As long as we could see him, he never could hit us — because, after all, a guy throwing that far is not a likely shot. One fellow would say, “Look out, here comes one,” and we would duck. It was just like a little game. This went on for a long time.

Eugene had just come up and went to dive again when somebody averted his attention. And just as he turned his head, this fellow threw a rock and it struck him on the right side of his forehead. I had just come up, and I could see something was wrong. He didn’t dive — he just sort of relaxed.

I went under with him and saw the blood from his head. He grabbed my right ankle. And hell, I got scared. I shook him off. We were in about 15 feet of water at the time, and I had gone down about 10 feet with him. You could see the blood coming up.

The fellows were all excited and didn’t know what to do. And the fellow, when he done it, seemed to say something — sounded like: “Oh my God!” The boys watched as he ran back to the confines of this pile of rock right back of Michael Reese.

The Cook County coroner’s jury, impaneled routinely at the time to decide whether a death required a criminal investigation, had a slightly different version of the event.

Coroner’s jury(in its report): We find that Eugene Williams was in the water clinging to a railroad tie, that numerous stones were thrown by the white men in his direction, preventing him, from fear of bodily injury, from landing, being compelled to remain out in the deep water of the lake until he released his hold on the railroad tie and drowned.

Peter M. Hoffman,Cook County coroner (in the Tribune): There may have been stones thrown at him, but none hit him, or there would have been a hemorrhage under the skin.

Harris:I said, “Let’s get the lifeguard.” So I got a breath and swam underwater till I got to the island, then I got up and ran over to the beach, which is a good block away. I told the head lifeguard — Butch, they called him — and he blew a whistle and sent a boat around. He ran along with me and dove in and went to the raft. The boys were still on it. They were panic-stricken, but they kept their eye on this fellow [who threw the rocks]. This colored cop walked along the shore with me. We pointed the fellow out. He was nervous.

So the colored cop went to arrest him, and the white cop would not let him arrest him. There was a big argument between the two policemen. We ran back to the 25th Street beach and told the colored people.

In the meantime, the lifeguard had gotten the boy’s body, and naturally all the people were here on this island. Then they came over and demanded that they arrest the man. And this is when the fight started. If the police had been on the ball, nothing would have happened, but they started beating people, clubbing them.

I got out of there. Hell, I left my shoes, my hat, and everything. I cut all the way down to 26th Street, all the way down to Wabash. We were putting our clothes on as fast as we were running. Then we caught a bus.

The man accused of hurling the stones was George Stauber, a 24-year-old baker. Although Harris remembered him as Polish, Stauber was the son of a brewer who’d emigrated from Bavaria. He lived a quarter mile west of the beach in an apartment on South Cottage Grove Avenue.

Theresa Donnelly,Stauber’s daughter (in a recent letter to Chicago magazine): Our dad rarely spoke of his youth. We knew his parents were poor, lived in the South Side near the rail yards, because as a 4-year-old, he — with others — picked up the coal that fell from the passing trains in order to heat their home. His birth mother died when he was quite young, while giving birth to his brother. The infant also died. His father sent for a mail-order bride from Bavaria to raise his children. They had three daughters of their own. My father left school either at 7 or 9 years of age — we are unsure — to apprentice in a local bakery. He cared for his stepmother as she grew severely crippled with arthritis.

The white policeman who refused to arrest Stauber was Daniel Michael Callaghan, 38, who’d emigrated from Ireland. Callaghan (whose name is misspelled “Callahan” in many reports on the riot) worked out of the 3rd Precinct police station, a few blocks west of the beach. The black cop who wanted to arrest Stauber was William Middleton, a 35-year-old detective sergeant from Savannah, Georgia, who’d joined the police force in 1911.

Middleton(in the Chicago Daily News): I can produce seven witnesses to prove that this man threw the stone.

Chicago Commission on Race Relations:Reports of the drowning and of the alleged conduct of the policeman spread out into the neighborhood. A mob of about 1,000 Negroes congregated at 29th Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, whence they had chased Officer Callahan. Other policemen attempting to disperse the mob were assaulted. James Crawford, Negro, fired a revolver directly into the group of policemen. They retaliated, and Crawford ran. A Negro policeman followed Crawford, attempting to stop him by firing. Crawford was wounded and died [two days later] on July 29.

Monday, July 28

“You’ll be going to Hell’s Valley”

Lucius C. Harper,the Defender’s city editor: Excitement ran high all through the day. Groups of men whose minds were inflamed by rumors of brutal attacks on men, women, and children crowded the public thoroughfares in the South Side district from 27th to 39th Streets, some voicing sinister sentiments, others gesticulating, and the remainder making their way home to grease up the old family revolver.

Added to the already irritable feeling was the fact that some whites had planned to make a visit to the South Side homes with guns and torches. This message was conveyed to a group of men who were congregated near 36th Street, on State.

I elbowed my way to the center of the maddened throng as a man — with his face covered with court plaster — recited the story of his experience at the hands of a mob, which had pounced upon him unannounced at 31st Street and Archer Avenue.

Around 4:30 p.m., a 64-year-old fruit merchant named Casimiro Lazzaroni, who’d come to America from Italy in the 1880s, was stabbed to death on State Street, just south of 36th Street. An hour later on the same block, a 31-year-old white Chicago native named Eugene Temple was stabbed to death as he walked out of the laundry he owned. Authorities said the assailants in both slayings were black.

Samuel T.A. Loftis,an Irish American diamond merchant (in the Tribune): I had just arrived in the city from a business trip. I heard about the trouble, and thought — because I was a friend of Mayor [William] Thompson and acquainted with many leading Negroes — I could help assuage the race feeling. I got in my car and told the chauffeur to drive south on State Street. At 29th a colored mob was wrecking a pawnshop. I stopped to remonstrate. They fired seven shots at me from a distance of 10 feet. Still, I thought I could get them to listen to me and I halted, but there were eight more bullets whizzing my way. Nearly all hit the auto. At 31st and State Streets about 100 whites were attacking a Negro and his baby. I grabbed him, shoved him into the automobile with his child, and took him to the Illinois Central Depot at 31st Street.

Julius F. Taylor,the editor and publisher of a local weekly black newspaper called the Broad Ax: It was near half past 5 o’clock when we boarded a Racine Avenue trolley headed for home. As the car turned at the corner of Root and Halsted Streets, one member of the hellhounds, standing there waiting for a colored villain, ran up and pulled the trolley, causing the car to stop at the worst and most dangerous place along the whole route. The conductor, being a husky fellow, jumped from his car and dealt him a hard jolt in the jaw.

Before the car arrived at 47th and Racine a colored man snaked out from where he had been hiding. And being rather dark, he was frightened almost to death — for no doubt, like ourselves, he felt that the judgment day had come. And as he boarded the car, the white passengers — who seemed to be real friendly — urged him to duck down on the floor between them, so that the leaders of the mob would not detect him. The car rushed around the corner at breakneck speed and made a beeline for 63rd Street.

White mobs killed four black streetcar passengers that Monday — John Mills, Henry Goodman, Louis Taylor, and B.F. Hardy — and severely beat another 30. A white 19-year-old Bridgeport resident, Nicholas Kleinmark, was stabbed to death by a black streetcar rider, allegedly while Kleinmark was leading a mob attack and wielding a club.

Lena Lenocker,a German American woman (testifying in a lawsuit): I seen a car stop right at the corner of 35th and Robey [now Damen] and I seen a man get off with a tool chest, and I saw a mob after him. And as they passed on, I seen it was Mr. Grimes, and they chased him and they hollered, “Get him! Get him! There’s a darky! Get him!” I seen him stumble — and with that I go into the house and call up for the patrol. And as I came out, why, somebody said they had killed him.

As it turned out, her neighbor James G. Grimes, a black 31-year-old Chicago native who worked at a clothing store and moonlighted as a piano tuner, survived the attack. Beaten and shot in the head, Grimes, who was married and had a 1-year-old son, was left blind.

O.W. McMichael,a member of the coroner’s jury (in its report): Ninety percent of the crowds were mere curiosity seekers. The small, vicious element, finding shelter in the excited crowds, found excuse to vent their impulses to rob and kill, then separate and hide in the crowds or slink away.

Chicago Commission on Race Relations:Often the “sightseers” and even those included in the nucleus did not know why they had taken part in crimes, the viciousness of which was not apparent to them until afterward. With minds already prepared by rumors circulating wherever crowds gathered, it was easy to arouse action. A streetcar approaching and the cry, “Get the niggers!” was enough. Counter-suggestion was not tolerated when the mob was rampant. A suggestion of clemency was shouted down with the derisive epithet, “Nigger lover!”

Edward Dean Sullivan, a journalist born in Connecticut, had arrived in the city to start a job at the Chicago Herald and Examiner just as the riot was breaking out. He went into the riot zone Monday evening, driven on a motorcycle by circulation manager Dion O’Banion, who would soon become one of Chicago’s most notorious mobsters.

Sullivan(in his 1929 book Rattling the Cup on Chicago Crime): Every window in sight contained six to eight Negro faces. At intervals of every few doorways were policemen, well back in the shelter and peering intently and defensively at the massed faces in the buildings opposite. We drove down State Street, absolutely alone, a one-motorcycle procession. In the distance we could see a vast complement of fire apparatus engaged on a great fire. In our vicinity there was not the slightest traffic in the street, and it was as quiet as though the thousands of Negroes, gazing intently at us from the surrounding windows, were merely masks.

John E. Hawkins,a black police inspector (in the Tribune): A band of Negro robbers began looting stores on South State Street. A colored policeman — Simpson, recently returned from the army — attempted to place the men under arrest, and they shot him.

Sullivan:As we reached 31st Street, I saw a policeman on his knees, feebly reaching for his hat, which rested on the ground before him. His name was John Simpson of the Wabash Avenue station, and, as I watched him, he died.

Simpson, 30, born in Kentucky, had worked as a railroad cook before joining the police force. He would be the only officer killed during the week of rioting.

Sullivan:A shot exploded at my ear, fired by my driver, who was gazing intently at a roof above the policeman. Before I even saw anything on the roof, he darted ahead and into an alley. About 20 Negroes, waving, cursing and obviously drunk, were to be seen about halfway down the alley. One, with his back toward us, fired a shot into the air. They discovered us, even as my driver turned abruptly and started back up State Street.

I took a quick glance at the building before which the policeman lay. On its roof was a Negro, his eyes on us, struggling with a giant Negress, dressed in white. He had a rifle, and was trying to turn it toward us. We veered over the curb on his side of the street and passed along north at lightning speed.

Distant guns were popping. The metal bowl of a shovel came hurtling down on the sidewalk a short distance ahead of us. We hugged the curb, jolting along at top speed. At 25th Street and State, a group of police officers and executives were gathered. We drove over to them. “There is a policeman down the street —” I started to say.

A police captain looked at me, stony-visaged. “We know all about that. Things are popping. Get that machine out of here as fast as you can.”

Seventeen-year-old Arthur G. Falls lived with his parents and eight younger siblings in the Ogden Park area of Englewood, a neighborhood that was mostly white at the time. As a freshman at Englewood High School, he’d been one of only five or six black students. Falls was now attending Crane Junior College and working downtown at the post office with his father, William.

Falls(in his unpublished manuscript “Reminiscence,” written around 1962 and archived at Marquette University): No one expected the rioting to spread to our home community. Nevertheless, the one policeman who patrolled the whole area recommended that we all go in at 6 p.m. About 8 o’clock in the evening, we suddenly began to hear shouting from both north and south and learned that we had been surrounded by mobs on 63rd and 59th Street, and more thinly on Loomis and Racine Avenues.

We learned also that the stimulating influence in these mobs seemed to be the Ragen Colts, who had roaming bands of youths looking for Negroes to beat up and to kill. Most of us recognized the fact that this meant trouble.

Ragen’s Colts, an organization of Irish American teens and young men, started as a baseball team at the turn of the century. While presiding as its boss, former star player Frank Ragen ascended in politics, becoming a Cook County commissioner. The club, meanwhile, purportedly morphed into a street gang — the biggest in Chicago. Its motto was said to be “Hit me and you hit 2,000.”

Falls:We learned that the mob intended to come through the area to “burn us out.” The colored people in the area formed patrols to man the alleys. They knocked out all the lights along Ada and Throop Streets and also 61st and 62nd Streets, and lay in wait for the mobs to come in. Most of the colored families were well armed, and numbers of them had had army experience, just having returned in the previous months. As a result, we heard that the one policeman told the mob, “If you go down there, you’ll be going to Hell’s Valley.” In my own home we had only broom handles and the iron poker from the stove to defend ourselves. My father and I stayed up all night — he at the front window and I at the rear.

Harper:Hell was yet to break loose, and by fate I was destined to be present. It occurred at Wabash Avenue and 35th Street at 8:10 o’clock.

Chicago Commission on Race Relations:Rumor had it that a white occupant of the Angelus apartment house had shot a Negro boy from a fourth-story window. Negroes besieged the building. The white tenants sought police protection, and about 100 policemen, including some mounted men, responded. The mob of about 1,500 Negroes demanded the “culprit,” but the police failed to find him after a search of the building. A flying brick hit a policeman.

Harper:Over 50 policemen, mounted and on foot, drew their revolvers and showered bullets into the crowd. The officers’ guns barked for fully 10 minutes. I immediately decided that my best move was to fall face downward to the pavement.

Four citizens fell wounded, one a woman. She voiced her distress after a bullet had pierced her left shoulder. A man of slender proportions stumbled over my body in the hurried attempt to escape, and plunged headfirst to the ground. A stream of blood gushed from a wound in the back of his neck. The bullet from an officer’s revolver had found its mark. Blood from his fatal wound trickled down the pavement until it had reached me.

The pavement about me was literally covered with splintered glass, which had been torn from a laundry window by the fusillade of shots, and several times I was tempted to brush the broken fragments from my back, where some had fallen, but I dreaded making a move. I arose reluctantly as a cop yelled: “Get up, everybody!”

Gunfire had killed three black men — Joseph Sanford, Hymes Taylor, and John Humphrey — but the coroner’s jury could not determine if the fatal shots were fired by police or people in the crowd. A block away, a black man named Edward Lee was killed by what seemed to be a police officer’s bullet as he walked into a Walgreen drugstore. The commanding officer at the scene, Captain Joseph C. Mullen, later testified that he was unaware that any shooting had even taken place. The Chicago Commission on Race Relations stated that it found his testimony hard to believe.

Monday’s violence was still not over, though. At 11:45 p.m., Louis C. Washington, an army lieutenant on a five-day leave, was walking home from an outing to a theater with his wife and four friends — all of them black. They encountered several white youths in the 500 block of East 43rd Street.

Washington(in the Chicago Commission on Race Relations report): I heard a yell: “One, two, three, four, five, six!” And then they gave a loud cheer and said, “Everybody, let’s get the niggers!” There were between four and six men. They crossed the street and got in front of us. Just before we got to Forrestville Avenue, about 20 yards, they swarmed in on us.

Washington was shot in his leg. Defending himself, he stabbed and killed Clarence Metz, a 17-year-old clerk who lived in Hyde Park. Metz’s father was a horse dealer of German Jewish heritage, and his mother was a child of Irish immigrants. Clarence and four of his friends had originally planned to see a movie that night.

Coroner’s Jury:Whether [Metz] was a participant in the riot, or was there out of sheer, boyish curiosity, we are unable to determine. We find that the group of colored people, en route to their home, were acting in an orderly and inoffensive manner, and were justified in their acts and conduct during said affray.

Altogether, 17 men were killed in the rioting on Monday.

Tuesday, July 29

“A pack of wild animals out for a kill”

Wells(in the Chicago Daily Journal): Free Chicago stands today humble before the world. She has shown that with all her resources, her splendid police force, her military reserve, her culture, and her civilization, she is weak and helpless before the mob. Notwithstanding our boasted democracy, lynch law is king.

Lawless mobs roam our streets. They kill inoffensive citizens and no notice is taken. They are Negroes — they are only Negroes — and it doesn’t matter. Houses have been bombed and lives taken in our glorious, free city, but it is only a few Negroes. They have had the nerve to move into white neighborhoods. It serves them right. Why should Chicago bother to make democracy safe for Negroes?

Race prejudice is as old as the world and so it is dismissed with a wave of the hand. A Negro wishes to bathe in the lake on a hot day as the rest of our cosmopolitan population. He is hit with a brick while in the water and drowned to make sport for the heathen because he dared come into the water where they are. Who cares? He is only a Negro, and Negroes have no rights that whites are bound to respect.

Adding to the chaos, the third day began with L and streetcar employees going on strike. As a result, more people than usual walked the streets that morning. The riot violence spread into the Loop, where white mobs killed two black men: Paul S. Hardwick, a 51-year-old Georgia native who was said to have “a splendid record” during his 12 years as a Palmer House waiter, and Mississippi native Robert Williams, 41, who worked as a janitor. Not long after that, Arthur Falls and his father made their way into the Loop en route to their post office jobs.

Falls:The streets were loaded with people walking to work; so we proceeded down Dearborn Street toward the post office, which was located at Jackson and Dearborn. Looking across the street, I became aware of the fact that we were being chased. I saw some really vicious-looking hoodlums, mostly young, unkempt — distinctly different from the mass of people who were walking to work.

I told my father about the situation, and finally we began to run, but at Van Buren and Dearborn Streets, the mob caught us. Even as they surrounded us, they still had some difficulty because of the fact that there were so many people on the street. As they started to attack us, they were yelling and shouting and hurling names at us, in the customary manner of mobs. I had been struck twice and was fighting back when I suddenly saw an opening in the circle around me.

I darted through this opening in the direction of Plymouth Court. Most of the mob started out after me, but I soon outdistanced them. Turning into Plymouth Court toward Jackson Boulevard, I found the street more or less deserted. But halfway was a young man standing in the middle of the sidewalk, legs apart and arms apart in an attempt to stop me. I ran with undiminished speed precisely toward his middle. And just as I came to him, I swerved to the left and with my right shoulder and arm hit him with all the force of this propelling body. And he went down like a tenpin.

When I arrived at the post office, I learned that a colored man had been killed at the corner where we were. And there came to me a feeling that perhaps my decision had not been a wise decision. Perhaps I should have stayed with my father. There was no possibility of my working at this point, and I simply remained with my face glued to the window waiting for him to arrive.

I could not help but feel some sense of dread that I might not see my father alive again. I recognized what it would mean to the family. But above all of this, I had a sense of wonder and unbelief that human beings could act as such savages as they were during this situation. I thought of the hate on the faces of these hoodlums who were running to attack us, and I thought that they looked exactly like a pack of wild animals out for a kill.

My father did arrive almost an hour later. He had been struck, but he had not been badly hurt. He had been surrounded by six white men who fought off the mob, and he had been brought safely to the post office by these six men. Needless to say, both my father and I were overjoyed to see each other safe.

At the end of the day we were sent home in government trucks, which were protected by armed guards. During our ride home — which made us pass many areas where there were roaming mobs of white hoodlums — we could not help but feel how much we depended on these guards and what would be our fate if the guards did not perform their duty.

My mother, of course, was overjoyed to see us. I think all of us felt a certain sense of helplessness and that we did not feel that the city police were in any way handling the situation and, quite the opposite, the police frequently not only joined the mobs but stood by and saw people beaten and killed without making any effort at all to apprehend the persons responsible. One of our neighbors had been very badly beaten the night before by a group while the police looked on.

The day’s violence was far from over, and the Broad Ax’s Julius Taylor, who lived about two blocks from Falls, knew it was headed their way.

Taylor:Hundreds of desperate or rough-looking white men could be observed rushing west from Racine Avenue and from other points to Ada and Loomis Streets. When we beheld a mob of almost 4,000 men crowding around the corners of those streets, we rushed in the house, grabbed the telephone receiver, and in a jiffy we were connected with Captain Madden at the Englewood police station. After informing him that 4,000 or 5,000 white men were marching on Ada and Loomis Streets — that they fully intended to set fire to the homes of all the colored people in that district that very night and then shoot them down like rats or mad dogs, while they were fleeing for their lives — Captain Madden shouted back that he would rush 75 policemen there at once.

Falls:The shouts began getting closer, and as I looked out the front window, I could see the mobs running in from 59th Street to 60th. They were also coming from the east, from Racine Avenue. The mob easily could have set fire to our home because we had no guns with which to stop them, and the only fighting we could do was in hand-to-hand conflict. I think my father, and perhaps my mother, were resigned to the fact that we might be killed.

Coroner’s Jury:The mob was there to do violence to the colored people. Shots were fired by members of the mob in the direction of 6030 South Ada Street, where one Samuel R. Johnson, a colored man, was walking. Johnson, fearing violence to himself and family, and in their defense, fired a rifle twice from the porch of his home, 6012 South Ada Street, and in the direction of the mob.

Falls:Mr. Johnson ran in and shortly after that I heard the crackle of six Winchesters. Two of the mob dropped, one killed immediately and one badly wounded, and the mob broke and fled. I had never seen any individuals run as fast.

Johnson’s shots killed a laborer named Berger Lincoln Odman, a 21-year-old son of Swedish immigrants who lived in Englewood. The coroner’s jury would conclude that the shooting was justified.

Officers John L. Conley and B.J. Conlon were near 31st Street that night when hundreds of men faced off across Wentworth Avenue — whites on one side, blacks on the other.

Conley(in the Herald and Examiner): They were just foaming to get each other. The Negroes were yelling, “Let ’em come!” And the whites were yelling, “We’re coming!” And Conlon and me just had to think, “No, you’re not,” and go for those whites. That was a bad minute. You see, the whites were trying to push by us and the Negroes were firing from the rear, and we had to break that rule about facing the crowd. You face the crowd. You don’t let nobody behind you.

Falls:My father and I, of course, again stayed up all night, even though we were quite weary; it was simply impossible to conceive of going to sleep with the threat of the mob’s coming in. So we would occasionally doze, and one would try to keep the other awake by checking the other off and on.

Eleven men were killed or fatally wounded on Tuesday.

Wednesday, July 30

“The time had come to call out the troops”

That morning, several white aldermen met at City Hall to discuss the events of the previous days. The Chicago Commission on Race Relations would later criticize them for spreading false rumors that helped arouse “vengeful animosity, fear, anger, and horror.”

Joseph B. McDonough,alderman for the 11th Ward (at the meeting): I saw white men and women running through the streets dragging children by their arms. Frightened white men told me a police captain had just rushed through the district crying: “For God’s sake, arm! They’re coming and we can’t hold them.” The police are powerless to cope with the situation. It has got away from them. I talked with more than 100 policemen who admitted this to me. There wasn’t a white man, woman, or child who got a wink of sleep last night or the night before, from the railroad tracks west to Halsted Street and from 22nd to 47th Street. We ought to call upon the militia. I know the Negroes have enough ammunition stored in their homes to carry on guerrilla warfare for a year. Unless something is done at once I am going to advise my people to arm themselves for self-protection.

McDonough, who’d been elected alderman in 1917, was closely linked to Bridgeport’s Hamburg Athletic Club, one of the white groups accused of riot violence. Future Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley, who’d graduated from high school in 1919, belonged to the club — and five years later, he would be elected its president. Throughout his life, Daley avoided questions about the riot.

Chicago Commission on Race Relations:Responsibility for many attacks was definitely placed by many witnesses upon the “athletic clubs,” including Ragen’s Colts, the Hamburgers, Aylwards, Our Flag, the Standard, the Sparklers, and several others.

Albert W. Pick, a 50-year-old Winnetka resident who ran a large hotel and restaurant supply company in Bridgeport, would serve as foreman of the Cook County grand jury that August, when decisions on riot-related indictments were being made.

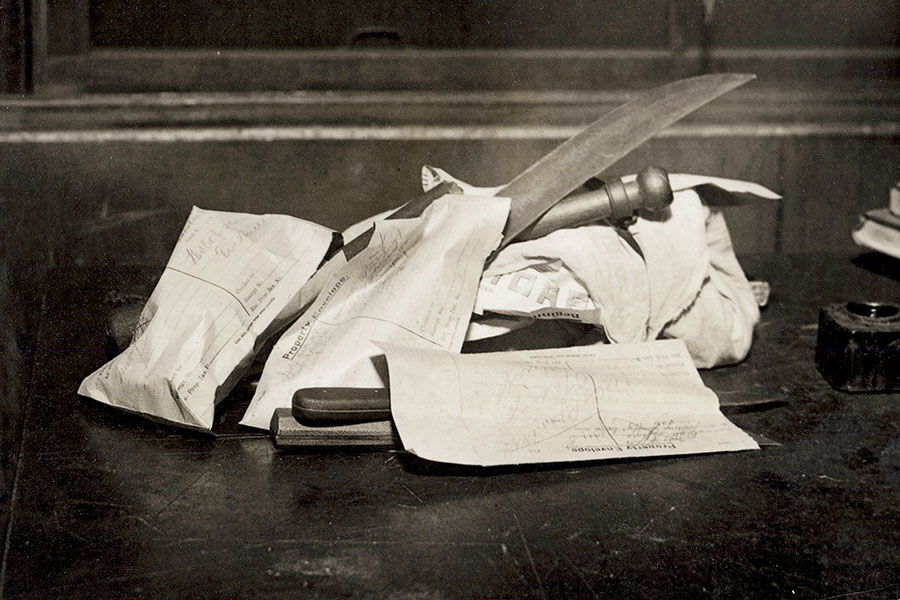

Pick(in the Chicago Commission on Race Relations report): I think they are “athletic” only with their fists and brass knuckles and guns. We learned that some of the Ragen’s Colts had broken into the police station and pried open a door of a closet, where they had a good deal of evidence — in the nature of weapons of prisoners — concealed. And they got all of this evidence out of there, without the police knowing anything about it.

Jimmie O’Brien,president of Ragen’s Colts (in the Daily News): We know our name has been linked up with the trouble in the Negro district. But I can assure you that our boys took no part in it. On the contrary, we have given street dances and entertainments in order to keep them here and to show the public that we are holding our peace. And the other night, while the riots were going on, we had thousands of people gathered at this corner who listened to our music. But we know that we have a bad reputation. Every time people here on the South Side see a band of young men, some of them perhaps drunk, they say, “Ah, Ragen’s Colts!” They try to blame everything on Ragen’s Colts.

That night, in response to reports that the homes of black Chicagoans were being set ablaze — as many as 36 during one five-hour period — Mayor William “Big Bill” Thompson requested assistance from the Illinois Reserve Militia. Three regiments had been mobilized since Monday, awaiting orders.

Thompson(in a public statement): We had information, through various sources we have developed during the riots, that there was to be a general effort to start fires. The police were worn out. In view of this condition, it was decided that the time had come to call out the troops, and I acted.

Sterling Morton, a 33-year-old Lake Forest resident whose father had founded the Morton Salt Company, was the captain of the militia’s First Infantry D Company.

Morton(in his 1959 paper “The Illinois Reserve Militia During World War I and After,” archived at the Chicago History Museum): My company, with another, was assigned the district from 45th to 51st Streets between the Rock Island and Western Indiana railway embankments. Probably a third of the houses in the district were occupied by Negroes, the balance being rather tough whites, stockyards workers for the most part.

Leading the first patrol was a rather eerie experience. The Negroes had been driven out, to take refuge east of the Rock Island tracks. For some reason the streetlights on South Wells Street were not operating. The houses were mostly old, two-story, of wooden construction. Several had been burned or were burning. The houses deserted by Negroes had been looted and in many cases Victrolas had been smashed or pulled out to the curb and burned. Every bureau drawer had been rifled and coin box telephones had been smashed to get the coins.

Generally speaking, the Negroes were orderly after the initial riots, in which they acted largely in self-defense, aggravated by very real fear of a general massacre. Our troubles were mainly caused by the young white toughs, who would dash around in cars shooting and sometimes pillaging.

Morton(in an August 11, 1919, letter to his cousin Wirt Morton): The rioters are a white-livered lot of cowards. They are all right when 20 of them jump one defenseless Negro, but when they saw the steel on the end of the rifles, they left PDQ for parts unknown, and try as we would we could not get any fight out of them.

Wednesday’s death toll reached five.

July 31 to August 8

“We always went armed”

The violence eased Thursday, with just a single killing. On Friday, no deaths and only one injury were reported. But the mayhem was not quite over. Around 3 or 4 a.m. on Saturday, fires broke out in the neighborhood west of the stockyards, burning 49 houses and leaving 948 people — mostly Lithuanian and Polish immigrants — homeless. Arson was suspected.

John R. McCabe,attorney for the Chicago Fire Department (in the Daily News): This fire is undoubtedly due to Negroes. I have at least 12 witnesses now who have told me they saw colored men in the district. Their stories tally. One man actually saw a Negro start a fire. This was Joseph Wiselewski, 4542 South Wood Street, whose home was partly burned. He said he was sitting in the front room of his house, near the window, being unable to sleep, when at 4:30 o’clock he saw a big covered automobile drive up from the north and stop in front of a hardware store at 4533 South Wood Street. He said there were between four and six men, all colored, in the car; that one of them, with a bottle in his hand, started a fire and ran back to the car. The crew then drove away.

John J. Garrity,superintendent of the Chicago Police Department (in the Daily Journal): I regret that the accusation was hurled at the colored people so quickly. I have interviewed several residents of the district and find no conclusive evidence of a plot. The story of an automobile load of Negroes racing through the streets of the burned district, carrying firebrands from the scene of one crime to another, is corroborated, as nearly as I can determine, by one witness. This man says that he was sitting in his window at 3 o’clock in the morning and that he saw an automobile half a block away, filled with Negroes. It is very dark at 3 o’clock in the morning and I doubt very much if he could have differentiated between a Negro and a white man at that distance.

Louis B. Anderson,black alderman for the 2nd Ward (in the Tribune): It is a crime to make such charges. It only serves to stir up more riots and create race prejudice. It is preposterous to think that any colored man would go west of Halsted Street without a guard of police or militia in these times. Do you think a colored man would go into this district back of the yards to set fires when 7,000 colored men have refused to go to the stockyards to get paid even though their families were starving? Impossible!

The grand jury said that white athletic clubs probably set the fires, trying to make them look like crimes perpetrated by blacks. The police believed that the culprits had blackened their faces.

Falls:By Monday, August 4, the situation was sufficiently well under control so that we could go back to work. The L and streetcar lines again were operating. However, we never traveled singly. We always went in groups of six or seven, and we always went armed. Even my father had agreed to use a knife, and I also had a knife. But some of the group with which we traveled were armed with guns.

No attempt was ever made by the police or by the militia to stop us or to search us. I think it was generally assumed that we would be armed, and since we were not giving anybody trouble, nobody bothered us. One of the things that interested me was the sign of respect with which white people dealt with us, perhaps because they also understood that we were armed. I think also that we detected a certain amount of friendliness on the part of some white people who were apparently very ashamed of what had happened and had a feeling of at least sympathy for those who had been subjected to this outburst.

Taylor:It is a pleasure to state that the white neighbors were very friendly — that many of them assisted the colored people in many ways during the disorder and rioting. Mr. and Mrs. John Sipple, our nearest white neighbors, who are highly respectable and honest, were especially kind and considerate to Mrs. Taylor. Every day and night while we were absent from home, they requested her to remain in their home — that she would receive the same protection as the members of their family, in case the rioters hoved in sight.

Many of the other white neighbors proved themselves equal to the occasion — many of them had never spoken to us before. They visited the house, both men and women, old and young, and they assured us that they were friendly to colored people, that they were willing to assist to protect those residing near unto them. And they clapped their hands with gladness every time that we arrived home safe from downtown.

On August 8, the militia was withdrawn from Chicago.

The Aftermath

“They shut their eyes to offenses”

The 15 white fatalities included five men who were apparently killed as they were committing acts of violence. Police bullets killed at least five — and possibly as many as eight — of the 23 black victims, but no officers faced any criminal charges. The racial discrepancy in the cases being brought before it was not lost on the all-white grand jury. “It is the opinion of this jury that the colored people suffered more at the hands of the white hoodlums than the white people suffered at the hands of the black hoodlums,” it said in a statement. “Notwithstanding this fact, the cases presented to this jury against the blacks far outnumber those against the white.”

The Cook County state’s attorney, Maclay Hoyne, later said: “There is no doubt that a great many police officers were grossly unfair in making arrests. They shut their eyes to offenses committed by white men while they were very vigorous in getting all the colored men they could get.”

George Stauber, the man accused of throwing rocks at Eugene Williams, was acquitted of manslaughter. He got married in 1934 and later moved to New York, where he raised three daughters. He died in 1971.

In the end, only three men were convicted of riot-related killings — all of them black and under the age of 20. Walter Covin, 16, and Charles Johnson, 18, were found guilty of killing the fruit merchant Casimiro Lazzaroni and given life sentences. Both claimed they had been beaten by police and officials from the state’s attorney’s office during interrogations and that their confessions were coerced. Reviewing the evidence a dozen years later, the state’s pardons board found that there was “great doubt” about their guilt. Both of their sentences were commuted, and the men were freed from the state penitentiary in Joliet on Christmas Eve 1933.

Some riot victims’ families, including a few white ones, sued the city, arguing it had failed to protect its people from mob violence. They were relying on a 1905 Illinois law that allowed relatives of lynching victims to sue local authorities for up to $5,000. At least 25 cases ended with the city losing — either in jury verdicts or settlements of $4,500. One of those payments went to Luella Williams, the mother of the boy who drowned.

Governor Frank Orren Lowden created the Chicago Commission on Race Relations and appointed 12 men — six white and six black — to find solutions to racial tension. For his part, the governor believed there should be a “tacit understanding” of separate residential areas, beaches, and parks for blacks and whites, leading some to believe that the commission, in the words of black state senator Warren B. Douglas, “would have for its ultimate purpose the bringing of segregation.”

But it did not take that path. “I am proud of this city, but not always proud,” commission member George Cleveland Hall, a 55-year-old black surgeon at Provident Hospital, said at one meeting. “I am not proud when I remember that the homes of 27 Negroes have been bombed and no steps have been taken to apprehend the criminals. I am not proud when I remember that not a single civic organization has taken a definite stand in protest against these outrages. The Negro is silent, but he is thinking. He cannot be expected to remain patient forever under these continued attacks.”

The commission released its findings in 1922. The 672-page report, titled The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot, detailed how blacks faced discrimination in nearly every aspect of their lives. It urged reforms at all levels of Chicago society, from City Hall, police stations, and courthouses to real estate offices, churches, and newsrooms — reforms intended to ensure that people were treated the same, regardless of skin color. The report condemned segregation as illegal and “impracticable,” warning that it would only “accentuate” racial tensions.

It all sounded well and good, but as Ida B. Wells later wrote in the autobiography she was working on at the time of her death in 1931, “many recommendations were made, but few, if any, have been carried out. Chicago has thus been left with a heritage of race prejudice which seems to increase rather than decrease.”

Arthur Falls became a physician after graduating from Northwestern University’s medical school; he died in 2000. John Turner Harris became a social worker; he died in 1979. He never returned to the spot off the 26th Street breakwater where he’d seen his friend drown.

Comments are closed.